Klim heard the sound of heavy boots on the stairs.

“There’s a safe in the bedroom on the second floor, sir,” cried Sergeant Trots.

Johnny had the pharmacist by his lapels.

“Ask him where the keys are,” he told the translator.

The pharmacist started to babble something, spraying the policemen with his saliva in his terror. Johnny pushed him away in disgust.

“What is he saying?”

The translator pulled a sour face. “He doesn’t understand a thing, sir. It seems he’s from a different province and doesn’t speak Shanghainese.”

“The bastard’s lying.”

Johnny pulled a revolver out of a holster and shot the wall behind the pharmacist’s back. The man gave a whimper and fell on the floor face down.

“Feeble people,” said Felix through his teeth.

Johnny searched the pharmacist’s desk. “Here are the keys. Let’s go.”

They went up the stairs. In the bedroom, a woman with two terrified children sat in the far corner of a big bed with a red cover on it.

“Clear them out,” ordered Johnny, and the policemen quickly took them out of the room.

Behind the bed was a huge iron safe covered with an embroidered spread. A bronze candlestick and vases were placed on top of it. Johnny removed the spread and, after fiddling with the keys for a few seconds, finally had the safe open.

Klim craned his neck to see what was inside.

“Wow!” he whistled looking at the parcels piled up one on top of the other.

Felix pulled out a pen knife and cut several of the parcels open.

“It’s Indian opium,” he said after trying the dark sticky paste. “And here’s some cocaine.”

Johnny took a thick binder out of safe and called the translator over. “What are these papers?”

The Chinese glanced through it. “These are lists of suppliers, sir.”

Johnny’s eyes lit up. “Well, this should see our friendly neighborhood pharmacist in prison for a while.”

There was stamping on the stairs, and a boy of about fourteen burst into the room. He was hiding something under his green shirt.

“Grab him!” screamed someone from downstairs.

Sergeant Trots grabbed the youngster by his shoulder, but the boy took a revolver from inside his shirt and fired at him.

The sergeant, bleeding heavily, fell down the stairs. The youngster headed to the window and, crashing into Klim on the way, pointed his revolver at him.

This is it, Klim thought.

The revolver went off again, the boy yelped, and something heavy hit the floor.

A moment later Klim realized what had happened: Felix had hurled the heavy candlestick at the boy, breaking his wrist.

More police arrived on the scene followed closely by reporters and photographers. All of them wanted the full story from Felix, but he was too modest and left his boss to do the explaining.

“Felix Rodionov is that rare breed of man whose actions speak louder than his words,” Johnny said proudly. “He came to our station hoping to get a job, but he was so emaciated that the commissioner was about to turn him down. However, I asked him, ‘What can you do?’ And he told me to try to attack him with a knife. What do you think happened? The son of a gun knocked the knife right out of my hand! If I’ve told you once, gentlemen, I’ve told you a thousand times: We shall continue to man our forces on the basis of race. The Russians are an asset to the force that the Chinese can never be.”

Johnny then saddled up his hobby horse and began to hold forth on the perfidious Chinese and their numerous conspiracies against the ruling whites.

“More than two-thirds of our men are Chinese and Sikhs from India,” he said warming to his theme. “The same could be said of the French Concession, but they have Vietnamese instead of Sikhs.”

The reporters recorded his every word, and Klim who had heard his sermon many times before, went off to talk to Felix.

He found the young man sitting on a bench on the back porch, smoking and stroking a fat ginger cat at his feet.

“Thank you for saving my life,” Klim said as he sat down next to him.

Felix sniffed. “My pleasure.”

They got to talking. Felix had been an orphan from Omsk and had joined the cadets at a very young age. He and his fellow trainee officers had been among the first to be evacuated to Vladivostok and then to China after the outbreak of the civil war.

A Shanghai merchant had allowed the boys to stay in his house, and there they had lived in close quarters. Space had been so scarce that they had to take turns to sleep. It was hard to feed seven hundred teenagers, and the French Consul resolved to hold a lottery for the younger orphans, and that was how they raised funds. The majority of the boys dug graves and guarded warehouses for a living, and only a few, like Felix, had been lucky enough to find decent jobs.

