Darcy nodded slowly, trying to make sense his father’s words.

“Do you wish to know,” pursued the Ghost, “the weight and length of the chains you bear yourself? They are even, Fitzwilliam, even, identical in length to each other. However, I have come to warn you. If you persist along your present course…”

“What course?” interrupted Darcy.

“If you persist along your present course, your chain of iron will grow stronger and heavier, and the gold chain will vanish and your soul will have gone with it,” the ghost continued, “you then will be condemned to wander through the world for eternity. This is not a fate I would wish for you, my son.”

Darcy glanced about him on the floor, in the expectation of finding himself surrounded by fathoms of iron cable, but he could see nothing.

“Father,” he said, imploringly. “Father, tell me more. Speak comfort to me, Father.”

“I wish that I could, my son, but at the moment I have none to give,” the Ghost replied. “It comes from other regions, Fitzwilliam, and is conveyed by other ministers, to other kinds of men. Nor can I tell you what I would. A very little more is all that is permitted to me. I cannot stay; I cannot linger anymore.”

It was a habit with Darcy, whenever he became thoughtful, to fiddle with his signet ring. Pondering on what the Ghost had said, he did so now, but without lifting up his eyes to the specter.

The Ghost set up another cry and clanked its chain so hideously in the dead silence of the night.

“Many are captive, bound, and double-ironed,” cried the phantom, “yet they do not know! They do not know that no space of regret can make amends for one life’s opportunities missed!”

“Life’s opportunities missed,” faltered Darcy, who now began to apply this to himself. Could the Spirit be talking of Elizabeth?

Wringing its hands, the Ghost cried out, “Pemberley. The common welfare of its tenants—charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence—are all very easy at Pemberley. But elsewhere, Fitzwilliam? Have you shown these qualities elsewhere?”

“I try, sir,” Darcy replied, shaken.

“Did you try in Hertfordshire? Did you show charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence there, Fitzwilliam?” Darcy was forced to shake his head, for he had not.

The spirit held up the iron chain and flung it down heavily.

“Hear me!” cried the Ghost. “My time is nearly gone.”

“I will,” said Darcy. “But do not be too hard upon me, Father!”

“How it is that I appear before you in a shape that you can see, I may not tell. I have sat invisible beside you many and many a day.”

It was an agreeable idea. Darcy had often wished for his father’s advice when making decisions.

“That is no light part of my penance,” pursued the Ghost. “I have been watching you come to this precipice, and I am aware that part of it is my own doing and I must suffer for it. As a child, I taught you what was right, but I did not teach you to correct your temper. I gave you good principles but left you to follow them in pride and conceit. Unfortunately, as my only son—for many years my only child—I spoilt you; allowed, encouraged, almost taught you to be selfish and overbearing; to care for none beyond your own family circle; to think meanly of all the rest of the world; to think meanly of their sense and worth compared with your own. That is why I wear this heavy chain. I am here tonight to warn you that you have yet a chance and hope of escaping your fate. A chance and hope not just of my procuring, Fitzwilliam, but of others’, who also have your welfare at heart.”

“You are too harsh in your own criticism. You were always a good father,” said Darcy. “Thank you, for I do not believe that I said it during your life!”

“You will be haunted,” resumed the Ghost, “by Three Spirits, all of whom will appear familiar to you, for that is their way.”

Darcy’s countenance fell almost as low as the Ghost’s had done.

“Is that the chance and hope you mentioned, Father?” he questioned in a faltering voice.

“It is.”

“I—I think I would rather not,” said Darcy.

“Without their visits,” said the Ghost, “you cannot hope to shun the path you now tread. Expect the first tomorrow, when the bell tolls one.”

“Could I not take them all at once and have it over, Father?” hinted Darcy.

“Expect the second on the next night at the same hour. The third upon the next night when the last stroke of twelve has ceased to vibrate. Look to see me no more; and for your own sake, remember what has passed between us.”

When it had said these words, the specter took its wrapper from the table and bound it round its head, as before. Darcy knew this, by the smart sound its teeth made, when the bandage brought the jaws together. He ventured to raise his eyes again, and found his supernatural visitor confronting him in an erect attitude, with its chain wound over and about its arms.

