Perhaps he’d made a strategic mistake by avoiding the London Season and the possibilities of running into her. By staying away, he also deprived himself of a large pool of young women. Who was to say he would not find among them someone who could take his mind permanently off her?

A knock came. Christian opened the door himself—he’d given his valet two weeks’ leave to visit his brother, who’d immigrated to New York. A very young porter bowed and handed him a note from Mrs. Winthrop, a fellow guest at the hotel who had been throwing herself at him for the past three days.

Christian badly needed a distraction, but he liked to uphold a minimum of standards in his dalliances. Mrs. Winthrop, unfortunately, was not only excessively vain, but more than a little stupid. Judging by her newest invitation, she also could not take a hint.

“Send Mrs. Winthrop some flowers with my regrets,” he said to the porter.

“Yes, sir.”

His gaze landed on the Central Park map on the console table. “And return the map to the Baroness von Seidlitz-Hardenberg.”

The porter bowed again and left.

Christian walked out onto the balcony of his suite and looked down. The height was perilous, the air abrupt and chill. The pedestrians were the size of drawing dolls, jointed mannequins milling about the pavement.

A woman emerged from the hotel: Baroness von Seidlitz-Hardenberg, as evidenced by her daft hat. The rest of her, however, was altogether shapely—a figure meant for reproduction. Product of evolution that he was, even though he had no intention of procreating with her, he was still coaxed out of his preoccupation to contemplate the obvious pleasures of her form.

In the confines of the lift, her attention had all but licked him from head to toe.

He was not unpopular either at home or abroad. Still, the baroness’s interest had been extraordinarily intense, all the more so for the fact that she never once directly gazed at him.

Now, however, she did. From sixteen stories below, she looked up over her shoulder and unerringly located him, a glance that he felt through the cream netting that concealed her face. Then she crossed the street and disappeared under the trees of Central Park.

Venetia was vaguely aware of the trees, the ponds and bridges, the young men and women zipping by on their safety bicycles. The sea lions at the menagerie barked; the children clamored to see the polar bears; a violin wailed the mournful notes of “Méditation” from Thaïs—yet all she heard was the duke’s inescapable voice.

The lady would like your best rooms.

The lady wishes to go to the fifteenth floor.

Your map, madam.

He had no right to appear helpful and gentlemanly, he who’d judged her as if he knew everything there was to know about her. When he knew nothing—nothing at all.

Yet she was the one who felt ashamed that her husband had despised her so much. She could have continued in her blissful ignorance had the duke had the decency to keep a private conversation private. But he hadn’t, and his revelation would haunt her always.

She wanted—needed—to do something to knock him off his arrogant, comfortable perch. Actions carried consequences. He would not decimate her good name and not pay a price for it.

But what could she do? She could not sue him on grounds of defamation, as he’d never named her. She knew no dirty secrets of his that she could spill in return. And even if she warned every woman under the age of sixty-five of his savageness of spirit, his title and wealth would still ensure he’d have the wife of his choice.

It was dark by the time she returned to the hotel, her feet sore, her head throbbing. The lift was empty save for the lift attendant, but as it ascended, the duke might as well have been there, taunting her with his invulnerability.

She smelled the lilies as soon as she opened the doors to her suite. A large peach bloom vase that hadn’t been there before occupied the center table of the sitting room. From the vase, aggressively tall stalks of white calla lilies and orange gladiolus shot toward the ceiling, their petals glaring in the electric light.

Her family would never send her calla lilies, a cascade of which she’d carried when she walked down the aisle to marry Tony. She plucked the card from the fronds that buttressed the flowers.

The Duke of Lexington regrets his departure from New York and hopes for the pleasure of your company another day, madam.

The gall of the man. The extravagant bouquet was nothing but an announcement that should they meet again, he’d like for her to be waiting in bed, already naked. So he despised Venetia Easterbrook’s soul, but liked her backside well enough when he didn’t know to whom it belonged.

She tore the card in two. In four. In eight. And kept tearing, choking on her impotence.

Helena’s words leaped to mind. Avenge yourself, Venetia. Make him fall in love with you, then give him the cut.

Why not?

