“There is that,” Arrow said hopefully.

“So before you go feeling sorry for yourselves,” Wray said with a grimace, “remember, I’d give anything to be in your position.”

He was right, of course. And if Harry were truthful with himself, he must admit that beneath the resentment he felt about being pulled into Prinny’s scheme, there was a spark of hope…

That he would win the wager. And be able to walk into any ballroom in London and not have to worry about someone trying to marry him off.

He patted Wray’s shoulder. “You’re a good man.”

It was his way of saying farewell to a noble bachelor, and everyone there knew it.

Wray tried to buck up and grin, but it turned into another wince. He got up and stumbled toward the door. “I’ve got to go, gentlemen. I—I’ll see you”—he hesitated—“after I’m married. At church. Or a musicale. Or something equally boring.”

And he shut the door behind him.

There was a grave silence, but Harry turned to the others. “I’d like to raise a toast,” he said.

Arrow, Lumley, and Maxwell each wore almost identical somber looks, but they lifted their glasses anyway.

“To the Impossible Bachelors,” Harry said with spirit. “And this impossible wager. May we survive it handily, with our freedom intact.”

“Here, here,” the others said in chorus.

Everyone drained their glasses.

“One more thing,” Harry said with a grin. “I propose the damned bookcase is nailed shut before we leave tonight. All in?”

“All in!” they cried.

Just as he knew they would.

Chapter 2

Thanks to the Providence School for Wayward Girls, which took her in hand at age thirteen, twenty-one-year-old Molly Fairbanks was no longer a silly romantic—she was a silly romantic with superb posture. She sat perfectly straight in her chair at the rather seedy inn where she and Cedric Alliston were taking a bit of nuncheon before eloping to Gretna Green.

Not that she could actually eat. She was much too excited. And confused. The way she suspected a bird let out of a cage is confused moments before it flies away to freedom.

To honor her emancipation, she’d forgone her usual dreary traveling dress. She’d worn instead her favorite white muslin gown paired with her late mother’s gloves and a navy blue and white striped silk parasol Penelope had just sent her from Italy, where she and her family were on a six-month painting holiday.

“Cedric—” Molly toyed with her glass of ratafia. “If Papa weren’t so damnably rich—and far away at the moment—would you still be running off with me?”

“What a sh-illy question,” Cedric said, working his jaw in a grand manner as he cut his sausage. He often spoke as if he were clenching a knife between his back teeth, which should have seemed terribly Londonish to a girl who’d been rusticating in Kent an age with an addled crone of a cousin, and before that, a cold, stone school high atop the wind-scoured Yorkshire dales.

But as Molly had never been to London, she couldn’t be impressed.

“The elopement izzh what it izzh,” Cedric said, glancing at the gold watch he wore on his emerald green waistcoat. “And we are what we are.”

Molly blinked. “I don’t understand you.”

Which was nothing new. Cedric was like a puzzle. And she was like a person who, um, didn’t like puzzles. Particularly the kinds with one piece missing. Cedric seemed one of those.

He sighed, his perfectly chiseled jaw framed by the exceedingly high points of his shirt collar. “Our nature is sh-tamped upon us, Mary. Every piece of broken pottery your father and I pull from the earth reveals the human condition. And we can’t esh-cape it.”

“Oh,” she said politely. How did every conversation they had come round to broken pottery?

Cedric pointed his fork at her. “Unlike your perfectly proper sister Penelope, you are nothing more, or lesh, than a well-bred young lady—of too high spirits, I might add—who requires constant direction from a better mind. And I…I am the brilliant treasure hunter—of noble visage,” he added with a loft to his brow, “who shall provide that tutelage. It’s our lot in life.”

He shrugged and popped a piece of sausage in his mouth.

Oh, pish posh. Molly pursed her lips. Cedric was no treasure hunter. He was an impoverished social climber—Cousin Augusta’s husband’s nephew—who served as an assistant to her father. And Penelope wasn’t perfectly proper, either. Any girl who kissed her fiancé’s brother couldn’t qualify as perfectly proper, could she? And Molly loved her long-married sister all the more for it.

Molly knew ladies weren’t supposed to seethe, but really, why was it that only gentlemen were allowed to speak boldly? And why were they permitted to boast about themselves—even contradict themselves!—while ladies must remain meek and…and boring?

