‘Oh, no!’ she said. ‘But …’

‘That’s enough!’ said Harry, with a bully’s abruptness. ‘Beatrice is running the land as we see fit. And I shall go harvesting another year, when Acre has come out of this fit of the sullens. This conversation is closed.’

Celia dropped her eyes to the coffee jug and I saw a single tear fall like a raindrop on to the silver tray. But she said nothing. And John, after one compassionate glance at her downcast face, said nothing more. I waited until I was sure they were completely silenced and then I went back to my office. I had work to do.

At last the prospects seemed to be brightening. The fields were being cut faster than ever before and I was out every day in a fever of impatience to get the job done.

Not only could I see the chance of a great bounty on the way for Wideacre, and a chance to be free, utterly free, of the creditors but I also felt a storm in the air. It prickled on the horizon. I felt it on my skin. The skies were clear, I could not wish for clearer. But I could feel the clouds massing against me, somewhere over the horizon.

The days were hot, too hot. They had lost their honest summertime heat and were sultry, threatening. Tobermory’s neck was streaked with sweat even while he stood in the shade and the flies buzzed ominously low about his head. The men in the field suffered as it became hotter and damper. One day a reaper fainted — Joe Smith, old Giles’s son. He fell on his sickle like a fool and the line broke as they ran around him. I rode over. It was a nasty wound, open nearly to the bone.

‘I’ll send for the Chichester surgeon,’ I said generously. ‘Margery Thompson can bind it up for now, and I will send for the doctor to stitch it for you.’

Joe looked up at me, white with shock, his dark eyes hazy.

‘I’d rather have Dr MacAndrew if I may, Miss Beatrice,’ he said humbly.

‘Get in the wagon then,’ I said with sudden temper. ‘It’s going up to the Hall. I think your beloved Dr MacAndrew is in. If he’s out doing good deeds in Acre you can sit in the stable yard and wait for him. I hope you don’t bleed to death while you are waiting.’

And I wheeled Tobermory and trotted back to my patch of shade by the hedge, and watched them help Joe into the wagon. He was in luck, John was in the garden and saw him as soon as the wagon drew up in the stable yard. He treated him for free and with such skill that Joe was out gleaning two days later. Another proof of John’s skill. Another reason for them to love him. Another enemy of mine.

I was surrounded by them. I worked all day in a field full of men who hated me and women who feared me. I slept at night with only a door between me and a man who wished for my death. And I woke every dawn to know that somewhere, out on the downs, was another enemy who was planning my death, who was readying himself to come for me.

The weather seemed to hate me. The heat held but there was no wind. The wheat barely rustled before it was cut down. In the hot humid days there was utter silence. The men did not talk in the fields; the women did not sing. Even the little children, twisting the stalks for tying the stooks, played and spoke in whispers. And if I rode Tobermory over towards them, they backed away with silent mouths agape, black stubs of teeth showing, and melted, like diseased fox cubs, into the hedgerow.

Not even the birds sang in the heat. You would think they shared Wideacre’s baking despair and were silent for sorrow. Only in the cool ominous dawns and in the uneasy twilight would they start up and their voices sounded eerie, like the whine of a whipped dog.

The light seemed wrong to me, as well. I was coming half to believe that it was my eyes and senses that were deceiving me, tricking me into fearing a storm when I so desperately needed a settled calm. But if I had mistrusted the prickle down my sweaty spine, and the wet smell of the heavy air, I could not be wrong over the brightness of the day. It stung my eyes. It was not the brightest honest yellow heat of a Wideacre midsummer, but something with a sickly dark core. A bluish light, a purple light hung over us. A sun like a red wound in a yellowing sky. When I opened my eyes in the morning I shuddered instinctively as if I had a fever. I dressed in my hot full-skirted habit with no joy. The sky was like an oven above me, and the ground as hard as iron beneath my feet, all the moisture baked from it. The Fenny was shrunk so small I could not hear its ripple from my bedroom window, and when it flowed through Acre it stank with the slops thrown into it, and the cattle fouling it. I too felt desiccated: as dry as an old leaf, or an empty seashell when the smooth little wet animal that lived inside it is dead.

So I hurried the reapers. I was there first in the field every morning, and last to leave every night. I rode them as I would a sluggish horse and they would have kicked out if they had dared. But they could not. Whenever they halted the line to wipe their heads or to rub the stinging sweat from their eyes they would hear me call, ‘Reapers, keep moving!’ And they would groan and grasp the handle of the sickle — slick with sweat and turning painfully even in their callused hands. They did not murmur against me. They had not even breath enough to curse me. They worked as if they just longed for the whole miserable job to be done, the harvest in, and winter to bring cold starvation and quick death to end it all.

