“I’ve spent some time in Berlin and you don’t have the vowels of Prussia proper, either the German parts or the Polish parts. You sound as if your origins are farther south—Bavaria, I’d say.”

Her German governess had indeed been from Munich and spoke the lilting Bairisch dialect. “Very good for an Englishman.”

“Yet I’m not convinced you are German.”

Too good for an Englishman. “Why not? You yourself identified my Bavarian accent.”

“When I mentioned your accent, you stopped cold. You are still standing in place, by the way.”

She remained where she was. “Does it matter whether I am German, Hungarian, or Polish?”

“No, I suppose it doesn’t. Is your name really von Seidlitz-Hardenberg?”

“And what if I am not a baroness, either? Will that cause the Rhodesia to sink?”

“No, but I’m convinced it precipitated the storm.”

Judging by his tone, he was smiling once more—and standing all too close.

His hand combed her hair. “What are you still afraid of?”

“I’m not afraid of anything.” Yet she sounded as if she were cowering.

“Good, you shouldn’t be. What can I do to you? Once we disembark, I wouldn’t know you even if we came face-to-face.”

But she’d planned differently, hadn’t she? At Southampton, she meant to reveal herself and let him know he’d been had. She’d imagined this denouement in dozens of delicious variations, each leading to that inevitable point of rage and devastation on his part. Looking back, it was as if she’d planned a trip to the moon, with her only qualification an enthusiasm for Monsieur Verne’s scientific romances.

He tucked back her hair and kissed her beneath her earlobe, the sensation so jagged it almost hurt. Nibbling a path down the column of her neck, he pushed aside the collar of her dressing gown and exposed her shoulder.

“You are so very tense again, my dear baroness who may or may not be a baroness.”

“You make me feel nervous.” And guilty, even though she’d yet to do anything more reprehensible than sleeping with a man she did not love—or like.

He lifted her and set her down at the edge of the bed. “Unforgivable on my part. Let me offer my recompenses.”

He undid the sash on her dressing gown. She fought a renewed surge of panic. “Why are you nice to me?”

“I like you. I’m never unpleasant to people I like.”

“You are a high-minded man, are you not?”

“I do have some exacting standards.”

“As a man of exacting standards, can you justify to yourself why you like me, beyond that I am a source of naked pleasures?”

“You turned me down, and that speaks well of you—a man who went about it with as little finesse and forethought as I did deserved to be rebuffed. Other than that, you are right; I don’t have any firm foundations for approving of you. All the same, when you changed your mind, I was terribly flattered. So I am going to be unscientific and call this simply an affinity.”

Affinity. When in real life, he had the greatest antipathy for her.

“There is something else about you that I like,” he continued. She didn’t know when he’d pressed her into bed, but she lay with him beside her, her dressing gown completely open. Lightly he ran his hand over her breasts and her abdomen. “I like that I can make you forget, however briefly, everything that agitates you.”

He made love to her again. Afterward, when she began to deliberately bring her breathing under control, Christian knew that she’d left her sweet oblivion behind. This time, when she told him that she must go, he pulled on his trousers and helped her dress. Then he went out to the parlor and brought back her hat.

“What about your hair?” He’d discarded the pins and combs that had held together her coiffure. “I’ve scant knowledge on the repair of ladies’ hair.”

“I’ve the veil,” she said. “I’ll manage.”

Once her face was safely obscured behind the veil, he turned on the lamps and shrugged into his shirt.

“It’s late. I’ll walk you back.”

The light danced upon the warp and woof of her veil, which rippled just perceptibly as she exhaled. He had the feeling she was about to turn down his offer, but she said, “All right, thank you.”

A sensible woman, for he’d have insisted.

He remained in the bedroom. She walked slowly about the parlor, taking in the coffered ceiling, the stack of books on the writing desk, and the vase of red and yellow tulips on the mantel. For some reason he’d thought her dinner gown cream-colored, but it was apricot, the skirt spangled with beads and crystal drops.

He snapped his braces over his shoulders and tossed on a waistcoat and an evening coat. His cuff links, emblazoned with the Lexington coat of arms, were on the floor. He bent down and retrieved them.

As he straightened, he felt pinpricks upon his skin—the weight of her gaze. He glanced at her. She looked away immediately, even though he could see nothing but her faintly glimmering veil.

