‘Are you feeling better?’ she asked sweetly. I drew her hand under my arm as we walked up the steps.

‘I am so much better,’ I said, confidentially. ‘And I have something to tell you, Celia, and I need your help. Come to my room and we can talk before dinner.’

‘Of course,’ said Celia, willing and flattered. ‘But what do you need to tell me? You know I will help you in any way I can, Beatrice.’

I smiled lovingly at her, and stepped back gracefully to let her precede me into the hotel. After all, what was one gesture of precedence now, when I should, with her loyal and generous assistance, displace her, and any child of hers, for ever?

As soon as I had shut the door to my bedroom I composed my face into a solemn expression, drew Celia down beside me on a chaise-longue and put my hand in hers. I turned a sad, sweet gaze on her and felt my green cat’s eyes fill with tears as I said, ‘Celia, I am in the most dreadful trouble, and I know not which way to turn.’

Her brown eyes widened and the colour went from her cheeks.

‘I am ruined, Celia,’ I said with a sob, and I buried my face in her neck and felt the shudder that ran through her.

‘I am,’ I said, keeping my face down. ‘Celia, I am with child.’

She gasped and froze. I could feel every muscle in her body tense with shock and horror. Then she determinedly turned my face up so she could look into my eyes.

‘Beatrice, are you sure?’ she asked.

‘Yes,’ I said, looking as aghast as she. ‘Yes, I am sure. Oh, Celia! Whatever shall I do?’

Her lips trembled, and she put out her hands to cup my face.

‘Whatever happens,’ she said, ‘I shall be your friend.’

Then we were silent while she digested the news.

‘The baby’s father …?’ she said diffidently.

‘I don’t know,’ I said, choosing the safest lie. ‘Do you remember on the day I rode over to you to fit my gown I was taken ill at Havering Hall?’

Celia nodded, her honest eyes on my face.

‘I felt faint on the ride over and had to dismount; I must have swooned and when I awoke, a gentleman was reviving me. My dress was disordered — you may remember a tear on my collar … but I did not know … I could not tell …’ My voice was a strained whisper, almost silenced by tears and shame. ‘He must have dishonoured me while I was unconscious.’

Celia clasped her hands around mine.

‘Did you know him, Beatrice? Would you recognize him again?’

‘No,’ I said, disposing of the happy ending summarily. ‘I had never seen him before. He was in a travelling curricle with luggage strapped on the back. Perhaps he was driving through Acre on his way to London.’

‘Oh, God,’ said Celia, despairingly. ‘My poor darling.’

A sob stopped her from speaking, and we sat with our arms around each other, our wet cheeks touching. I reflected sourly that only a bride bred on tales from the romances and then raped once and left alone would swallow such a faradiddle. But by the time Celia was experienced enough to doubt conception while unconscious, she would be too well encased in my lie to be able to withdraw.

‘What can we do, Beatrice?’ she said, despairingly.

‘I shall think of something,’ I said bravely. ‘Don’t you grieve now, Celia. Go and change for dinner and we will talk more tomorrow when we have had time to think.’

Celia obediently went. But she paused by the door.

‘Will you tell Harry?’ she asked.

I shook my head slowly. ‘He could not bear the thought of me sullied, Celia. You know how he is. He would hunt for that man, that devil, all around England, and not rest until he had killed him. I hope to find some way to keep this great trouble quite secret, between you and me alone. I put my honour in your hands, Celia, dear.’

She would not need telling twice. She came back into the room and kissed me, to assure me of her discretion. Then finally she took herself off, closing the door behind her as softly as if I was an invalid.

I sat up and smiled at my reflection in the glass of the pretty French-style dressing table. I had never looked better. The changes in my body might have made me feel ill, but had done nothing but good for my looks. My breasts were fuller and more voluptuous, and they pressed against my maiden gowns in a way that filled Harry with perpetual desire. My waist was thicker but still trim. My cheeks flushed with a new warmth, and my eyes shone. Now I was back in control of events I felt well. For now I was not a foolish whore encumbered with a bastard, but a proud woman carrying the future Master of Wideacre.

The following day, as we sat and sewed in the sunny parlour of the hotel, Celia wasted no time in returning to our problem. I was fiddling around, supposedly hemming lace that was to be sent home to Mama on the next packet — though I could not help suspecting she would have to wait a long time if she waited for my hemming. Celia was industriously busy: cutting broderie anglaise from a genuine Bordeaux pattern.

