"Ow!" Shane cried, shooting me an indignant look. "What'd you do that for?"

"While you are living in Birch Tree Cottage," I informed him—as well as the rest of the boys, who were staring at us—"you will conduct yourself as a gentleman, which means you will refrain from making overtly sexual references within my hearing. Additionally, you will not insult other people's countries of origin."

Shane's face was a picture of confusion. "Huh?" he said.

"No sex talk," John translated for him.

"Aw." Shane looked disgusted. "Then how am I supposed to have any fun?"

"You will have good, clean fun," I informed him. "And that's where the official Birch Tree Cottage song comes in."

And then, while we undertook the long walk to the dining hall, I taught them the song.

I met a miss,

She had to pi—

—ck a flower.

Stepped in the grass,

up to her a—

—nkle tops.

She saw a bird,

stepped on a tur—

—key feather.

She broke her heart,

and let a far—

—mer carry her home.

"See?" I said as we walked. We had the longest walk of anyone to the dining hall, so by the time we'd reached it, the boys had the song entirely memorized. "No dirty words."

"Almost dirty," Doo Sun said with relish.

"That's the stupidest song I ever heard," Shane muttered. But I noticed he was singing it louder than anyone as we entered the dining hall. None of the other cabins, we soon learned, had official songs. The residents of Birch Tree Cottage sang theirs with undisguised gusto as they picked up their trays and got into the concession line.

I spied Ruth sitting with the girls from her cabin. She waved to me. I sauntered over.

"What is going on?" Ruth wanted to know. "What are you doing with all those boys?"

I explained the situation. When she had heard all, Ruth's mouth fell open and she went, her blue eyes flashing behind her glasses, "That is so unfair!"

"It'll be all right," I said.

"What will?" Shelley, a violinist and one of the other counselors, came by with a tray loaded down with chili fries and Jell-O.

Ruth told her what had happened. Shelley looked outraged.

"That is bull," she said. "A boys' cabin? How are you going to take a shower?"

Seeing everyone else so mad on my behalf, I started feeling less bad about the whole thing. I shrugged and said, "It won't be so bad. I'll manage."

"I know what you can do," Shelley said. "Just shower at the pool, in the girls' locker room."

"Or one of the guys from the cabins near yours can keep your campers occupied," Ruth said. "I mean, it wouldn't kill Scott or Dave to take on some extra kids for half an hour, here and there."

"What won't kill us?" Scott, an oboe player with thick glasses who'd nevertheless been judged Do-able thanks to his height (a little over six feet) and thighs (muscular) came over, followed closely by his shadow, a stocky Asian trumpet player named Dave … also rated Do-able, courtesy of a set of surprisingly washboard abs.

"They reassigned Jess to a boys' cabin," Shelley informed them.

"No kidding?" Scott looked interested. "Which one?"

"Birch," I said carefully.

Scott and Dave exchanged enthusiastic glances.

"Hey," Scott cried. "That's right near us! We're neighbors!"

"That was you?" Dave grinned down at me. "Who waved at me?"

"Yeah," I said. But you waved first.

I didn't say that part out loud, though. I wondered if either Dave or Scott had a convertible. I doubted it.

Not that I cared. I was taken, anyway. Well, in my opinion, at least.

"Don't worry, Jessica," Dave said, with a wink. "We'll look after you."

Just what I needed. To be looked after by Scott and Dave. Whoopee.

Ruth speared a piece of lettuce. She was eating a salad, as usual. Ruth would starve herself all summer in order to look good in a bikini she would never quite work up the courage to wear. If Scott or Dave or, well, anybody, for that matter, did ask her to go with him to the dunes, she would go dressed in a T-shirt and shorts that she would not remove, even in the event of heat stroke.

Ruth eyed me over a forkful of romaine. "What was with that dirty song you had those guys singing when you all came in?"

"It wasn't dirty," I said.

"It sounded dirty." Scott, who'd taken a seat on Ruth's other side, instead of sitting with his cabin, like he was supposed to, was eating spaghetti and meatballs. He was doing it wrong, too, cutting the pasta up into little bite-sized portions, instead of twirling it on his fork. My dad would have had an embolism.

Scott, I decided, must like Ruth. I knew Ruth liked Todd, the hot-looking violinist, but Scott wasn't such a bad guy. I hoped she'd give him a chance. Oboe players are generally better humored than violinists.

