“You, Caleb, are a man of multitudes,” I say.

Without taking his eyes off the drawing, he says, “I need to point out that you used multitude in a sentence.”

“It’s not the first time,” Heather says.

Caleb looks at her. “She may be the first person in this diner to ever use it.”

“You—both of you—are ridiculous,” I say. “Heather, tell him you’ve used peruse in a sentence before. It’s two syllables.”

“Of course I…” She stops herself and looks at Caleb. “No, actually, I probably never have.”

Caleb and Heather bump fists.

I reach over and snatch that silly looking soda jerk hat from Caleb’s head. “Then you should use more interesting words, sir. And buy yourself a comb.”

He holds out his hand. “My hat, please? Or the next time I buy a tree, I’m paying for it all in one-dollar bills, each one turned a different direction.”

“Fine,” I say, still holding his hat out of reach.

Caleb stands up, his hand out for his hat, and I eventually give it back. He perches the completely uncool thing back on his head.

“If you do come for a tree, don’t expect any drawings,” I say, “but I work from noon to eight today.”

Heather stares at me, a half-smile appearing on her face. When Caleb leaves to check on the other customers, she says, “You basically just asked him to stop by.”

“I know,” I say, lifting my mug. “That was me obviously flirting.”

I get to work an hour before Mom thought I would be needed, which is a good thing. The lot is busy and a flatbed truck full of replenishing trees from the farm arrived early. With my work gloves on I climb up the ladder at the back of the truck. I step carefully onto the top layer of trees, all netted and laid sideways one on top of the other, their wet needles brushing against the bottom of my pants. It must have rained for a good part of the trip, giving the trees a smell that’s close to home.

Two more workers join me up here, moving their feet as little as possible to keep the branches from snapping. I lace my fingers into the netting of a tree, bend my knees, and slide it over the edge of the truck so another worker can grab it and carry it to a growing stack behind the Bigtop.

Andrew takes the next tree I lower and, rather than carry it to the Bigtop himself, he passes it off to someone else.

“We got this!” he shouts up to me, clapping his hands twice.

I almost tell him we aren’t in a race, but Dad drops his hand on Andrew’s shoulder.

“The outhouses need restocking, pronto,” he says. “And let me know if you think they need a deeper cleaning. That decision’s up to you.”

When my muscles start to tire, I take a moment to stretch my back and catch my breath. Even when exhausted, it’s easy to keep a smile going on the lot. I look out at the customers moving through our trees, the joy on their faces evident even from way up here.

I’ve been surrounded by these sights my entire life. Now, I realize that the only people I’m seeing are the ones who will have a tree for Christmas. The people I don’t see are the families who can’t afford a tree even if they want one. Those are the people Caleb brings our trees to.

I put my hands on my hips and twist in both directions. Beyond our lot—beyond the last house in the city—Cardinals Peak rises into the cloudless pale blue sky. Near the top of that hill are my trees, indistinguishable from here.

Dad climbs the ladder to help me slide more trees down to the workers. After lowering a few, he looks at me with his hands on his knees. “Did I react too strongly with Andrew?” he asks.

“Don’t worry,” I say, “he knows I’m not interested.”

Dad lowers another tree, a delighted smile on his face.

I look out over the workers on the lot. “I think everyone here knows I’m off-limits.”

He stands up and wipes his wet hands on his jeans. “Honey, I don’t think we put too many restrictions on you. Do you?”

“Not at home.” I send down another tree. “But here? I don’t think you’d be too comfortable with me seeing anyone.”

He grips another tree, but then stops to look at me and doesn’t pass it over the side. “It’s because I know how easy it can be to fall for someone in a very short time. Trust me, leaving like that is not easy.”

I lower two more trees and then notice he’s still looking at me. “Okay,” I say. “I understand.”

With the trees finally unloaded, Dad takes off his gloves and shoves them into his back pocket. He heads to the trailer for a short nap and I walk toward the Bigtop to help ring up customers. I pull back my hair to wrap it into a bun when I see, standing at the counter, Caleb in his street clothes.

I let my hair fall to my shoulders and scrape a few strands forward.

I pass him by as I head to the counter. “Back again, making someone else’s Christmas bright?”