‘I have worried all night, but I could think of only one solution,’ Celia said. I glanced at her quickly. There were dark shadows under her eyes. I could believe she had hardly slept at all for worry at my pregnancy. I had hardly slept either, but that was because Harry had woken me at midnight with hard desire, and then again in the early hours of dawn. We could hardly have enough of each other, and I shuddered with perverse pleasure at the thought of Harry’s seed and Harry’s child inside me at once. And I smiled secretly at the thought of how I had gripped Harry’s hips to prevent him plunging too hard inside me, guarding the child who deserved my protection.

And while I was lovemaking with her husband, Celia, dear Celia, was worrying over me.

‘I can think of only one solution,’ Celia said again. ‘Unless you wish to confide in your mama — and I shall understand if you do not, my dear — then you will need to be away from home for the next few months.’ I nodded. Celia’s quick wits were saving me a lot of troublesome persuasion.

‘I thought’, Celia said tentatively, ‘that if you were to say you were ill and needed my company, then we could go to some quiet town, perhaps by the sea, or perhaps one of the spa towns, and we could find some good woman there to care for you during your confinement, and to take the baby when it is born.’

I nodded, but without much enthusiasm.

‘How kind you are, Celia,’ I said gratefully. ‘Would you really help me so?’

‘Oh, yes,’ she said generously. I noted with amusement that six weeks into marriage and she was ready to deceive and lie to her husband without a second’s hesitation.

‘One thing troubles me in that plan,’ I said. ‘That is the fate of the poor little innocent. I have heard that many of these women are not as kindly as they seem. I have heard that they ill-treat or even murder their charges. And although the child was conceived under such circumstances as to make me hate it, it is innocent, Celia. Think of the poor little thing, perhaps a pretty baby girl, a little English girl, growing up far away from any family or friends, quite alone and unprotected.’

Celia laid down her work with tears in her eyes.

‘Oh, poor child! Yes!’ she said. I knew the thought of a lonely childhood would distress her. It struck chords with her own experience.

‘I can hardly bear to think of my child, your niece, Celia, growing up, perhaps among some rough, unkind people, without a friend in the world,’ I said.

Celia’s tears spilled over. ‘Oh, it seems so wrong that she should not be with us!’ she said impulsively. ‘You are right, Beatrice, she should not be far away. She should be near so we can watch over her well-being. If only there was some way we could place her in the village.’

‘Oh!’ I threw up my hands in convincing horror. ‘In that village! One might as well announce it in the newspapers. If we really wish to care for her, to bring her up as a lady, the only place for her would be at Wideacre. If only we could pretend she was an orphan relation of yours, or something.’

‘Yes,’ said Celia. ‘Except that Mama would know that it was not true …’ She fell silent and I gave her a few minutes to think around the idea. Then I planted the seed of my plan in her worrying little mind.

‘If only it were you expecting a child, Celia!’ I said longingly. ‘Everyone would be so pleased with you, especially Harry! Harry would never trouble you with your … wifely duty … and the child could look forward to the best of lives. If only it were your little girl, Celia …’

She gasped, and I sighed silently with a flood of secret relief and joy. I had done it.

‘Beatrice, I have had such an idea!’ she said, half stammering with excitement. ‘Why don’t we say it is me who is expecting a baby, and then say it is my baby? The little dear can live safely with us, and I shall care for her as if she were my own. No one need ever know that she is not. I should be so happy to have a child to care for and you will be saved! What do you think? Could it work?’

I gasped in amazement at her daring. ‘Celia! What an idea!’ I said, stunned. ‘I suppose it could work. We could stay here until the child is born and then bring her home. We could say she was conceived in Paris and born a month early! But would you really want the poor little thing? Perhaps it would be better to let some old woman take her?’

Celia was emphatic. ‘No. I love babies and I should especially love yours, Beatrice. And when I have children of my own she shall be their playmate, my eldest child and as well loved as my own. And she will never, never know she is not my daughter.’ Her voice quavered on a sob, and I knew she was thinking of her own girlhood as the outsider in the Havering nursery.

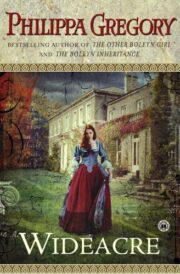

"Wideacre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Wideacre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Wideacre" друзьям в соцсетях.