He was frowning a little, and asked abruptly: “Does he subject you to that sort of Turkish treatment, Mama?”

“Oh, no, never! To be sure, he does sometimes scold me, but he has never thrown anything at me—not even when I ventured to suggest that he should add some rhubarb and water to his port, which is an excellent remedy for a deranged stomach, you know, but he would have none of it. In fact, it put him into a regular flame.”

“I’m not surprised!” said the Viscount, laughing at her. “You almost deserved to have it thrown at you, I think!”

“Yes, that’s what he said, but he didn’t throw it at me. He burst out laughing, just as you did. What made him suddenly so vexed, dearest? Did you say something to make him pucker up? I know you haven’t done anything to displease him, for he was delighted to see you. Indeed, that is why we had the dressed crab, and he made Pedmore bring up the best port.”

“Good God, in my honour, was it? Of course, I dared not tell him so, but I’m not at all fond of port, and I had to drink the deuce of a lot of it. As for what vexed him, it was certainly nothing I said, for not an unwise word passed my lips! I can only suppose that the crab and the port were responsible.” He paused, thinking of what had passed in the library, the frown returning to his brow. He turned his eyes towards his mother, and said slowly: “And yet—Mama, what made him hark back, after all this time, to the match he tried to make between Hetta and me, when I was twenty?”

“Oh, did he do so? How unfortunate!”

“But why did he, Mama? He hasn’t spoken of it for years!”

“No, and that is what one particularly likes about him. He has a shockingly quick temper, but he never sinks into the mopes, or rubs up old sores. The thing is, I fear, that it has all been brought back to his mind because he has been told that at last dear Henrietta seems likely to contract a very eligible alliance.”

“Good God!” exclaimed the Viscount. “You don’t mean it! Who’s the suitor?”

“I shouldn’t think you know him, for he has only lately come into Hertfordshire, and I fancy he very rarely goes to London. He is old Mr Bourne’s cousin, and inherited Marley House from him. According to Lady Draycott, he is an excellent person, of the first respectability, a thousand agreeable talents, and most distinguished manners. I haven’t met him myself, but I do hope something may come of it, for I have the greatest regard for Henrietta, and have always wished to see her comfortably established. And, if Lady Draycott is to be believed, this Mr—Mr Nethersole—no, not Nethersole, but some name like that—seems to be just the man for her.”

“He sounds to me like a dashed dull dog!” said the Viscount.

“Yes, but persons of uniform virtues always do sound dull, Ashley. It seems to me such an odd circumstance! However, we must remember that Lady Draycott is not wholly to be relied on, and I daresay she has exaggerated. She thinks everyone she likes a pattern-saint, and everyone she doesn’t like a rascal.” Her eyes twinkled. “Well, she says you are a man of character, and very well conducted!”

“Much obliged to her!” said the Viscount. “To think she should judge me so well!”

She laughed. “Yes, indeed! It is a striking example of the advantage of having engaging manners. What a sad reflection it is that to have powers of captivation should be of much more practical use than worthiness!” She leaned forward to pinch his chin, her eyes full of loving mockery. “You can’t bamboozle me, you rogue! You are a here-and-thereian, you know, exactly as I am persuaded Papa told you! I wish you might form a tendre for some very nice girl, and settle down with her! Never mind! I don’t mean to tease you!”

She withdrew her hand, but he caught it, and held it, saying, with a searching look: “Do you, Mama? Did you, perhaps, wish me to offer for Hetta, nine years ago? Would you have liked her to have been your daughter-in-law?”

“What a very odd notion you have of me, my love! I hope I am not such a pea-goose as to have wished you to marry any girl for whom you had formed no lasting passion! To be sure, I have a great regard for Hetta, but I daresay you would not have suited. In any event, that has been past history for years, and nothing is such a bad bore as to be recalling it! I promise you, I shall welcome the bride you do choose at last with as much pleasure as I shall attend Hetta’s wedding to the man of her choice.”

“What, to the pattern-card whose name you can’t remember? Are the Silverdales at Inglehurst? I haven’t seen Hetta in town for weeks, but from what she told me when we met at the Castlereaghs’ ball I had supposed that she must by now have been fixed at Worthing, poor girl!”

“Lady Silverdale,” said his mother, in an expressionless voice, “finding that the only lodging she could tolerate in Worthing was not available this summer, has recollected that the sea-air always makes her bilious, and has chosen to retire to Inglehurst rather than to seek a lodging at some other resort.”

