“Still spending time with this boy?” he asks. The tone is embarrassingly obvious.

I flick a few needles from his shoulder. “The boy’s name is Caleb,” I say, “and he doesn’t work here, so you can’t scare him out of talking to me. Plus, you have to admit, he is our best customer.”

“Sierra…” He doesn’t finish, but I want him to know that I’m not blind to our circumstance.

“We’re only here a few more weeks. I know. You don’t need to say it.”

“I just don’t want you getting your hopes up,” he says. “Or his, for that matter. Remember, we don’t even know if we’re coming back next year.”

I swallow past the lump in my throat. “Maybe it doesn’t make sense,” I say. “And I’m fully aware that I’m not usually like this, but… I like him.”

The way he winces, anyone watching would think I told him I was pregnant. Dad shakes his head. “Sierra, be—”

“Careful? Is that the cliché you’re looking for?”

He looks away. The unspoken irony is that he and Mom met this exact way. On this lot.

I brush another needle from his hair and kiss him on the cheek. “I hope you think I usually am.”

Caleb approaches the counter and sets down a tag from his next tree. “Tonight’s family is getting a beauty,” he says. “I noticed it the last time I was here.”

Dad smiles at him and politely claps him on the shoulder and then walks away without muttering a word.

“That means you’re winning him over,” I explain. I grab a sleigh-shaped cookie tin from below the register and Caleb raises his eyebrows. “Stop salivating. These are staying wherever we take the tree.”

“Wait, you made those for them?” I swear, it’s like his smile lights up the entire Bigtop.

After we deliver the tree and cookies to tonight’s family, Caleb asks if I would like to taste the best pancake in town. I agree, and he drives us to a twenty-four-hour diner that was probably last remodeled in the mid-1970s. A long stretch of windows lit by orange-hued lights frame a dozen booths. There are only two people seated inside, at opposite ends of the diner.

“Do we need to get tetanus shots to eat here?” I ask.

“This is the only place in town you can get a pancake as big as your head,” he says. “And do not tell me that hasn’t been a dream of yours.”

Inside the diner, a handwritten sign duct-taped to the register says Please seat yourself. I follow Caleb to a window booth, walking beneath red Christmas ornaments hung by fishing line to the ceiling tiles. We slide into a booth whose green vinyl covering has seen better days, but more than likely not in this century. After we each order the “world famous” pancake I fold my hands on the table and look at him. He thumbs the top of a large syrup pourer beside the napkins, sliding the lid open and shut.

“There’s no marching band,” I prompt. “If we talk, I should be able to hear you just fine.”

He stops playing with the syrup and leans back against the booth. “You really want to hear this?”

I honestly don’t know. He knows I’ve heard the rumors. Maybe I haven’t heard the truth. If the truth is better, he should jump at the chance to tell me.

He picks at the cuticle on his thumb.

“You can start by explaining why you haven’t used your new comb,” I say. The joke falls flat, but I hope he knows I’m trying.

“I used it this morning,” he says. He scrubs his fingers through his hair. “Maybe the one you got was defective.”

“I doubt it,” I say.

He takes a sip of water. After several more moments of silence, he asks, “Can we start by you telling me what you’ve heard?”

I bite my lower lip, considering how to say this. “Exact words?” I say. “Well, I heard you attacked your sister with a knife.”

He closes his eyes. His body, almost undetectably, rocks back and forth. “What else?”

“That she doesn’t live here anymore.” It feels wrong that I even notice the butter knife on the napkin beside his hands.

“She lives in Nevada,” he says, “with our dad. She’s a freshman this year.”

He looks toward the kitchen, maybe hoping the waitress will interrupt our conversation. Or maybe he wants to get through it without interruption.

“And you live with your mom,” I say.

“Yes,” he says. “Obviously that’s not how things started.”

The waitress sets down two empty mugs and then fills them both with coffee. We each grab creamers and packets of sugar.

He’s still stirring his drink when he continues. “When my parents split, my mom took it really hard. She lost so much weight and cried a lot, which is normal, I guess. Abby and I both stayed with her while they figured things out.”

He takes a sip of his drink. I pick up mine and blow away the steam.

“Abby and I were given our own lawyer, which happens in some cases.” He takes another sip and then holds his mug in both hands, staring into it. “That’s when it all started. I was the one who said we should stay with our mom. I convinced Abby it’s what we needed to do. I told her she needed us and that Dad would be fine.”

