I laugh and return to my station behind the counter. “He’s cute. That’s all. It’s not enough for me to get involved.”

“Well, that’s very wise,” Heather says, “but he is the only guy I’ve seen you this awkward around since I’ve known you.”

“He was awkward, too!”

“He had his moments,” she says, “but you won that contest.”

After a phone call where I describe my week in French to Monsieur Cappeau, Mom lets me leave work early. Heather holds a movie marathon every year starring her latest celebrity crush and a bottomless bowl of popcorn. Dad offers me his truck, but I decide to walk. Back home I would have grabbed his keys in a second to avoid the cold. Here, even in late November, it’s relatively nice out.

The walk takes me past the only other family-owned tree lot in town. Their assortment of trees and the red-and-white sales tent take up three rows of a supermarket parking lot. I always stop by a couple of times during the season to say hi. Like my parents, the Hoppers rarely leave their spot once the selling begins.

With his arms buried into the top half of a tree, Mr. Hopper leads a customer into the parking lot. I walk toward them, squeezing between parked cars, to say hello for the first time this year. The guy carrying the trunk of the tree drops his end onto the lowered tailgate of a purple truck.

Caleb?

Mr. Hopper pushes the tree the rest of the way in. He turns in my direction and I don’t spin away fast enough. “Sierra?”

I exhale deeply and then turn back around. Wearing a checkered orange-and-black jacket and matching earflapped hat, Mr. Hopper walks over and embraces me in a warm hug. I use that squeeze to look over at Caleb. He leans his back against the truck and his eyes smile at me.

Mr. Hopper and I catch up quickly and I agree to stop by some more before Christmas. When he heads back to his lot, Caleb is still looking at me, sipping something from a paper cup with a lid.

“Tell me what your addiction is,” I say. “Is it the Christmas trees or the hot drinks?”

His dimple digs in deep and I walk closer. His hair sticks up in front, like all this tree lifting doesn’t allow him enough time to brush it. Before he answers my question, Mr. Hopper and one of the workers drop a second tree into Caleb’s truck.

Caleb looks at me and shrugs.

“Seriously, what is going on?” I ask.

He nonchalantly lifts the tailgate shut as if finding him at another tree lot isn’t extremely odd. “I’d like to know what brings you here?” he asks. “Are you checking out the competition?”

“Oh, there’s no competition at Christmastime,” I say. “But since you do appear to be an expert, who’s got the best lot?”

He takes a sip of his drink and I watch his Adam’s apple bob as he swallows it down. “Your family has them beat,” he says. “These guys were all out of candy canes.”

I feign disgust. “How dare they.”

“I know!” he says. “Maybe I should stick with you guys.”

He takes another sip, followed by silence. Is he implying there will be even more trees? That means more opportunities to run into him, and I don’t know how I should feel about that.

“What kind of person buys this many trees in a day?” I ask. “Or even in a season?”

“To answer your first question,” he says, “I’m addicted to the hot chocolate. I suppose if I have to have an addiction, it’s not the worst one. To your second question, when you own a truck, you end up with plenty of ways to fill it. For example, I helped three people my mom works with move over the summer.”

“I see. So you’re that guy,” I say. I walk up to one of his trees and pull gently on the needles. “You’re the one everyone can count on for help.”

He rests his arms on the wall of his truck bed. “Does that surprise you?”

He’s testing me because he knows I’ve heard something about him. And he’s right to test me, because I’m not sure how to answer. “Should it surprise me?”

He looks down at his trees, and I can tell he’s disappointed that I dodged the question.

“I assume these trees aren’t all for you,” I say.

He smiles.

I lean forward, not sure if I should be doing this, but also feeling compelled. “Well, if you plan to buy any more, I know the owners at the other lot fairly well. I think I can get you a discount.”

He takes out his wallet, again stuffed with one-dollar bills, and pulls out a few singles. “Actually, I’ve been there two times since I saw you hanging that parade sign, but you were out.”

Was that an admission that he had hoped to see me? I can’t ask that, of course, so I point to his wallet. “You know, banks will let you exchange all those ones for something bigger.”

He turns the wallet over in his hands. “What can I say, I’m lazy.”