“What an abominable woman she is!” said the Viscount cheerfully. “Oh, well! I daresay Hetta will be better off with her pattern-card! I’ll drop in at Inglehurst tomorrow, on my way back to London, and try to discover what this fellow, Nether-what’s-it, is really like!”

Slightly taken aback, Lady Wroxton said, in mild expostulation: “My dear boy, you cannot, surely, question Hetta about him?”

“Lord, yes! of course I can!” said the Viscount. “There are no secrets between Hetta and me, Mama, any more than there are between Griselda and me—in fact,” he added, subjecting this confident assertion to consideration, “far fewer!”

Chapter 2

Viscount Desford left his ancestral home on the following morning without seeking another interview with his father. Since the Earl rarely left his bed-chamber before noon, this was not difficult. The Viscount partook of an excellent breakfast in solitary state; ran upstairs to bid his mother a fond farewell, issued a few final directions to his valet, who was to follow him into Hampshire with his baggage, and mounted into his curricle as the stable clock began to strike eleven. By the time the echoes of its last stroke had died he was out of sight of the house, bowling down the long avenue that led to the main gates.

The pace at which he drove his mettlesome horses might have alarmed persons of less iron nerve than the middle-aged groom who sat beside him; but Stebbing, who had served him ever since his boyhood, had a disposition which matched his square, severe countenance, and sat with his arms folded across his chest, and an expression on his face of complete unconcern, As little as he betrayed alarm did he betray his pride in the out-and-outer whom he had taught to ride his first pony, and who had become, as well as an accomplished fencer, a first-rate dragsman. Only in the company of his intimates did he say, over a heavy wet, that, taking him in harness and out, no man could do more with his horses than my Lord Desford could.

The curricle which Desford was driving was not precisely a racing curricle, but it had been built to his own design by Hatchett, of Longacre, so lightly that it was very easy on his horses, and capable (if drawn by the sort of blood cattle his lordship kept in his stables) of covering long distances in an incredibly short space of time. In general, Desford drove with a pair only under the pole, but if he set out on a long journey he had a team harnessed to the carriage, demonstrating (so said his ribald cronies) that he was bang up to the knocker. He was driving a team of splendid grays on this occasion, and if they were not the sixteen-mile an hour tits so frequently advertised for sale in the columns of the Morning Post they reached the Viscount’s immediate destination considerably before noon, and without having once been allowed to break out of a fast trot.

Inglehurst Place was a very respectable estate owned, until his death some years previously, by a lifelong friend of Lord Wroxton’s. Its present owner, Sir Charles Silverdale, had inherited it from his father when still at Harrow, and he had not yet come into his majority, or (according to those who shook sad heads over his rackety ways) shown the least desire to assume the responsibilities attached to his inheritance. His fortune was controlled by his trustees, but since neither of these two gentlemen whose lives had been devoted to the Law had any but a superficial understanding of country matters the management of the estate was shared by Sir Charles’s bailiff, and his sister, Miss Henrietta Silverdale.

The butler, a very stately personage, accorded the Viscount a bow, and said that he regretted to be obliged to inform him that her ladyship, having passed an indifferent night, had not yet come downstairs, and so could not receive him.

“Come down from your high ropes, Grimshaw!” said the Viscount. “You know dashed well I haven’t come to visit her ladyship! Is Miss Silverdale at home?”

Grimshaw unbent sufficiently to say that he thought Miss would be found in the garden, but his expression, as he watched Desford stride off round the corner of the house, was one of gloomy disapproval.

The Viscount found Miss Silverdale in the rose-garden, attended by two gentlemen, one of whom was known to him, and the other a stranger. She greeted him with unaffected pleasure, exclaiming: “Des!” and stretching out her hands to him. “I had supposed you to be in Brighton! What brings you into Hertfordshire?”

The Viscount took her hands, but kissed her cheek, and said: “Filial piety, Hetta! How do you do my dear? Not that I need ask! I can see you’re in high force!” He nodded and smiled at the younger of the two gentlemen present, and looked enquiringly at the other.

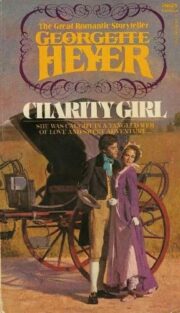

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.