‘No,’ I said shortly. ‘Perhaps Dr Rose thought you were not well enough to receive letters from home. He forbade visitors, you know.’

‘I guessed there must be some reason I heard from no one,’ said John. It was like swordplay, talking to him. It was like an unending duel. But I was weary.

I gave up. I was almost ready to give up on the rest of my plans too. I was certainly ready to let one evening go without my controlling every move.

‘Excuse me,’ I said to Celia. ‘I am tired. I will go to my room.’

I rose to my feet and the footman sprang to pull back my chair for me. Harry rose and gave me his arm to the west-wing door.

‘It wasn’t Celia in your chair, was it?’ he asked with his usual doltishness. But I was too tired even to fire an opening shot in a battle over a chair, when my husband had looked at me with trained eyes and saw Death in my face.

‘No, it wasn’t the chair,’ I said wearily. ‘She can sit in the damned thing all night if she chooses.’ I turned from him and slipped through the door of the west wing. Lucy undressed me and I dismissed her. Then I took the key from my dressing table and locked the door. I jammed the chair under the handle for good measure. Then I fell into bed and slept as if I wanted never to wake up.

But I had to wake up. There was always work to do, and no one but me who could do it. I had to wake, and dress, and go down to breakfast and sit opposite John, with Celia at the foot of the table, and Harry smiling, at the head, and exchange inanities. Then I had to go to my office and pull out the drawer of bills and spread them out before me and puzzle and worry at them until my head ached. They were a morass of demands to me. I could not see how we had got there; I could not see how to get free. The first simple debts with Mr Llewellyn I had understood well enough. But then the bad weather had come and the sheep had done so badly. Then the cows had some infection and many calves were stillborn. So I had borrowed from the bankers on some of the new wheatfields. But then that had not raised enough, so I had mortgaged some of the marginal lands — the fields on the borders with Havering. But the repayments on those loans were heavy too. I was borrowing and borrowing against the wheat harvest. Praying that the wheat harvest would be such a golden glut that I need never borrow again. That the barns would overflow with wheat in such a surplus that I could sell and sell and sell, and all my debts would vanish — as if they had never been. I spread the bills before me like some complicated patchwork before an inadequate needlewoman, and I sighed with anxiety. I carried this burden alone. I dared not tell Harry how the scheme for the entail had committed us to one debt after another. I mentioned casually that we had obtained credit on the basis of one field or one small farm, but I dared not tell Harry that I was borrowing to repay loans. And then I was borrowing to service loans. And now I was borrowing just to pay wages, to buy seedcorn, to stem the tide of bankruptcy that was lapping at my feet. I dared not tell Harry, and I felt so much alone. The scheme Ralph had planned for Harry: the erosion of his profits and the seeping away of his wealth, I had played on myself. In my one great gamble for total ownership of the land — to have it myself and to see my child in the Squire’s chair — I had gambled everything on the Wideacre harvest. And if that failed: I failed. And if I failed Harry and Celia and John and the children would go down in one resounding crash of debt. We would disappear like all bankrupts did. If we could salvage anything we might buy a little farmhouse in Devon or Cornwall, or perhaps in John’s beastly Scotland. Anywhere where land was cheap and food prices low. And I would never wake to see the hills of Wideacre again. No one would call me ‘Miss Beatrice’ with love in their voice. No one would call Harry ‘Squire’, as if it were his name. We would be newcomers. And no one would know our family went back to Norman times, and that we had farmed and guarded the same land for hundreds of years. We would be nobodies. I shuddered, and pulled the bills towards me again. The ones from Chichester tradesmen I let run. Only the purveyors of the household did I pay regularly. I did not want Celia to learn from the cook or from a housemaid that the merchants were refusing to deliver until their bills were met. So that made a pile of bills that had to be paid at once. Beside them were a smaller pile of creditors’ notes that had to be met this month. Mr Llewellyn, the bank, a London money-lender, and our solicitor, who had advanced a few hundred pounds when I badly needed cash to buy some seedcorn. They had to be paid at once too. With them also was a note from the corn merchant, to whom we owed a few hundred guineas for oats, which we did not grow, for the horses, and a note from the hay merchant. Now we grew fewer meadows I was having to buy in hay, and it was costlier than I had believed possible. It would make sense to reduce