George Darcy’s face was before him. It was not in impenetrable shadow, as the other objects in the yard were, but had a cheerful light about it. It was not angry or ferocious, but looked at Darcy as his father often used to look: with ghostly spectacles turned up upon its ghostly forehead. The hair was curiously stirred, as if by breath or hot air and, though the eyes were wide open, they were perfectly motionless. That, and its livid color, made it horrible; but its horror seemed to be in spite of the face and beyond its control, rather than a part of its own expression.

As Darcy looked fixedly at this phenomenon, it was a knocker again. He blinked and then traced the lion’s head with fingers, feeling only cold iron beneath them. To say that he was not startled or that his blood was not conscious of a terrible sensation to which it had been a stranger from infancy would be untrue. Shaking his head, he put his hand upon the key he had relinquished, turned it sturdily, walked in, and lighted the candle that was waiting for him.

He did pause, with a moment’s irresolution, before he shut the door. He did look cautiously behind it first, as if he half expected to be terrified with the sight of Old Mr. Darcy’s backside sticking out into the hall. But there was nothing on the back of the door, except the screws and nuts that held the knocker on, so he closed it with a bang.

The sound resounded through the house like thunder. Every room above and every cask in the cellars below appeared to have a separate peal of echoes all its own. Darcy was not a man to be frightened by echoes. He fastened the door and walked across the hall and up the stairs, slowly too, for his candle cast eerie shadows as he went.

There was plenty of width to the old flight of stairs—a coach-and-six could drive up it with room to spare. A hearse also could have done it easily enough, which is perhaps the reason why Darcy thought he saw a locomotive hearse going on before him in the gloom.

Up Darcy went, wondering if he perhaps he was drunk. He had not thought so, for he had never truly overindulged. Yet it could explain the strange tricks his eyes were playing on him. Yet before he shut his heavy door, he walked through his rooms, which had once been occupied by his deceased parent, to see that all was right. He had just enough recollection of the face to desire to do that.

They were a cheerful suite of rooms, consisting of a sitting room and bedroom, and each was as it should be. The logs were at the ready, which Darcy quickly ignited into a large fire in the grate; the pitcher and basin were ready for use; and the decanter of brandy was upon the table, just as his valet left it before he and the rest of the servants quit the house to visit their own families and friends for the evening’s celebrations. Nobody was behind the curtains; nobody was underneath the sofa; nobody was under the bed; nobody was in the closet; nobody was in his dressing gown, which was hanging up in a suspicious attitude against the wall.

Quite satisfied, he closed his door and locked himself in, which was not his custom. Thus secured against surprise, he took off his cravat and jacket, leaving his waistcoat on but unbuttoned, and shrugged into the dressing gown before sitting down in front of the fire to take his glass of brandy.

It was a very good fire indeed, nothing to it on such a bitter night. He sat close to it and brooded; the brandy remained untouched. The fireplace was an old one, built long ago, and carved all round with designs to illustrate the Scriptures. There were hundreds of figures to attract his thoughts; and yet only the face of his father, five years dead, remained in Darcy’s thoughts.

“Nonsense!” said Darcy, and walked across the room. After several turns, he sat down again. As he threw his head back in the chair, his glance happened to rest upon a bell, which hung in the room and communicated to the servants in the highest story of the building. It was with great astonishment, and with a strange, inexplicable dread, that as he looked, he saw this bell begin to swing. It swung so softly in the outset that it scarcely made a sound; but soon it rang out loudly, and so did every bell in the house.

This might have lasted half a minute or a minute, but it seemed an hour. The bells ceased as they had begun: together. They were succeeded by a clanking noise, deep down below, as if some person were dragging a heavy chain over the casks in the cellar. Darcy then remembered having heard that ghosts in haunted houses were described as dragging chains.

The cellar door flew open with a booming sound, and then he heard the noise much louder, on the floors below; then coming up the stairs; then coming straight towards his door.

“It is nonsense still!” said Darcy. “I will not believe it.”

His color changed though, when, without a pause, it came on through the heavy door and passed into the room before his eyes. Upon its coming in, the flames leaped up and just as quickly fell again.

