Pamela frowned a little. "The thing is, Jess," she said, "even though, as you say, you no longer have, um, any psychic powers, I have heard … well, I've heard missing kids across the country are still sort of, um, turning up. A lot more kids than ever turned up before … well, before your little weather-related accident. And thanks to some"—she cleared her throat—"anonymous tips."

My winning smile didn't waver.

"If that's true," I said, "it sure isn't because of me. No, ma'am. I am officially retired from the kid-finding business."

Pamela didn't exactly look relieved. She looked sort of like someone who wanted—really, really wanted—to believe something, but didn't think she should. Kind of like a kid whose friends had told her Santa Claus doesn't exist, but whose parents were still trying to maintain the myth.

Still, what could she do? She couldn't sit there and call me a liar to my face. What proof did she have?

Plenty, as it turned out. She just didn't know it.

"Well," she said. Her smile was as stiff as the Welcome to Camp Wawasee sign had been, in the places it hadn't been eaten away. "All right, then. I guess … I guess that's that."

I got up to go, feeling a little shaky. Well, you would have felt shaky, too, if you'd have come as close as I had to spending the rest of the summer stirring steaming platters of rigatoni bolognese.

"Oh," Pamela said, as if remembering something. "I almost forgot. You're friends with Ruth Abramowitz, aren't you? This came for her the other day. It didn't fit into her mailbox. Could you hand it to her? I saw you sitting with her at dinner just now. . . ."

Pamela took a large padded envelope out from behind her desk and handed it to me. I stood there, looking down at it, my throat dry.

"Urn," I said. "Sure. Sure, I'll give it to her."

My voice sounded unusually hoarse. Well, and why not? Pamela didn't know it, of course, but what she'd just given me—its contents, anyway—could prove that every single thing I'd just told her was an out-and-out lie.

"Thanks," Pamela said with a tired smile. "Things have just been so hectic …"

The corners of my mouth started to ache on account of how hard I was still smiling, pretending like I wasn't upset or anything. I should, I knew, have taken that envelope and run. That's what I should have done. But something made me stay and go, still in that hoarse voice, "Can I ask you a question, Pamela?"

She looked surprised. "Of course you can, Jess."

I cleared my throat, and kept my gaze on the strong, loopy handwriting on the front of the envelope. "Who told you?"

Pamela knit her eyebrows. "Told me what?"

"You know. About'me being the lightning girl." I looked up at her. "And that stuff about how kids are still being found, even though I'm retired."

Pamela didn't answer right away. But that was okay. I knew. And I hadn't needed any psychic powers to tell me, either. Karen Sue Hanky was dead meat.

It was right then there was a knock on Pamela's office door. She yelled, "Come in," looking way relieved at the interruption.

This old guy stuck his head in. I recognized him. He was Dr. Alistair, the camp director. He was kind of red in the face, and he had a lot of white hair that stuck out all around his shining bald head. He was supposedly this very famous conductor, but let me ask you: If he's so famous, what's he doing running what boils down to a glorified band camp in northern Indiana?

"Pamela," he said, looking irritated. "There's a young man on the phone looking for one of the counselors. I told him that we are not running an answering service here, and that if he wants to speak to one of our employees, he can leave a message like everybody else and we will post it on the message board. But he says it's an emergency, and—"

I moved so fast, I almost knocked over a chair.

"Is it for me? Jess Mastriani?"

It wasn't any psychic ability that told me that phone call was probably for me. It was the combination of the words "young man" and "emergency." All of the young men of my acquaintance, when confronted by someone like Dr. Alistair, would definitely go for the word "emergency" as soon as they heard about that stupid message board.

Dr. Alistair looked surprised … and not too pleased.

"Why, yes," he said. "If your name is Jessica, then it is for you. I hope Pamela has explained to you the fact that we are not running a message service here, and that the making or receiving of personal calls, except during Sunday afternoons, is expressly—"

"But it's an emergency," I reminded him.

He grimaced. "Down the hall. Phone at the reception desk. Press line one."

I was out of Pamela's office like a shot.

Who, I wondered, as I jogged down the hall, could it be? I knew who I wanted it to be. But the chances of Rob Wilkins calling me were slim to none. I mean, he never calls me at home. Why would he call me at camp?

