Distantly she realized that she knew nothing of the earl’s character, sense, or temperament. That she was behaving in a shallow and foolish manner, putting the cart before the horse. But the chaos inside her had a life and a will of its own.

As they entered the drawing room, Mrs. Clements said, “What a lovely table. Don’t you agree, Fitz?”

“I do,” said the earl.

His name was George Edward Arthur Granville Fitzhugh—the family name and the title were the same. But apparently those who knew him well called him Fitz.

Fitz, her lips and teeth played with the syllable. Fitz.

At dinner, the earl let Colonel Clements and Mrs. Graves carry the majority of the conversation. Was he shy? Did he still obey the tenet that children should be seen and not heard? Or was he using the opportunity to assess his possible future in-laws—and his possible future wife?

Except he didn’t appear to be studying her. Not that he could do so easily: a three-tier, seven-branch silver epergne, sprouting orchids, lilies, and tulips from every appendage, blocked the direct line of sight between them.

Through petals and stalks, she could make out his occasional smiles—each of which made her ears hot—directed at Mrs. Graves to his left. But he looked more often in her father’s direction.

Her grandfather and her uncle had built the Graves fortune. Her father had been young enough, when the family coffer began to fill, to be sent to Harrow. He’d acquired the expected accent, but his natural temperament was too lackluster to quite emanate the gloss of sophistication his family had hoped for.

There he sat at the head of the table, neither a ruthless risk taker like his late father, nor a charismatic, calculating entrepreneur like his late brother, but a bureaucrat, a caretaker of the riches and assets thrust upon him. Hardly the most exciting of men.

Yet he commanded the earl’s attention this night.

Behind him on the wall hung a large mirror in an ornate frame, which faithfully reflected the company at table. Millie sometimes looked into the mirror and pretended that she was an outside observer documenting the intimate particulars of a private meal. But tonight she had yet to give the mirror a glance, since the earl sat at the opposite end of the table, next to her mother.

She found him in the mirror. Their eyes met.

He had not been looking at her father. Via the mirror, he’d been looking at her.

Mrs. Graves had been forthcoming on the mysteries of marriage—she did not want Millie ambushed by the facts of life. The not-so-pretty reality of what happened between a man and a woman behind closed doors usually had Millie regard members of the opposite sex with wariness. But his attention caused only fireworks inside her—a detonation of thrill, a blast of full-fledged happiness.

If they were married, and if they were alone …

She flushed.

But she already knew: She would not mind it.

Not with him.

The gentlemen had barely rejoined the ladies in the drawing room when Mrs. Graves announced that Millie would play for the gathering.

“Millicent is splendidly accomplished at the pianoforte,” she said.

For once, Millie was excited about the prospect of displaying her skills—she might lack true musicality, but she did possess an ironclad technique.

Mrs. Graves turned to Lord Fitzhugh. “Do you enjoy music, sir?”

“I do, most assuredly,” he answered. “May I be of some use to Miss Graves? Turn the pages for her perhaps?”

Millie braced her hand on the music rack. The bench was not very long. He’d be sitting right next to her.

“Please do,” said Mrs. Graves.

And just like that, Lord Fitzhugh was at Millie’s side, so close that his trousers brushed the flounces of her skirts. He smelled fresh and brisk, like an afternoon in the country. And the smile on his face as he murmured his gratitude distracted her so much that she forgot that she should be the one to thank him.

He looked away from her to the score on the music rack. “Moonlight Sonata. Do you have something lengthier?”

The question rattled—and pleased—her. “Usually one only hears the first movement of the sonata, the adagio sostenudo. But there are two additional movements. I can keep playing, if you’d like.”

“I’d be much obliged.”

A good thing she played mechanically and largely from memory, for she could not concentrate on the notes at all. The tips of his fingers rested lightly against a corner of the score sheet. He had lovely looking hands, strong and elegant. She imagined one of his hands gripped around a cricket ball—it had been mentioned at dinner that he played for the school team. The ball he bowled would be fast as lightning. It would knock over a wicket directly and dismiss the batter to the roar of the crowd’s appreciation.

“I have a request, Miss Graves,” he spoke very quietly.

With her playing, no one could hear him but her.

“Yes, my lord?”

“I’d like you to keep playing no matter what I say.”

