“But your family owe me nothing. Much as I respect them, I believe, I thought only of you.”

She was silent and, after a short pause, Darcy then added, “You are too generous to trifle with me. If your feelings are still what they were last April, tell me so at once.”

The chasm of pain which this opened up, unhappily so familiar over the past few months, came vividly to his mind, and he had to pause and gather all his resolution before he could continue.

“My affections,” he paused, “and wishes are unchanged.” He stopped, and then went on, “But one word from you will silence me on this subject for ever.”

It seemed to him a very long pause, although in fact it was only a few moments, before his companion began to speak.

“Mr. Darcy, I recollect now with great distress the manner in which I replied to your offer in April....Although I was then certain that I spoke with justice and without prejudice, I have long since come to a completely contrary view. My understanding at that time of Mr. Wickham’s situation, and his own and partial account of your role in his affairs, had influenced my mind to an extent which I now consider to have been unpardonable.”

She went on quickly, “Although I then felt also that you were misguided about my sister’s feelings for Mr. Bingley, I hope that I also now have the honesty to acknowledge the difficulty for someone not very well acquainted with Jane to have been aware of them.”

She paused, and he took a quick glance at her before she continued speaking.

She had uttered the next sentence, and had begun another, before he was able to comprehend the full import of what she was saying.

“As to my own affections, it is some time since I came to realise that, far from maintaining the sentiments that I expressed in April, my future happiness depends on your having a continuing regard and affection for me. Indeed, my feelings are such that I am so very happy to accept your present assurances.”

And at last she raised her head, and met his eyes for a moment, before dropping hers again before his gaze.

They walked on, and it was some distance before Darcy had sufficient control of himself to speak.

“I find it difficult to find words which can adequately express my emotions...to be confident...to know that you return my affections,” he began.

“And our separation, since we parted in Derbyshire in July, has only served to confirm how valuable and necessary to me is your regard. That you could ever consent to be my wife has at times seemed to be so impossible that I have been close to total despair. It has been a dream which it seemed could never come true.”

He glanced at her as he continued, “And you will have to remind me very often from now on that I am not dreaming!”

He saw her smile at this, although she could not encounter his eye, and he went on to tell her how important she was to him, and for how long he had hoped for this day.

They walked on. There was so much to be thought, and felt, and said.

Darcy recounted his aunt’s visit to his house on her return through London, how Lady Catherine had related her journey to Longbourn, its motive, and the substance of her conversation with Elizabeth.

“She thought, by repeating her conversation with you, to obtain that promise from me, which you had refused to give. Some of what she told me,” said Darcy, “taught me to hope as I had scarcely ever allowed myself to hope before. One phrase in particular,

“ . . . that my wife must have such extraordinary sources of happiness necessarily attached to her situation, that she could, upon the whole, have no cause to repine?

“Words cannot express how I felt when I first heard her repeat those words, except that at last I had some hope that we might one day find happiness together.”

Darcy stole a quick glance at Elizabeth, and thought that her face was luminous with such a smile that... but he recollected himself and went on to say,

“I knew enough of your disposition to be certain, that, had you been absolutely, irrevocably, decided against me, you would have acknowledged it to Lady Catherine, frankly and openly.”

He saw that Elizabeth coloured and laughed as she replied, “Yes, you know enough of my frankness to believe me capable of that. After abusing you so abominably to your face, I could have no scruple in abusing you to all your relations.”

“What did you say of me, that I did not deserve? For, though your accusations were ill-founded, formed on mistaken premises, my behaviour to you at the time, had merited the severest reproof. It was unpardonable. I cannot think of it without abhorrence.”

“We will not quarrel for the greater share of blame annexed to that evening,” said Elizabeth. “The conduct of neither, if strictly examined, will be irreproachable; but since then, we have both, I hope, improved in civility.”

Darcy demurred at that. “I cannot be so easily reconciled to myself. The recollection of what I then said, of my conduct, my manners, my expressions during the whole of it, is now, and has been many months, inexpressibly painful to me.”