the Wideacre stables, which were filled with underworked horses. But I knew that the first Wideacre horse on the market would be seen as a sign that I was selling up, and then the creditors would rush to be first with their notes. They would foreclose on me, in a panic not to be left with a dishonoured note-of-hand, and in their rush for little sums of money, Wideacre would bleed to death from a hundred minor stabs. Each small, irresistible demand added to a total I could not meet. I had no money. I felt the creditors gather around me like a pack of nipping wolves and I knew that I must free myself of them, and free Wideacre of them, but I could not see how. I shuffled the final pile of papers into a heap of debtors who could wait, who would wait. The wine merchants, who knew we had their bill’s worth of wine in the cellars, and who would be circumspect in their demands. The farrier, who had worked on the estate since coming out of his apprenticeship. The carters, who had been paid on the nail for years and years. The cobbler, the gate-mender, the harness-maker — the little men who could beg that their bills be paid but who could do nothing against me. It was a large heap of bills, but they were all for small sums. My failure to pay might ruin the little tradesmen, but they could not ruin me. They could wait. They would have to wait. It made three tidy piles. It got me no further forward. I folded them up and stuffed them back into the drawer. I did not have to see them to remember that I was drowning in debt. I remembered it every waking moment, and my nights were full of dreams of strange men with town accents saying to me, ‘Sign here. Sign here,’ in a long dream of horror and fear of the loss of Wideacre. I slammed the desk drawer shut with sudden impatience. There was no one to help me, and I was alone with this burden. All I could hope for was the old magic winds of Wideacre blowing my way again and a warm wind blowing out of a hot harvest sun to make the land golden, and set me free. I rang the bell and ordered that Richard be dressed for a drive and brought to me in the stable yard. I could not stay indoors. The land no longer loved me, I could not take Richard at a whirling trot down the drive and show him the trees with the confidence of my papa on the land he owned outright, but I could still go out. It was still my land. I might still escape the intractable, unanswerable sheets of bills by driving out under a clear blue sky with my son. He came to me beaming, as he always did. Of all the children I have ever seen Richard was the most sweet-tempered. One of the naughtiest too, I admit. At the age when Julia used to hold her toes in her warm cradle and coo to the delight of her grandmama and Celia, Richard was heaving himself up with chubby arms, and trying to climb out. Julia would play with a moppet in her cot for hours, but Richard would hurl it out on to the floor and then bawl for it to be returned to him. If you were fool enough to go to him he would play the same trick again. And again. Only a paid servant would return the number of times Richard thought necessary, before his dark eyelashes would close on that smooth and perfect cheek. He was the bonniest baby. The naughtiest, the sweetest, child. And he adored me. So I caught him from his nurse’s arms and hugged him hard and smiled when I heard his crow of delight at my sudden appearance. I passed him up to her when she was settled in the gig and made sure she held him tight. Then I put his rattle in his grabbing little hands and swung up beside them. Sorrel trotted down the drive and Richard waved the rattle at the flying trees and at the flickering shadows and sunlight. On either side of the silver toy were little silver bells and they tinkled like sleighbells and made Sorrel throw up his head and step out faster. I drove at a spanking pace down the drive and then up to the London road. We were in time to see the mailcoach go by in a whirl of dust and Richard waved to the passengers on the roof and a man waved back. Then I turned the gig and we headed for home. A small enough outing, but when you love a child your world shrinks to a proper size of little delights and little islands of peace. Richard brought me that. If I loved him for nothing else, I would have loved him for that. We were nearing the turn of the drive when he choked. A funny sound, unlike his usual open-mouthed barks of coughs. He gave an open-mouthed retching, a sort of gasping for air, a sound unlike anything I had ever heard before. I hauled on the reins and Sorrel skidded to a halt. My eyes met those of his nurse in mutual bewilderment and then she snatched the rattle from his hands. One of the tiny tinkly silver bells on the end was missing. He had swallowed it and he was gasping, reaching for his life’s breath around it.

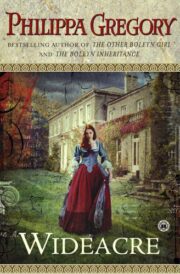

"Wideacre" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Wideacre". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Wideacre" друзьям в соцсетях.