I picked up the toy and tucked it back in the crib beside her. Ignoring it altogether she beamed up at my face and her legs and arms went into a little frenzy of kicks to welcome me. She gurgled loudly; she reached for me. I chuckled; she was irresistible. No wonder the entire household was demented over her smiles. She was as much of a domestic tyrant as I could ever be. We were much alike, this little baby and I.

I bent to smile at her, before I left her and went back to my study, and flicked her cheek with one careless finger. She caught it with a surprisingly strong grasp and guided it unerringly towards her smiling, toothless mouth. The little gums closed on it and the cheeks hollowed as she sucked vigorously, her eyes hazy blue with delight. I chuckled; the child was an utter sensualist, like myself. And she grabbed her pleasures, like I do, with a firm grip. When I tried to pull away she hung on and was half lifted from the cradle before I relented and scooped her up and placed her against my neck.

She smelled so sweet. That delicious baby smell of warm clean skin and soap. That sweet smell lingering around their mouths from drinking only warm milk. That lovely clean smell of newly laundered cotton and newly washed best wool. I tucked her little head securely into my shoulder and swayed a little. Her coos of pleasure started again, resonant by my ear, and when I turned my face to sniff the warm little crease of her plump neck she made me laugh aloud by suddenly fixing her mouth on to my jaw line, like a little vampire, and sucking noisily and with evident satisfaction.

The smile still on my face, my feet still dancing to jiggle her, I turned towards the house. Someone was in the parlour window watching me. It was Celia. She stood utterly still, her face like white marble.

My face was still warm with laughter and affection for the little baby, but as I met her eyes the smile died from me and I felt uneasy and guilty — as guilty as if she had caught me with my hands in her lace drawer, or if she had found me reading her letters. She disappeared and a few seconds later the front door opened and she came out on to the terrace.

Her hands were trembling but her face was set and her walk was swift and direct. She came to me without a word, and lifted the baby from the warmth of my neck with as much emotion as if she were taking a scarf off me.

‘I put Julia out for her sleep,’ she said unemotionally. She turned her back to me and placed Julia in the cradle. Disappointed, the child started a wail of protest, but Celia tucked her in as firmly as any strict nurse.

‘I would rather she were not disturbed when she should be having her rest,’ said Celia.

I felt as awkward as a boy in an apple orchard.

‘Of course, Celia,’ I said deferentially. ‘She dropped her toy and I merely came out to give it back to her.’

Celia straightened up and turned to me. ‘She would be happy to play that game all afternoon,’ she said. ‘But you, I am sure, have work to do.’

I was dismissed. Little insignificant Celia, standing tall with the power of her motherhood over the child, had dismissed me like an unreliable maid.

‘Of course,’ I said, and I smiled like an idiot. ‘Of course.’ And I turned on my heel and went back down the terrace to where my office window stood open and my desk waited, piled with papers. In the length of that short, awkward walk, I could feel Celia’s eyes on my back, Celia watching me with no affection in her gaze.

I should have learned from that, I suppose. But Julia drew me. A little, only a little. I had no great longing for her. When I occasionally heard her cry out in the night I slept better for my deep contentment that it was not me who had to get up to see to her. When she was fretting during the day, or when Celia missed supper and the tea tray because she was up in the nursery, I felt no instinct then to be with the baby. But sometimes — when the weather was hot and I could see her little legs kicking and hear her cooing — I would slink out to the terrace like a clandestine lover and smile at her, and tickle her plump little palms and feet.

I learned discretion. Celia never again caught me hanging over the cradle. But when she went to Chichester with Harry to choose some new hangings for the nursery, and Mama lay down feeling unwell because of the heat, I spent an easy, laughter-filled half-hour playing peep-bo with the baby, dodging round her sunshade and appearing as if by magic on one side of the cradle and then the other, which made her gurgle with laughter so much she nearly choked herself.

Predictably, I tired of the game long before she did. Besides I had to drive down to the village to see the smith. She gripped my face when I kissed her goodbye, but when I actually disappeared she set up such a howl of protest that her nurse came bustling out of the house to see what was wrong.

‘She won’t settle now,’ she said, eyeing me with disfavour. ‘She’s all awake and playful now.’

‘It’s my fault,’ I confessed. ‘What would settle her down?’

‘I shall have to rock her,’ said the nurse, grudgingly. ‘The movement of the cradle might do it.’