She did not trust him—or like him entirely, for that matter. And yet she’d let him seduce her—or was it the other way around?—twice. He could flatter himself and attribute the discrepancy to an intense attraction on her part, but years of training in objectivity made such delusions impossible.

He put on the cuff links. He even went to the trouble of a fresh necktie. If they were seen together at this hour, it might lead to certain suspicions, but he was not about to give concrete evidence by looking disheveled.

“Shall we?” He offered his arm.

She hesitated before laying her hand on his elbow. Still jittery, his baroness, almost as much as she’d been when she’d arrived in his suite. But questions to that regard set her on edge, so he refrained.

Instead, as they walked out of the suite, he asked, “Why were you celibate for so long? Clinging faithfully to the late baron’s memory?”

She made a sound that could only be termed snorting. “No.”

The Rhodesia was quiet except for the thrum of the mighty engine deep in its hull. The first-class passengers, whether asleep, seasick, or vigorously plugging away at their spouses, kept up the courtesy of decorous silence. The lamplit corridors might well have been those of a ghost ship.

“If you weren’t still mourning the baron, then I can’t imagine going so long without.”

“It is hardly unheard of.”

“True, but you don’t seem like someone who would want to be deprived for years upon years.”

Her sigh was one of impatience. “As much as this might amaze you, sir, a woman doesn’t always need a man to satisfy her. She can see to it herself with great competence.”

He chortled, delighted. “And you are, no doubt, tremendously capable in this respect?”

“I daresay I am sufficiently skilled from all that practice,” she said, rather grumpily.

He laughed again.

Even across the veil he could feel the glance she shot at him. “Are you always this cheerful afterward?”

“No, not at all.” His mood usually turned somber, sometimes downright dark—the women he slept with were never the one he wanted, whose hold over him remained unbreakable. But tonight he’d thought not once of Mrs. Easterbrook. “Are you always this testy afterward?”

“Maybe. I can’t remember.”

“Was the late baron a clumsy lover?”

“You’d like him to be, wouldn’t you?”

He’d never known himself to care whether a woman had had better or worse lovers than he. But in this instance, he found that, yes, he did have a preference. “Indeed. I’d like him to be thoroughly useless—impotent, if possible.”

He wanted to be the only one who’d ever brought her to peak after peak of shocking pleasure.

“Sorry to disappoint you. He might not have been Eros reborn, but he acquitted himself quite well.”

“How you thwart me, baroness.” A thought occurred to him. “So what was wrong with him?”

“I beg your pardon?”

“He was a decent lover, yet after his death, you resorted to your own … manual dexterity. And you did not dedicate your chastity to him. Was he unfaithful?”

She stopped. Not for long—she resumed her progress almost immediately, and at a faster pace. But he had his answer.

“He was a fool,” he declared.

She shrugged. “It was a long time ago.”

“Not all men are philanderers.”

“I know that. I have chosen to stay away from men not because I have lost faith in all of them, but because I am no longer confident of my ability to choose well.”

“I’m sorry.”

“Being unattached has its advantages.” Her face turned toward him. “At least I have been married. What is your excuse? Shouldn’t a man who holds a title as lofty as yours have produced an heir or two by now?”

He did not fail to notice she’d changed the subject. Deftly, too.

“Yes, he should. And I have no excuse, which is why I am on my way to a London Season, to do my duty.”

“You don’t sound very enthusiastic. You’ve no love for the idea of marriage?”

“I’ve nothing against the institution, but I suspect I shan’t be happy in it.”

“Why not?”

Again, her anonymity made him speak freely of things he would not even consider mentioning before others. “There is no question that I must marry—and soon. But I have little hope of finding a girl who will suit me.”

“You mean, no woman is good enough for you.”

“Quite the opposite. Other than my inheritance, I have very little to offer a woman. I’m hardly a dazzling conversationalist. I’d rather be in the field or locked in my study. And even when I am willing to linger in the drawing room and make small talk, I am not particularly easy to be around.”

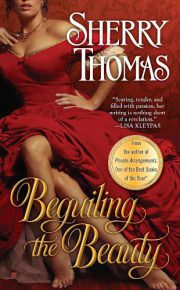

"Beguiling the Beauty" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Beguiling the Beauty". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Beguiling the Beauty" друзьям в соцсетях.