That first night, I cried and bit my fingers and drank wine I snuck from the Clairmont pantry. I spun violently into the sky, raging and banging stars from their moorings, swirling and vomiting.

I hit my fist into the wall of the shower. I washed off the shame and anger in cold, cold water. Then I shivered in my bed like the abandoned dog that I was, my skin shaking over my bones.

The next morning, and every day thereafter, I acted normal. I tilted my square chin high.

We sailed and made bonfires. I won the tennis tournament.

We made vats of ice cream and lay in the sun.

One night, the four of us ate a picnic down on the tiny beach. Steamed clams, potatoes, and sweet corn. The staff made it. I didn’t know their names.

Johnny and Mirren carried the food down in metal roasting pans. We ate around the flames of our bonfire, dripping butter onto the sand. Then Gat made triple-decker s’mores for all of us. I looked at his hands in the firelight, sliding marshmallows onto a long stick. Where once he’d had our names written, now he had taken to writing the titles of books he wanted to read.

That night, on the left: Being and. On the right: Nothingness.

I had writing on my hands, too. A quotation I liked. On the left: Live in. On the right: today.

“Want to know what I’m thinking about?” Gat asked.

“Yes,” I said.

“No,” said Johnny.

“I’m wondering how we can say your granddad owns this island. Not legally but actually.”

“Please don’t get started on the evils of the Pilgrims,” moaned Johnny.

“No. I’m asking, how can we say land belongs to anyone?” Gat waved at the sand, the ocean, the sky.

Mirren shrugged. “People buy and sell land all the time.”

“Can’t we talk about sex or murder?” asked Johnny.

Gat ignored him. “Maybe land shouldn’t belong to people at all. Or maybe there should be limits on what they can own.” He leaned forward. “When I went to India this winter, on that volunteer trip, we were building toilets. Building them because people there, in this one village, didn’t have them.”

“We all know you went to India,” said Johnny. “You told us like forty-seven times.”

Here is something I love about Gat: he is so enthusiastic, so relentlessly interested in the world, that he has trouble imagining the possibility that other people will be bored by what he’s saying. Even when they tell him outright. But also, he doesn’t like to let us off easy. He wants to make us think—even when we don’t feel like thinking.

He poked a stick into the embers. “I’m saying we should talk about it. Not everyone has private islands. Some people work on them. Some work in factories. Some don’t have work. Some don’t have food.”

“Stop talking, now,” said Mirren.

“Stop talking, forever,” said Johnny.

“We have a warped view of humanity on Beechwood,” Gat said. “I don’t think you see that.”

“Shut up,” I said. “I’ll give you more chocolate if you shut up.”

And Gat did shut up, but his face contorted. He stood abruptly, picked up a rock from the sand, and threw it with all his force. He pulled off his sweatshirt and kicked off his shoes. Then he walked into the sea in his jeans.

Angry.

I watched the muscles of his shoulders in the moonlight, the spray kicking up as he splashed in. He dove and I thought: If I don’t follow him now, that girl Raquel’s got him. If I don’t follow him now, he’ll go away. From the Liars, from the island, from our family, from me.

I threw off my sweater and followed Gat into the sea in my dress. I crashed into the water, swimming out to where he lay on his back. His wet hair was slicked off his face, showing the thin scar through one eyebrow.

I reached for his arm. “Gat.”

He startled. Stood in the waist-high sea.

“Sorry,” I whispered.

“I don’t tell you to shut up, Cady,” he said. “I don’t ever say that to you.”

“I know.”

He was silent.

“Please don’t shut up,” I said.

I felt his eyes go over my body in my wet dress. “I talk too much,” he said. “I politicize everything.”

“I like it when you talk,” I said, because it was true. When I stopped to listen, I did like it.

“It’s that everything makes me …” He paused. “Things are messed up in the world, that’s all.”

“Yeah.”

“Maybe I should”—Gat took my hands, turned them over to look at the words written on the backs—“I should live for today and not be agitating all the time.”