‘I have to drive to the village,’ I offered. ‘Would she fall asleep in the carriage?’

The nurse’s face brightened at once at the prospect of an airing in my smart curricle and she bustled off to get her bonnet and an extra shawl for Julia.

I had been right. As soon as she was lifted from the cradle, Julia beamed her approval and started her delightful coos of pleasure. And when we trotted down the drive with the bars of sunlight and shade from the roof of trees flickering in her eyes she waved her little hands to greet the wind and the sound of trotting hoofs and the brightness and rush and beauty of it all.

I slowed down on the bridge over the Fenny.

‘This is the Fenny,’ I told her solemnly. ‘When you are a big girl I shall teach you how to tickle for trout here. Your papa can teach you how to use a rod and line like a lady, but I shall teach you how to tickle them and flick them out on the bank like a proper country child.’

She beamed at me as if she understood every word, and I beamed back in mutual approval. Then I clicked to Sorrel and we trotted past the lodge gates where Sarah waved to us and out down the sunny lane to Acre.

‘These are the meadowlands, resting this year,’ I told Julia, gesturing with my whip. ‘I think good fields should be rested every three years and grow just grass. Your papa thinks they should be rested every five. You can be the judge of that for we have rested some for three years and some for five, and when you are a lady, farming the land like me, you can be the judge of which system kept the land in the greatest heart.’

Julia’s little sun bonnet nodded gravely as if she could understand every word. But I think she may have caught the inflexion of my voice and heard my tones of love for the land, and of a growing tenderness for her.

Half-a-dozen people were outside the smithy when I drew up, villagers and one fanner tenant waiting for his work-horse to be shod. The women were around the curricle in a second, admiring the pretty baby and the exquisite lace dress. I tossed the reins to the smith, who came out, wiping grimy hands on his leather apron, and passed the baby carefully down to the village women.

They cooed over her, as maternal as broody hens; they touched her lace petticoats and her fleecy shawl and they stood in line so that each might hold her and admire the smoothness of her skin, the blueness of her eyes and the utter whiteness of her clothes.

By the time I had finished with the smith, she had reached the end of the line, a little dishevelled but none the worse for being handed round like some sacred relic.

‘Better change her before her mama gets back,’ I said ruefully to her nurse, noting the lace trimming on her little gown was grey where it had been fingered by hands ingrained with years of dirt.

‘Indeed, yes,’ said Nurse stiffly. ‘Lady Lacey has never taken her to the village and would never have let those people touch her.’

I glanced sharply at her, but I said nothing for a moment.

‘She’s taken no harm,’ I said eventually. ‘Have you, little girl? And these people will be your people, as they are mine. These are the people who make the money that keeps Wideacre prosperous and beautiful. They are dirty so that we can have daily baths and fine clean clothes. You must always be ready with a smile for them, little one. You belong to each other.’

I drove in silence then, enjoying the wind in my face and keeping a careful eye on the road ahead to make sure we struck no stones which might jog her. I was driving so carefully I hardly heard the noise of a carriage and pair and I jumped like a criminal when I suddenly saw, in the road ahead of us, the family chaise. They were just ready to turn into the lodge gate; another second earlier and I might have been home before them. As it was, Celia, gazing out of the offside window, had a perfect view of my curricle trotting briskly down the lane from Acre, with her nurse and her child sitting up bold as brass in the passenger seat.

Her eyes met mine and her face was blank. I knew she was angry and I felt no surprise. I had a sinking feeling in my gut, the like of which I had not felt since I was a child in disgrace with my papa. I had never thought Celia capable of rages. But to take her child out for a drive without permission was, I knew, something she would regard as wrong. And faced with that icy stare I felt extremely guilty.

I did not hurry to follow them up the drive, but there was no enraged mother waiting for me in the stable yard. Nurse and Julia dismounted and went into the house by the west-wing door, to slink up to the nursery for a total change of clothes, I guessed. I handed Sorrel over to the groom and went round to the front door. Celia was waiting for me in the hall and she drew me into the parlour. Harry, discreetly, perhaps obediently, was nowhere to be seen.

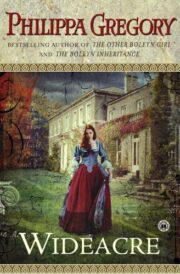

"Wideacre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Wideacre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Wideacre" друзьям в соцсетях.