And I sat high on the sweating horse, my face white and strained beneath the cap that cast no shade on my eyes, and knew that longing for myself. I was bone-weary. Tired with days and days of watching and worrying and driving them, and driving myself. And tired with a deep inner sickness that said to me as slowly and as firmly as a funeral bell, ‘All for nothing. All for nothing,’ as if the words made any sense at all.

But we were nearly done. The stocks were piled in the centre of the field awaiting the wagons, and the men had collapsed, gasping in the airless shade of the hedge. The women and the old people stacking the stooks were nearly finished, and the men watched their bent-backed wives and parents with lack-lustre beaten eyes, without the strength to help them.

Margery Thompson, who had been at the vicarage when John saved Richard’s life, had ceased her work already. I watched her under my eyelashes, my attention suddenly sharpened with unease. She had seated herself on the bank by the hedge and was twisting stalks of corn on her lap. It is the tradition on Wideacre that the last stook, the last one of the whole harvest, is a corn-baby, a corn-dolly. Woven by the cleverest old woman, the doll represents the leader of the harvest. Season after season I had loaned my ribbons to make the circle of magic between the harvest and me complete. I had seen a little corn-dolly Beatrice triumphant at the top of the pile of stooks. In the year Harry brought in the harvest the corn-dolly was bawdy, with a scrap of linen for its shirt and a head of wheat between the stalk legs, grotesquely erect, and everyone had roared. Harry had taken that one home, grinning, and hid it from Mama. The corn-dollies they had made for me were pinned on the wall of my office. Proof, if ever I was near forgetting, that the world of papers and debts and business was the pretend life, and the real world was the corn and the goddesses of the fertile earth.

The corn-dolly tradition had slipped from my worried, money-mad mind, but as I watched the old woman’s nimble fingers moving so cleverly and so quickly among the stalks I knew a twinge of dread warning me of some fresh disaster, that some magic against me was brewing.

The clouds had come out from hiding at last and were piling up on the horizon like great walls, blocking out the eerie sunlight and making a premature dusk. It had held off long enough to save me. As long as the wagons came safely through, and took Wideacre’s corn to the richest market in the world, the rain could pour down and wash Acre and all Wideacre into the Fenny for all I cared. I had done what I set out to do, and I cared little if the storm drowned me.

Tobermory shivered in the breeze, not because it was cold, for it carried no freshness, but it blew like the breath of a threat. It was as hot as if it blew from India with the black magic of distant dangerous places. Margery Thompson had the corn-dolly on her lap and was muttering to it as if she were nursing a baby, and chuckling to herself. The others had finished piling the stooks and were looking at her curiously. The stooks were heaped in an unstable pyramid in the middle of the field, wanting only the corn-dolly to top it off and to mark the end of the harvest.

‘There. ‘Tis done,’ she said, and tossed it high in the air. She threw it accurately and it balanced on the top of the pile. The reapers moved forward, drawn by the old tradition as if they hardly knew what they were doing, their sickles sharp in their hands.

The game was that they stood some distance from the heap and shied their sickles at it. The sickle that stuck in the dolly belonged to Bill Forrester and he walked wearily towards the stooks to claim his prize and bring it to me. But when it was in his hand he flushed scarlet to the roots of his hair and chucked it, like a football, to the man next to him. They tossed the dolly down the line and then one skilful hand, I don’t know whose, sent it whirling into the air towards me. Tobermory threw up his head in fright and I tightened one hand on the rein and caught the dolly — faster than thought, which would have warned me to let it fall.

It was not one corn-dolly but two. It was two figures coupled. It was the two-backed beast Mama had seen before the fire. A piece of grey ribbon filched from me was round the neck of one of the dollies, and a scrap of linen to indicate Harry was twisted around the other. The head of wheat that had been such a good bawdy joke four seasons ago was now obscene. The phallic sheath of corn was stuck between the other dolly’s straw legs. She was meant to be me; he was meant to be Harry. The secret was out.

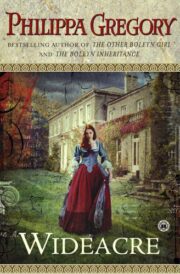

"Wideacre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Wideacre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Wideacre" друзьям в соцсетях.