His Father’s ghost! The same face, the very same. George Darcy in his favorite jacket, usual waistcoat, breeches, and boots. The chains he drew were clasped about his middle. One was very long and was made (for Darcy observed it closely) of gold studded with precious gems while the other was shorter, hardly seeming to clasp about his waist and was wrought in thick iron. His body was transparent, so that Darcy, observing him and looking through his waistcoat, could see the two buttons on his coat behind.

No, he did not believe it, even now. Though he looked the phantom through and through, and saw it standing before him; though he felt the chilling influence of its death-cold eyes and marked the very texture of the folded kerchief bound about its head and chin, which wrapper he had not observed before; he was still incredulous and fought against his senses.

“What do you want with me?” inquired Darcy

“Much!” George Darcy’s voice, no doubt about it.

“Who are you?” Darcy demanded, knowing the answer but feeling compelled to ask anyway.

The ghost raised a quizzical eyebrow, “Ask me who I was.”

“Who were you then?” asked Darcy.

“In life I was your father, George Darcy.”

“Can you—can you sit down?” Darcy asked the question because he didn’t know whether a ghost so transparent might find himself in a condition to take a chair and felt that in the event of its being impossible, it might involve the necessity of an embarrassing explanation.

“I can.”

“Please do so then, sir,” said Darcy, looking doubtfully at him.

The ghost sat down on the opposite side of the fireplace, as if he were quite used to it. “You do not believe in me,” observed the Ghost.

“I do not,” said Darcy.

“What evidence would you have of my reality beyond that of your senses?”

“I do not know,” said Darcy.

“Why do you doubt your senses?”

“Because,” said Darcy, “alcohol affects them. I do not usually indulge in the grape as much as I did this evening. I am sure there is more of the cask than of the casket about you, whatever you are!”

Darcy was not much in the habit of cracking jokes, nor did he feel, in his heart, by any means waggish then. The truth is that he tried to be smart, as a means of distracting his own attention and keeping down his terror, for the specter’s voice disturbed the very marrow in his bones.

To sit, staring at those fixed, glazed eyes, in silence for a moment, would play, Darcy felt, the very deuce with him. It was as if he again were but twelve years old and about to be punished for some childish misdeed. There was something very awful too in the specter’s being provided with an infernal atmosphere of its own.

At this, the Spirit raised a frightful cry and shook its chain with such a dismal and appalling noise that Darcy held on tight to his chair, to save himself from falling off of it. But how much greater was his horror, when the phantom took off the bandage round its head, as if it were too warm to wear indoors, and its lower jaw dropped down upon its breast!

Darcy placed his elbows on his knees, and clasped his face in his hands, as if to banish the specter. There was silence in the room, but Darcy could still feel the Spirit.

Glancing up, he looked at the Spirit, whose jaw was again shut. “Father!” he asked. “Why do you trouble me?”

“Fitzwilliam!” replied the Ghost. “Do you believe in me or not?”

“I do,” said Darcy. “I must. Why are you here? Why do you come to me?”

“It is required of every man,” the Ghost returned, “that the Spirit within him should walk abroad among his fellow-men, and travel far and wide; and if that spirit goes not forth in life, it is condemned to do so after death. It is doomed to wander through the world and witness what it cannot share, but might have shared on earth and turned to happiness! And, my son, you are in danger of losing your spirit within.”

Again the specter raised a cry and shook its chain, and wrung its shadowy hands.

“You wear chains,” said Darcy, trembling. “Tell me why?”

“I wear the chains I forged in life,” replied the Ghost. “I made them link by link, and yard by yard; the gold, for all its length, is of no weight, for it is forged from the good I did during my life. However, this bit”—the Spirit touched the metal belt around his waist—“this bit of forged iron weighs heavily. For it is forged from those times when I acted without consideration for others and thought only of myself. Those times when I let pride and conceit bar the way to doing what is proper and just. I girded them on of my own free will, and of my own free will I wore it.”

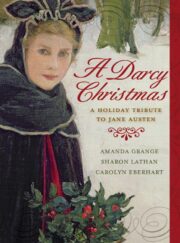

"A Darcy Christmas" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "A Darcy Christmas". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "A Darcy Christmas" друзьям в соцсетях.