He smiles. “It’s what I do.”

I nod for him to follow me to the drink station. Next to my Easter mug I set a paper cup for him and then I tear open a packet of hot chocolate. “So tell me, what made you start doing this with the trees?”

“It’s a long story,” he says, and his smile falters a bit. “If you’ll take the simple version, Christmas was always a big deal in my family.”

I know his sister doesn’t live with him anymore; maybe that’s part of the non-short story. I hand him his cup of hot chocolate with a candy cane stirrer. His dimple reappears when he sees my Easter mug, and we both take a sip while looking at each other.

“My parents would let my sister and me buy whichever tree we wanted,” he says. “They’d invite friends over and we’d all decorate the house. We’d cook a pot of chili and afterwards we’d all go caroling. Sounds really cheesy, right?”

I point to the flocked trees around us. “My family survives on cheesy Christmas traditions. But that doesn’t explain why you buy them for other people.”

He takes another sip. “My church does this big ‘necessity drive’ during the holidays,” he says. “We collect things like coats and toothbrushes for families that need them. It’s great. But sometimes it’s nice to give people what they want instead of only the necessities.”

“I can appreciate that,” I say.

He blows steam from the surface of his drink. “My family doesn’t do the holidays like we used to. We put up a tree, but that’s about it.”

I want to ask why, but I’m sure that’s also part of the non-simple version.

“Long story short, I took the job at Breakfast Express and realized I could spend my tips on families who wanted a Christmas tree but couldn’t afford it.” He stirs the peppermint stick. “I guess if I earned more tips, you’d see even more of me.”

I sip up a small marshmallow and lick it from my lip. “Maybe you should put out a separate tip jar,” I say. “Draw a little tree on it and have a note saying what the money’s for.”

“I thought about that,” he says. “But I like using my money. I’d feel bad if that extra tip somehow took away from a charity that gives people what they actually need.”

I set my mug on the counter and point at his hair. “Speaking of things people need, don’t move.” I run behind the counter for a small paper bag. I hold it out to Caleb and his eyebrows raise.

He takes the bag, looks inside, and laughs so hard when he pulls out the purple comb I picked up for him at the pharmacy.

“It’s time to start tackling those flaws,” I say.

He slides the comb into his back pocket and thanks me. Before I can explain that the comb is first supposed to go through his hair, the Richardson family walks into the Bigtop.

“I was wondering when you’d show up!” I give both Mr. and Mrs. Richardson hugs. “Aren’t you normally day-after-Thanksgiving tree buyers?”

The Richardsons are a family of eight who have been buying their trees from us since they only had two children. Every year they bring us a tin of home-baked cookies and chat with me while their kids bicker over which tree is the most perfect. Today, their kids all say hi to me and then run out to start looking.

“There was car trouble on the way to New Mexico,” Mr. Richardson says. “We spent Thanksgiving in a motel room waiting for a fan belt to arrive.”

“Thank you, God, they had a pool there or the kids would have killed each other.” Mrs. Richardson hands me this year’s blue snowflake-covered cookie tin. “We tried a new recipe this year. We found it online and everyone swears it’s delicious.”

I pull off the lid and pick out a slightly misshapen snowman cookie that has a ton of frosting and sprinkles. Caleb’s leaning in, so I offer him the tin and he takes a mutated reindeer with buck teeth.

“The younger kids helped out this year,” Mr. Richardson says, “which you could probably tell.”

I moan around the first bite. “Oh my, yum… These are delicious!”

“Enjoy them now,” Mrs. Richardson says, “because next year I’m going back to the Pillsbury version.”

Caleb catches a crumb falling from his lips. “These are amazing.”

“A lady at work says we should try some peppermint bark,” Mr. Richardson says. “She says even the kids can’t mess it up.” He tries to reach into my tin for a cookie, but Mrs. Richardson grabs his elbow and pulls him back.

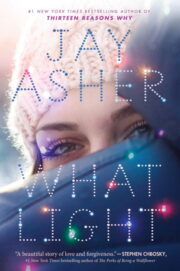

"What Light" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "What Light". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "What Light" друзьям в соцсетях.