As his recollection of that evening at Hunsford returned to him, he said,

“Your reproof, so well applied, I shall never forget:

“had you behaved in a more gentleman-like manner.

“Those were your words. You know not, you can scarcely conceive, how they have tortured me. Although it was some time, I confess, before I was reasonable enough to allow their justice.”

“I was certainly very far from expecting them to make so strong an impression,” said Elizabeth. “I had not the smallest idea of their being ever felt in such a way.”

“I can easily believe it. You thought me then devoid of every proper feeling, I am sure you did. The turn of your countenance I shall never forget, as you said that I could not have addressed you in any possible way, that would induce you to accept me.”

“Oh! do not repeat what I then said. These recollections will not do at all. I assure you, that I have long been most heartily ashamed of it.”

After they had walked on a little, Darcy mentioned the letter he had written after that meeting.

“Did it,” said he, “did it soon make you think better of me? Did you, on reading it, give any credit to its contents?”

Her reply confirmed that, although in some respects it had at first angered her, over a longer period of time all her former prejudices against him had been removed.

“I knew,” said Darcy, “that what I wrote must give you pain, but it was necessary. I hope you have destroyed the letter. There was one part especially, the opening of it, which I should dread you having the power of reading again. I can remember some expressions, which might justly make you hate me.”

“The letter shall certainly be burnt, if you believe it essential to the preservation of my regard,” she replied, “but, though we have both reason to think my opinions not entirely unalterable, they are not, I hope, quite so easily changed as that implies.”

He thought for a few moments, and then said, “When I wrote that letter, I believed myself perfectly calm and cool, but I am since convinced that it was written in a dreadful bitterness of spirit.”

Elizabeth would not let him be so harsh on the author.

“The letter, perhaps, began in bitterness,” she replied, “but it did not end so. The adieu is charity itself.”

Then she went on firmly, “But think no more of the letter. The feelings of the person who wrote, and the person who received it, are now so widely different from what they were then, that every unpleasant circumstance attending it, ought to be forgotten. You must learn some of my philosophy. Think only of the past as its remembrance gives you pleasure.”

“I cannot give you credit for any philosophy of the kind,” said Darcy.

“Our retrospections must be so totally void of reproach, that the contentment arising from them, is not of philosophy, but what is much better, of ignorance. But with me, it is not so. Painful recollections will intrude, which cannot, which ought not to be repelled. I have been a selfish being all my life, in practice, though not in principle. As a child I was taught what was right, but I was not taught to correct my temper. I was given good principles, but left to follow them in pride and conceit.

“Unfortunately an only son, for many years an only child, I was spoilt by my parents, who though good themselves, my father particularly, all that was benevolent and amiable, allowed, encouraged, almost taught me to be selfish and overbearing, to care for none beyond my own family circle, to think meanly of all the rest of the world, to wish at least to think meanly of their sense and worth compared with my own.

“Such I was, from eight to eight and twenty; and such I might still have been but for you,” turning to her as he said, “dearest, loveliest Elizabeth! What do I not owe you! You taught me a lesson, hard indeed at first, but most advantageous. By you, I was properly humbled. I came to you without a doubt of my reception. You showed me how insufficient were all my pretensions to please a woman worthy of being pleased.”

“Had you then persuaded yourself that I should?” she asked him with surprise.

“Indeed I had. What will you think of my vanity? I believed you to be wishing, expecting my addresses.”

“My manners must have been in fault, but not intentionally I assure you. I never meant to deceive you, but my spirits might often lead me wrong. How you must have hated me after that evening?”

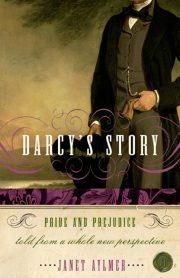

"Darcy’s Story" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Darcy’s Story". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Darcy’s Story" друзьям в соцсетях.