What would it be to him? Merely a dalliance gone wrong. He’d hurt for a few short weeks—a few months, if she was lucky. But she, she would go through the rest of her life oppressed by the weight of his disclosure.

She telephoned the concierge and asked for a first-class stateroom on the Rhodesia, as close to the Victoria suites as possible. And then she sat down to write Helena and Millie a note concerning her sudden exit.

It was only as she sealed the note that she thought of the specifics of her seduction. How would she manage to breach his defenses when he had such entrenched preconceptions about her? When he’d take one look at her face, otherwise her greatest asset in a quest of such nature, and turn away?

No matter. She’d have to be creative, that was all. Where there’s a will, there’s a way. And with every fiber of her being, she willed that the Duke of Lexington would regret the day he chose to stick a knife into her kidney.

CHAPTER 4

Lexington stood at the rail and surveyed the hive of activity beneath him.

Carriages and heavy drays drove on and off the dock, their procession surprisingly speedy and orderly. Trunks and crates, hefted by stevedores with meaty shoulders and bulging upper arms, slid down open chutes into the cargo hold. Tugboats tooted at one another, readying themselves to nudge the great ocean liner’s nose around—for her to head toward the open sea.

Up the gangplank came the ship’s passengers: giggling young women who had never before crossed the pond; indifferent men of business on their third trip of the year; children pointing excitedly at the ship’s smokestacks; immigrant workers—largely Irish—returning to the old country for a brief visit.

The man in a hat too fancy for his clothes was likely to be a swindler, planning to “aggregate funds” from his fellow passengers for an “extraordinary, once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.” The lady’s companion, plainly dressed and seemingly demure, examined first-class gentlemen passengers with mercenary interest: She did not intend to remain a lady’s companion forever—or even for much longer. The adolescent boy who stared contemptuously at the back of his puffy, sweaty father appeared ready to disown the unimpressive sire and invent an entirely new patrimony for himself.

But what hypothesis should he form concerning Baroness von Seidlitz-Hardenberg, for that was her coming up the gangplank, was it not? He recognized her hat, almost like that of a beekeeper’s, but sleeker and more shimmery. The day before, the veil had been creamy in color. Today it was blue, to complement her blue traveling gown.

Logically, a woman shouldn’t need to don a traveling gown for the two and a half miles between Hotel Netherlands and the Forty-second Street piers on the Hudson River, where the Rhodesia was docked. But he’d long ago given up trying to apply logic to fashion, the offspring of irrationality and inconstancy.

The degree of a woman’s devotion to fashion frequently corresponded to her degree of silliness. He’d learned to pay no attention to any woman with a stuffed macaw in her hat and to expect shoddy food at the home of a hostess best known for her collection of ball gowns.

The baroness was certainly highly fashionable. And restless: The unusual parasol in her hand, white with a pattern of concentric blue octagons, twirled constantly. But she did not come across as silly.

She looked up. He could not quite tell whether she was looking directly at him. But whatever she saw, she halted midstep. Her parasol stopped spinning; the tassels around the fringe swayed back and forth with the sudden loss of momentum.

But only for a second. She resumed her progress on the gangplank, her parasol again a hypnotic pinwheel.

He watched her until she disappeared into the first-class entrance.

Was she the distraction he badly needed?

A hush always descended in the final moments before departure, quiet enough to hear the commands issued from the bridge and passed along the length of the ship. The harbor slipped away. On the main deck below her, the crowd waved madly at the loved ones they were leaving behind. The throngs on the dock waved back, just as earnest and demonstrative.

Venetia’s throat tightened. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d felt such unbridled, unabashed emotions.

Or when she last dared to.

“Good morning, baroness.”

She jerked. Lexington stood a few feet away, an ungloved hand on the railing, dressed casually in a gray lounge suit and a felt hat that had probably seen service on his expeditions. He regarded the waterfront of New York, its piers, cranes, and warehouses sliding past, and displayed no interest in her whatsoever.

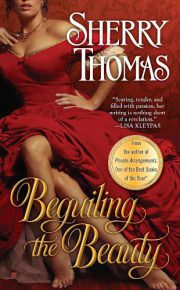

"Beguiling the Beauty" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beguiling the Beauty". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beguiling the Beauty" друзьям в соцсетях.