Still, I couldn't help hoping Rob had overcome this totally ridiculous prejudice he's got against me because of my age. I mean, so what if he's eighteen and has graduated already, while I still have two years of high school left? It's not like he's leaving town to go to college in the fall, or something. Rob's not going to college. He has to work in his uncle's garage and support his mother, who recently got laid off from the factory she had worked in for like twenty years or something. Mrs. Wilkins was having trouble finding another job, until I suggested food services and gave her the number at Joe's. My dad, without even knowing Mrs. Wilkins and I were acquainted, hired her and put her on days at Mastriani's—which isn't a bad shift at all. He saves the totally crappy jobs and shifts for his kids. He believes strongly in teaching us what he calls a "work ethic."

But when I got to the phone and pushed line one, it wasn't Rob. Of course it wasn't Rob. It was my brother Douglas.

And that's how I really knew it wasn't an emergency. If it had been an emergency, it would have been about Douglas. The only emergencies in our family are because of Douglas. At least, they have been, ever since he got kicked out of college on account of these voices in his head that are always telling him to do stuff, like slit his wrists, or stick his hand in the barbecue coals. Stuff like that.

But so long as he takes his medicine, he's all right. Well, all right for Douglas, which is kind of relative.

"Jess," he said, after I went, "Hello?"

"Oh, hey." I hoped my disappointment that it was Douglas and not Rob didn't show in my voice.

"How's it going? Who was that freak who answered the phone? Is that your boss, or something?"

Douglas sounded good. Which meant he'd been taking his medication. Sometimes he thinks he's cured, so he stops. That's when the voices usually come back again.

"Yeah," I said. "That was Dr. Alistair. We aren't supposed to get personal calls, except on Sunday afternoons. Then it's okay."

"So he explained to me." Douglas didn't sound in the least bit ruffled by his conversation with Dr. Alistair, world-famous orchestra conductor. "And you prefer working for him over Dad? At least Dad would let you get phone calls at work."

"Yeah, but Dad would withhold my pay for the time I spent on the phone."

Douglas laughed. It was good to hear him laugh. He doesn't do it very often anymore.

"He would, too," he said. "It's good to hear your voice, Jess."

"I've only been gone a week," I reminded him.

"Well, a week's a long time. It's seven days. Which is one hundred and sixty-eight hours. Which is ten thousand, eighty minutes. Which is six hundred thousand, four hundred seconds."

It wasn't the medication that was making Douglas talk like this. It wasn't even his illness. Douglas has always gone around saying stuff like this. That's why, in school, he'd been known as The Spaz, and Dorkus, and other, even worse names. If I'd asked him to, Douglas could tell me exactly how many seconds it would be before I got back home. He could do it without even thinking about it.

But go to college? Drive a car? Talk to a girl to whom he wasn't related? No way. Not Douglas.

"Is that why you called me, Doug?" I asked. "To tell me how long I've been gone?"

"No." Douglas sounded offended. Weird as he is, he doesn't think he's the least unusual. Seriously. To Douglas, he's just, you know, average.

Yeah. Like your average twenty-year-old guy just sits around in his bedroom reading comic books all day long. Sure.

And my parents let him! Well, my mom, anyway. My dad's all for making Doug work the steam table in my absence, but Mom keeps going, "But Joe, he's still recovering. . . ."

"I called," Douglas said, "to tell you it's gone."

I blinked. "What's gone, Douglas?"

"You know," he said. "That van. The white one. That's been parked in front of the house. It's gone."

"Oh," I said, blinking some more. "Oh."

"Yeah," Douglas said. "It left the day after you did. And you know what that means."

"I do?"

"Yeah." And then, I guess because it was clear to him that I wasn't getting it, he elaborated. "It proves that you weren't being paranoid. They really are still spying on you."

"Oh," I said. "Wow."

"Yeah," Douglas said. "And that's not all. Remember how you told me to let you know if anyone we didn't know came around, asking about you?"

I perked up. I was sitting at the receptionist's desk in the camp's administrative offices. The receptionist had gone home for the day, but she'd left behind all her family photos, which were pinned up all around her little cubicle. She must have really liked NASCAR racing, because there were a lot of photos of guys in these junky-looking race cars.

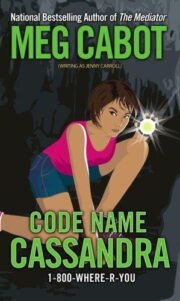

"Code Name Cassandra" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Code Name Cassandra". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Code Name Cassandra" друзьям в соцсетях.