“At least you know your flaws,” I say. “That’s healthy.”

He shoves the wallet in his pocket. “Knowing my flaws is one thing I’m good at.”

If I were bolder, I would use that as an opening to ask about his sister, but a question like that could so easily send him into his truck, driving away.

“Flaws, huh?” I take a step closer to him. “Buying all these trees and helping people move, you must be at the top of Santa’s naughty list.”

“If you put it that way, I guess I’m not all bad.”

I snap my fingers. “You probably consider your sweet tooth a major sin.”

“No, I don’t remember that one being mentioned in church,” he says. “But laziness has been, and I am that. I still haven’t replaced the comb I lost a few months ago.”

“And look at the results,” I say, eyeing his hair. “That’s almost unforgivable. You may need to peruse elsewhere for discounted trees.”

“Peruse?” he says. “I mean, it’s a good word, but I don’t think I’ve used it in a sentence before.”

“Oh, please don’t tell me you consider that a big word.”

He laughs, and his laugh is so perfect I want to continue drawing it out of him. But this comfort in our teasing isn’t good. Regardless of how cute he is, or easy to joke with, I have to remember Heather’s concern.

As if he can see the thoughts turning in my mind, his face turns resentful. His gaze falls back to the trees. “What?” he asks.

If we keep running into each other, there will always be a conversation—this rumor—hanging over us.

“Look, obviously I heard something…” The words dry up in my throat. But why do I need to say them? We can just go back to being the customer and the tree girl. This does not need to come up.

“You’re right, it’s very obvious,” he says. “It always is.”

“But I don’t want to believe it if—”

He pulls his keys out of his pocket and still won’t look at me. “Then don’t worry about it. We can be nice to each other, I’ll buy my trees from you, but…” His jaw clenches. I can tell he’s trying to raise his eyes to look at me, but he can’t.

There is nothing more I can say. He hasn’t told me that what I’ve heard is a lie. The next words need to come from him.

He moves to the cab of his truck, gets in, and pulls the door shut.

I step back.

He starts the engine and then gives me a small wave as he drives off.

CHAPTER EIGHT

I don’t start work until noon on Saturday, so Heather picks me up early and I ask her to take us to Breakfast Express. She looks at me strangely but drives in that direction.

“Did you find out if you can go to the parade with us?” she asks.

“It shouldn’t be a problem,” I say. “The whole town goes to that thing. We won’t be swamped until after it ends.”

I think about the sad wave Caleb offered when he drove off last night and the weight on his shoulders that kept him from looking at me. Even if there are reasons not to get involved, I still want to see his truck drive up to the lot again.

“Devon thinks you should ask Andrew to the parade,” Heather says. “Now, I know what you’re going to say…”

I’m thankful my eyeballs don’t pop out onto her dashboard. “Did you tell Devon that’s a terrible idea?”

She lifts a shoulder. “He thinks you should give him a chance. I’m not saying I agree with him, but Andrew does like you.”

“Well, I completely don’t like him.” I scrunch down in my seat. “Wow. That sounded so mean.”

Heather pulls up to the curb in front of Breakfast Express, a 1950s-themed diner housed in two retired train cars. One car is the diner and the other is the kitchen. Beneath both cars, the steel wheels are anchored to actual rails set over splintered wooden ties. Best of all, they serve breakfast—only breakfast—all day long.

Before she turns off the engine, Heather looks past me to the windows of the train cars. “Look, I wasn’t going to say no to this because I know you love coming here.”

“Okay,” I say, unsure what that was all about. “If you want to go somewhere else—”

“But before we go in,” she says, “you should know that Caleb works here.” She waits for that to sink in, and it sinks down like a rock.

“Oh.”

“I don’t know if he’s working today, but he may be,” she says. “So figure out how you’re going to be.”

While approaching the stairs to the diner car, my heart beats faster and faster the closer I get. I follow Heather up the steps, and she pulls open the red metal door.

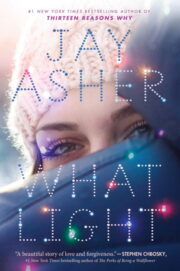

"What Light" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "What Light". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "What Light" друзьям в соцсетях.