Her heart skipped a beat. Now it was beginning to make sense. He wanted to sit next to her so that they could hold a private conversation in a room full of their elders.

“All right. I’ll keep playing,” she said. “What is it that you want to say, sir?”

“I’d like to know, Miss Graves, are you being forced into marriage?”

Ten thousand hours before the pianoforte was the only thing that kept Millie from coming to an abrupt halt. Her fingers continued to pressure the correct keys; notes of various descriptions kept on sprouting. But it could have been someone in the next house playing, so dimly did the music register.

“Do I—do I give the impression of being forced, sir?” Even her voice didn’t quite sound her own.

He hesitated slightly. “No, you do not.”

“Why do you ask then?”

“You are sixteen.”

“It isn’t unheard of for a girl to marry at sixteen.”

“To a man more than twice her age?”

“You make the late earl sound decrepit. He was a man in his prime.”

“I am sure there are thirty-three-year-old men who make sixteen-year-olds tremble in romantic yearning, but my cousin was not one of them.”

They were coming to the end of the page; he turned it just in time. She chanced a quick glance at him. He did not look at her.

“May I ask you a question, my lord?” she heard herself say.

“Please.”

“Are you being forced to marry me?”

The words left her in a spurt, like arterial bleeding. She was afraid of his answer. Only a man who was himself being forced would wonder whether she too was under the same duress.

He was silent for some time. “Do you not find this kind of arrangement exceptionally distasteful?”

Glee and misery—she’d been bouncing between the two wildly divergent emotions. But now there was only misery left, a sodden mass of it. His tone was perfectly courteous. Yet his question was an accusation of complicity: He would not be here if she hadn’t agreed.

“I—” She was playing the adagio sostenudo much too fast—no moonlight in her sonata, only storm-driven branches whacking at shutters. “I suppose I’ve had time to become inured to it: I’ve known my whole life that I’d have no say in the matter.”

“My cousin held out for years,” said the earl. “He should have done it sooner: beget an heir and leave everything to his own son. We are barely related.”

He did not want to marry her, she thought dazedly, not in the very least.

This was nothing new. His predecessor had not wanted to marry her, either; she had accepted his reluctance as par for the course. Had never expected anything else, in fact. But the unwillingness of the young man next to her on the piano bench—it was as if she’d been forced to hold a block of ice in her bare hands, the chill turning into a black, burning pain.

And the mortification of it, to be so eager for someone who reciprocated none of her sentiments, who was revolted by the mere thought of taking her as a wife.

He turned the next page. “Do you never think to yourself, I won’t do it?”

“Of course I’ve thought of it,” she said, suddenly bitter after all these years of placid obedience. But she kept her voice smooth and uninflected. “And then I think a little further. Do I run away? My skills as a lady are not exactly valuable beyond the walls of this house. Do I advertise my services as a governess? I know nothing of children—nothing at all. Do I simply refuse and see whether my father loves me enough to not disown me? I’m not sure I have the courage to find out.”

He rubbed the corner of a page between his fingers. “How do you stand it?”

This time there was no undertone of accusation to his question. If she wanted to, she might even detect a bleak sympathy. Which only fed her misery, that foul beast with teeth like knives.

“I keep myself busy and do not think too deeply about it,” she said, in as harsh a tone as she’d ever allowed herself.

There, she was a mindless automaton who did as others instructed: getting up, going to sleep, and earning heaps of disdain from prospective husbands in between.

They said nothing more to each other, except to exchange the usual civilities at the end of her performance. Everyone applauded. Mrs. Clements said very nice things about Millie’s musicianship—which Millie barely heard.

The rest of the evening lasted the length of Elizabeth’s reign.

Mr. Graves, usually so phlegmatic and taciturn, engaged the earl in a lively discussion of cricket. Millie and Mrs. Graves gave their attention to Colonel Clements’s army stories. Had someone looked in from the window, the company in the drawing room would appear perfectly normal, jovial even.

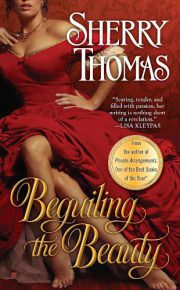

"Beguiling the Beauty" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beguiling the Beauty". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beguiling the Beauty" друзьям в соцсетях.