I take a sip of my coffee while he still stares into his.

“But he wasn’t fine,” Caleb says. “I think I knew that for a while but I kept hoping he would pull it together. I think if I actually saw him every day, looking as hurt and broken down as my mom, I might have chosen him.”

“Why do you think he wasn’t fine?” I ask.

The waitress sets down our plates. The pancakes really are the size of our heads, but it does nothing to bring about the easy conversation Caleb probably hoped for when he chose this place. Still, they offer a distraction for both of us as the talk continues. I pour syrup over mine and, with a butter knife and fork, start cutting up half of it.

“Before they split, our whole family used to go nuts this time of year,” he says. “We went hardcore, from decorating to all these things we did with our church. Sometimes even Pastor Tom would go caroling with us. But when Dad moved to Nevada, I found out everything did stop for him. His house was this dark and depressing place to visit. Not only were there no Christmas lights, half the regular lights in his house were burned out. He didn’t even unpack most of his boxes after being there for months.”

He takes a couple of bites of his pancake, looking down at his plate the whole time. I consider telling him he doesn’t need to tell me more. Whatever happened, I like the Caleb sitting in front of me now.

“After our first visit to his place, Abby bugged me about him all the time. She was so mad at me for how he was dealing with things, for making us choose Mom. And she wouldn’t let up about it. She’d say, ‘Look what you did to him.’”

I want to tell Caleb his dad isn’t his responsibility, but he must know that. I’m sure his mom told him that a thousand times. At least, I hope she has. “How old were you?” I ask.

“I was in eighth grade. Abby was in sixth.”

“I can remember sixth grade,” I say. “She was probably trying to figure how everything fit together in this new life you all had.”

“But she blamed me for how they weren’t fitting together. And I blamed me, because some of it was true. But I was in eighth grade. How could I know what was best for everyone?”

“Maybe there was no best,” I say.

For the first time in minutes, Caleb looks up. He attempts a smile, and while it barely registers, I think he now believes that I do want to understand.

He takes a sip of his coffee, leaning forward more than lifting his hands. This is the most fragile I’ve seen him. “Jeremiah had been my friend for years—my best friend—and he knew how much Abby was on me about this. He called her the Wicked Witch of the West.”

“That’s a good friend,” I say. I cut up more of my pancake.

“He’d say it in front of her, too, which of course made her even madder.” He laughs a little, but when he stops, he looks out the window. His reflection against the dark glass feels cold. “One day, I snapped. I couldn’t take the accusations anymore. I just snapped.”

With my fork, I lift a piece of pancake dripping with syrup, but I don’t bring it to my mouth. “What does that mean?”

He looks at me. His entire body echoes hurt and grief more than any remaining anger. “I couldn’t listen to it anymore. I don’t know how else to describe it. One day she screamed at me, the same thing she always screamed: that I’d ruined our dad’s life, and hers, and Mom’s. And some switch in me… flipped.” His voice quivers. “I ran to the kitchen and grabbed a knife.”

My fork remains frozen over my plate, my eyes locked with his.

“When she heard this, she ran to her room so fast,” he says. “And I ran after her.”

He holds on to his mug with one hand. With his other hand, he numbly folds his napkin until it conceals the butter knife. I can’t tell if he’s aware he did this. If he is, I don’t know if it was for my sake or his.

“She got to her room and slammed the door and…” He leans back, closes his eyes, and puts his hands in his lap. The napkin rolls open. “I stabbed her door with the knife over and over. I didn’t want to hurt her. I would never hurt her. But I could not stop stabbing the door. I heard her screaming and crying to our mom on the phone. Finally, I dropped the knife and just slumped onto the floor.”

It comes out as a whisper, or it could be all in my head: “Oh my God.”

He looks up at me. His eyes beg for understanding now.

“So you did it,” I say.

“Sierra, I swear to you, I’ve never had anything like that happen to me before or since. And I promise, I would never have hurt her. I didn’t even check if she locked the door, because that wasn’t what it was about. I think I just needed to show how much everything was hurting me, too. I’ve never physically hurt anyone in my life.”

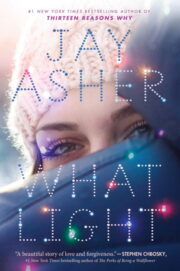

"What Light" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "What Light". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "What Light" друзьям в соцсетях.