“Someday,” she said, leaning toward Cedric, “someday you shall call me Molly. And you’ll never go back to calling me…Mary.”

“I beg to differ.” He slurped at his wine.

“I beg to differ.”

“You can’t. I already did.” He set his goblet down with a thunk.

“We both can. You don’t have a license to differ alone.”

Cedric scoffed. “You make no sen-sh.”

“I beg to differ,” she said.

Although secretly, in her deepest heart, she realized Cedric had a point. She must have lost her mind to have agreed to stay at home, pour out Cousin Augusta’s tea, and listen to her complain of a brass band playing in her ears—while Papa traipsed about Europe hunting treasure with Cedric for the past three years.

And when Papa did return to visit Marble Hill, Molly spent each night at the dining room table (sitting quite straight) while Cedric and her father prosed on about chunks of broken, thousand-year-old vases for hours.

Molly didn’t like dirt. Or dark, broken things pulled out of the ground.

She liked flowers. Romantic novels. Fresh air. And dancing.

And although Cedric did look rather like Apollo, with his shining halo of golden curls, patrician nose, and long, golden lashes framing cerulean blue eyes, she didn’t love him. He was too much of a boor and a bore—and sometimes even a boar, the way he snuffled and snorted when he ate—to love.

Of course, part of her—the silly romantic part which had read Pride and Prejudice thirteen times—thought it would be awfully nice if he loved her. Because maybe then she’d come to love him back. Someday. After her senses had been dulled by age or…or perhaps after he’d done something heroic.

She watched him shake out his lacy cuffs and lean back in his chair, chewing with his nose in the air.

Very well. He’d never do something heroic. But she had no other options. Clearly. Other than spinsterhood. Or being driven mad by Cousin Augusta’s imaginary brass band.

At least, being married to Cedric, Molly could finally see London and Paris and kick up her heels while Cedric and Papa were away.

But her daydream of a future as a social butterfly was interrupted when a man and a woman swept into the taproom, drawing not just her attention but everyone’s. The woman was extremely beautiful, if a trifle overdone, in a tulip pink gown with a neckline that showed her décolletage to great advantage.

“She’s lovely in a tartish way, is she not?” whispered Molly to Cedric.

The vision in pink lowered her brows, flicked her curls back, and stuck her hand on her hip. But her male companion at the bar either didn’t notice her or was ignoring her. He wore a simple lawn riding shirt and buff breeches tucked in tall black boots, one of which rested jauntily on a brass rail near the floor. Molly couldn’t help but observe the impressive breadth of his shoulders and the glossy blackness of the hair spilling over his collar.

Cedric placed his fork and knife on his plate and gazed at the woman in pink. “She is Aphrodite,” he said simply. “Come to life.”

Molly watched as Aphrodite compressed her lips, wended her way through the tables without her consort, and approached a table adjacent to theirs. Looking over her shoulder, the beauty saw Cedric and smiled slowly, like a dewy rose blooming at the kiss of the sun.

Cedric drew in a breath.

Molly wondered if Cedric ever thought she was fine-looking. She doubted it. No matter how often she pulled on her nose in front of her looking glass at home, it stayed short and snub, not aristocratic and elegant. Her mouth, she knew, was wider than the river Thames. Her eyes were a Wedgwood blue, but Miss Dunlap, the headmistress at Providence School, said they were too impertinent to be ladylike, and Molly’s hair…well, it was her greatest annoyance. It was the color of molasses and as thick as it, too, always slipping out of its pins.

“Hello,” said Molly, and gave the woman a little wave.

Aphrodite inclined her head in cool acknowledgment of Molly’s greeting, but her expression grew much…warmer when she looked at Cedric. There was silence between them, but Molly sensed an invisible golden thread extending from Cedric to the woman. And that thread thrummed with tension. It was the call of one beauty to another, the recognition that one perfect specimen of physical form had found its ideal mate.

But that was a silly thought, Molly said to herself. She was here with Cedric and they were going to Gretna together.

He pushed his chair back, stood up, and strode to the woman’s table. “Please allow me to assist you,” he said to her, and pulled out a chair.

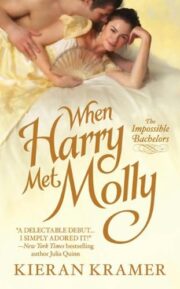

"When Harry Met Molly" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "When Harry Met Molly". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "When Harry Met Molly" друзьям в соцсетях.