“I really hope I’ll get promoted to inspector one day,” he said dreamily. “Inspectors get three hundred dollars a month and a paid vacation of seventeen days a year or, if you want, seven months every five years. But first I will need to distinguish myself.”

“Do you have any ideas how you’re going to do this?” Klim asked.

Felix nodded. “My friend works as a doorman at the Three Pleasures pub. He says that all the alcohol they sell there is bought duty-free and delivered by the local Czechoslovak Consul. I’ve suggested having him arrested a long time ago, but Johnny is reluctant to go there because it’s a French protectorate. But the consul, Jiří Labuda, is a resident in the International Settlement, and therefore he comes under our jurisdiction.”

“Who did you say?” Klim asked, stunned. “Jiří Labuda?”

“That’s his name,” Felix nodded. “If you want, we could track him down together. You’ll get an exclusive for your paper, and I’ll get my promotion. It’s a great story—a respectable diplomat turned small-time crook.”

Klim didn’t know what to think. What kind of people had Nina got herself mixed up with?

“There won’t be the slightest problem,” Felix persuaded. “This Labuda is a sickly individual. One punch and he’ll be done for. His driver won’t be so easy. He’s as big as an ox. But between the two of us, we’ll be more than a match for them.”

“Let’s go hunting then,” said Klim after a pause.

Felix beamed. “Good. I’ll see you at the Three Pleasures tomorrow at seven o’clock.”

11. THE HOUSE ARREST

As her pregnancy progressed, Nina stopped giving her parties.

Jiří was furious. “How are we going to pay our bills now?” he yelled at her. “You’re no more a mother than I’m Napoleon. Have an abortion before it’s too late.”

Nina could have killed him on the spot.

“Don’t ever talk to me about my baby again!” she whispered in such a cold fury that Jiří quickly retreated to the next room.

Don Fernando was also disappointed that Nina was bowing out of the liquor business and kept badgering her with new ideas for making money out of the Czechoslovak Consulate.

“I’ve got a brilliant idea,” he said to Nina. “Why don’t we ship liquor as a diplomatic cargo? They have brought in Prohibition in America, and the prices have gone through the roof. We can brew our own ‘French wine’ right here, in China, and smuggle it into the United States through Canada.”

Nina soon fell out with the Don as well. She felt that something amazing was happening to her, as if some immense tectonic shift was going on inside her body, and the idea of spending her time and energy on liquor seemed sacrilegious to Nina.

Her perception of the world was changing fundamentally. Street smells, such as car fumes, tobacco, and fried food, were all sickening to her, and the sight of homeless mothers with children would make her shudder with horror. Nina was incapable of thinking about anything except her baby. Her greatest pleasure was to visit the toy store or a workshop where they made adorable playthings for infants. The thought that caused her the most turmoil was the question of her child’s citizenship. When the baby arrived, she would need to make sure that its documents were in order. But how was she going to do this? Would she really have to buy fakes? She was determined that there should be nothing false in her child’s life.

The past and future took on a new meaning. Until recently, her fight with Daniel had seemed a complete disaster, but now she was glad they had broken up. It would be quite something, she thought, if he were to divorce Edna and then find out about my pregnancy.

Nina tried to shut Klim out of her mind. If she were to find him and tell him about their child, he was bound to assume that she was just trying to land him with someone else’s baby. With all the scandal that had followed her friendship with Daniel, Klim was sure to assume they had actually had an affair.

Nina wanted her baby to be important not only for herself but for other people too, and she couldn’t resist the urge to talk about it, if only to the servants. But they gave her such outlandish advice that she was left at a complete loss. According to them, an expectant young mother should never leave the house, wash her hair, or sew, and as for standing in the wind, well, that was totally out of the question.

Nina at least found some consolation with Tamara, who—thank God—had lost her interest in the parties and was happy to spend hours discussing matters relating to motherhood.

“I’m sure,” Nina said, “everybody is critical of me for having a baby by an unknown father. There isn’t a decent woman who will let me into her house anymore. Except for you, of course.”

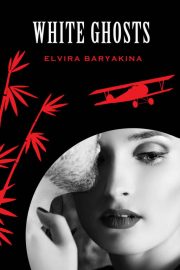

"White Ghosts" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "White Ghosts". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "White Ghosts" друзьям в соцсетях.