"Technically," I said, "that song wasn't a bit dirty."

"Oh, God," Ruth said, making a face at something she'd spotted over my shoulder. "What's she doing here?"

I looked around. Standing behind me was Karen Sue Hanky. I hadn't seen Karen Sue since school had let out for the summer, but she looked much the same as she always did—rat-faced and full of herself. She was holding a tray laden with grains and legumes. Karen Sue is vegan.

Then I noticed that beside Karen Sue stood Pamela.

"Excuse me, Jess?" Pamela said. "Can I see you for a moment in my office, please?"

I shot Karen Sue a dirty look. She simpered back at me.

This was going to be, I realized, a long summer.

In more ways than one.

C H A P T E R

3

"It wasn't dirty," I said as I followed Pamela into her office.

"I know," Pamela said. She collapsed into the chair behind her desk. "But it sounds dirty. We've had complaints."

"Already?" I was shocked. "From who?"

But I knew. Karen Sue, on top of the whole vegan thing, is this total prude.

"Look," I said, "if it's that much of a problem, I'll tell them they can't sing it anymore."

"Fine. But to tell you the truth, Jess," Pamela said, "that's not really why I called you in here."

All of a sudden, it felt as if someone had poured the contents of a Big Gulp down my back.

She knew. Pamela knew.

And I hadn't even seen it coming.

"Look," I said. "I can explain."

"Oh, can you?" Pamela shook her head. "I suppose it's partly our fault. I mean, how the fact that you're the Jessica Mastriani slipped through our whole screening process, I cannot imagine. . . ."

Visions of steam tables danced in my head.

"Listen, Pamela." I said it low, and I said it fast. "That whole thing—the getting struck by lightning thing? Yeah, well, it's true. I mean I was struck by lightning and all. And for a while, I did have these special powers. Well, one, anyway. I mean, I could find lost kids and all. But that was it. And the thing is—well, as you probably know—it went away."

I said this last part very loudly, just in case my old friends, Special Agents Johnson and Smith, had the place bugged or whatever. I hadn't noticed any white vans parked around the campgrounds, but you never knew. . . .

"It went away?" Pamela was looking at me nervously. "Really?"

"Uh-huh," I said. "The doctors told me it probably would. You know, after the lightning was done rattling around in me and all." At least, that was how I liked to think about it. "And it turned out they were right. I am now totally without psychic power. So, um, there's really nothing for you to worry about, so far as negative publicity for the camp, or hordes of reporters descending on you, or anything like that. The whole thing is totally over."

Not even remotely true, of course, but what Pamela didn't know couldn't, I figured, hurt her.

"Don't get me wrong, Jess," she said. "We love having you here—especially with you being so good about changing cabins—but Camp Wawasee has never known a single hint of controversy in the fifty years it's been in existence. I'd hate for … well, anything untoward to happen while you're here. . . ."

Untoward was, I guess, Pamela's way of referring to what had happened last spring, after I'd been struck by lightning and then got "invited" to stay at Crane Military for a few days, while some scientists studied my brain waves and tried to figure out how it was that, just by showing me a picture of a missing person, I could wake up the next morning knowing exactly where that person was.

Unfortunately, after they'd studied it for a while, the people at Crane had decided that my newfound talent might come in handy for tracking down so-called traitors and other unsavory individuals who really, as far as I knew, didn't want to be found. And while I'm as anxious as anybody to incarcerate serial killers and all, I just figured I'd stick to finding missing kids … specifically, kids who actually want to be found.

Only the people at Crane had turned out to be surprisingly unhappy to hear this.

But after some friends of mine and I had broken some windows and cut through some fencing and, oh, yeah, blown up a helicopter, they came around. Well, sort of. It helped, I guess, that I called the press and told them I couldn't do it anymore. Find missing people, I mean. That little special talent of mine just dried up and blew away. Poof.

That's what I told them, anyway.

But you could totally see where Pamela was coming from. On account of the fireball caused by the exploding helicopter and all. It had made a lot of papers. You don't get fireballs every day. At least, not in Indiana.

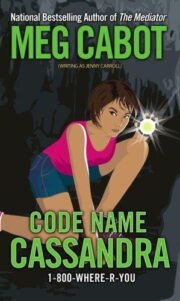

"Code Name Cassandra" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Code Name Cassandra". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Code Name Cassandra" друзьям в соцсетях.