The apparition walked backward from him; and at every step it took, the window raised itself a little, so that when the specter reached it, it was wide open.

It beckoned Darcy to approach, which he did. When they were within two paces of each other, Old Mr. Darcy’s Ghost held up its hand, warning him to come no nearer. Darcy stopped, not so much in obedience as in surprise and fear, for on the raising of the hand, he became sensible of confused noises in the air: incoherent sounds of lamentation and regret, wailings inexpressibly sorrowful and self-accusatory. The specter, after listening for a moment, joined in the mournful dirge and floated out upon the bleak, dark night. “Hear them, Fitzwilliam! Listen to their cries, for any one of them could be you!” said Old Mr. Darcy. “Look upon them!”

Darcy followed to the window, desperate in his curiosity. He looked out.

The air was filled with phantoms, wandering hither and thither in restless haste and moaning as they went. Every one of them wore chains like Old Mr. Darcy’s Ghost; some few were covered completely in chains. Darcy had personally known many during their lifetime. He had been quite familiar with one old ghost, in a white waistcoat, with a monstrous iron chain attached to its ankle, who cried piteously at being unable to assist a wretched woman with an infant, whom it saw below, upon a doorstep. The misery with them all was, clearly, that they sought to interfere, for good, in human matters, and had forever lost the power to do so.

Whether these creatures faded into mist or mist enshrouded them, he could not tell. But they and their spirit voices faded together; and the night became as it had been when he walked home.

Darcy closed the window and examined the door by which the Ghost had entered. It was locked, as he had locked it with his own hands, and the bolts were undisturbed. He tried to say “Humbug!” but stopped at the first syllable. And being, from the emotion he had undergone, or the fatigues of the day, or his glimpse of the Invisible World, or the conversation of the Ghost, or the lateness of the hour, much in need of repose, he went straight to bed, without undressing, and fell asleep upon the instant.

Chapter 2

Christmas Past

When Darcy awoke, it was so dark, that looking out of the bed, he could scarcely distinguish the transparent window from the opaque walls of his chamber. He was endeavoring to pierce the darkness with his eyes when the chimes of a neighboring church struck the four quarters, so he listened for the hour.

To his great astonishment, the heavy bell went on from six to seven, and from seven to eight, and regularly up to twelve, then stopped. Twelve! It was past two when he went to bed. The clock was wrong. An icicle must have gotten into the works. Twelve!

He glanced at the clock that rested on the mantel. Its rapid little pulse beat twelve and stopped.

“Why, it is not possible,” said Darcy, “that I can have slept through a whole day and far into another night. It is not possible that anything has happened to the sun and this is twelve at noon!”

The idea being such an alarming one, he scrambled out of bed and groped his way to the window. He was obliged to rub the frost off with the sleeve of his dressing gown before he could see anything, and even after that could see very little. All he could make out was that it was still very foggy and extremely cold. It was a great relief that there was no noise of people running to and fro or making a great stir, as there unquestionably would have been if night had beaten off day and taken possession of the world.

Darcy went to bed again, thought about it over and over, and could make nothing of it. The more he thought, the more perplexed he was; and the more he endeavored not to think, the more he thought of his father’s Ghost. It bothered him exceedingly. Every time he resolved within himself, after much mature inquiry, that it had all been a dream, his mind flew back to its first position, and presented the same problem to be worked through: Was it a dream or not?

Ding, dong!

“A quarter past,” said Darcy counting.

Ding, dong!

“Half past!” said Darcy.

Ding, dong!

“A quarter to it.” Darcy suddenly remembered that the Ghost had warned him of a visitation when the bell tolled one. He resolved to lie awake until the hour was past; and, considering that he could no more go to sleep than go to Heaven, this was perhaps the wisest resolution in his power.

The quarter was so long that he was more than once convinced he must have sunk into a doze unconsciously and missed the clock. At length it broke upon his listening ear.

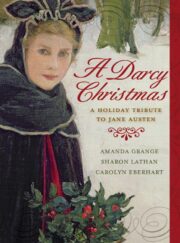

"A Darcy Christmas" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Darcy Christmas". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Darcy Christmas" друзьям в соцсетях.