My hand was in his wet hand.

I shivered. His arms were bare and wet. We used to hold hands all the time, but he hadn’t touched me all summer.

“It’s good that you look at the world the way you do,” I told him.

Gat let go of me and leaned back into the water. “Johnny wants me to shut up. I’m boring you and Mirren.”

I looked at his profile. He wasn’t just Gat. He was contemplation and enthusiasm. Ambition and strong coffee. All that was there, in the lids of his brown eyes, his smooth skin, his lower lip pushed out. There was coiled energy inside.

“I’ll tell you a secret,” I whispered.

“What?”

I reached out and touched his arm again. He didn’t pull away. “When we say Shut up, Gat, that isn’t what we mean at all.”

“No?”

“What we mean is, we love you. You remind us that we’re selfish bastards. You’re not one of us, that way.”

He dropped his eyes. Smiled. “Is that what you mean, Cady?”

“Yes,” I told him. I let my fingers trail down his floating, outstretched arm.

“I can’t believe you are in that water!” Johnny was standing ankle-deep in the ocean, his jeans rolled up. “It’s the Arctic. My toes are freezing off.”

“It’s nice once you get in,” Gat called back.

“Seriously?”

“Don’t be weak!” yelled Gat. “Be manly and get in the stupid water.”

Johnny laughed and charged in. Mirren followed.

And it was—exquisite.

The night looming above us. The hum of the ocean. The bark of gulls.

8

THAT NIGHT I had trouble sleeping.

After midnight, he called my name.

I looked out my window. Gat was lying on his back on the wooden walkway that leads to Windemere. The golden retrievers were lying near him, all five: Bosh, Grendel, Poppy, Prince Philip, and Fatima. Their tails thumped gently.

The moonlight made them all look blue.

“Come down,” he called.

I did.

Mummy’s light was out. The rest of the island was dark. We were alone, except for all the dogs.

“Scoot,” I told him. The walkway wasn’t wide. When I lay down next to him, our arms touched, mine bare and his in an olive-green hunting jacket.

We looked at the sky. So many stars, it seemed like a celebration, a grand, illicit party the galaxy was holding after the humans had been put to bed.

I was glad Gat didn’t try to sound knowledgeable about constellations or say stupid stuff about wishing on stars. But I didn’t know what to make of his silence, either.

“Can I hold your hand?” he asked.

I put mine in his.

“The universe is seeming really huge right now,” he told me. “I need something to hold on to.”

“I’m here.”

His thumb rubbed the center of my palm. All my nerves concentrated there, alive to every movement of his skin on mine. “I am not sure I’m a good person,” he said after a while.

“I’m not sure I am, either,” I said. “I’m winging it.”

“Yeah.” Gat was silent for a moment. “Do you believe in God?”

“Halfway.” I tried to think about it seriously. I knew Gat wouldn’t settle for a flippant answer. “When things are bad, I’ll pray or imagine someone watching over me, listening. Like the first few days after my dad left, I thought about God. For protection. But the rest of the time, I’m trudging along in my everyday life. It’s not even slightly spiritual.”

“I don’t believe anymore,” Gat said. “That trip to India, the poverty. No God I can imagine would let that happen. Then I came home and started noticing it on the streets of New York. People sick and starving in one of the richest nations in the world. I just—I can’t think that anyone’s watching over those people. Which means no one is watching over me, either.”

“That doesn’t make you a bad person.”

“My mother believes. She was raised Buddhist but goes to Methodist church now. She’s not very happy with me.” Gat hardly ever talked about his mother.

“You can’t believe just because she tells you to,” I said.

“No. The question is: how to be a good person if I don’t believe anymore.”

We stared at the sky. The dogs went into Windemere via the dog flap.

“You’re cold,” Gat said. “Let me give you my jacket.”

I wasn’t cold but I sat up. He sat up, too. Unbuttoned his olive hunting jacket and shrugged it off. Handed it to me.

It was warm from his body. Much too wide across the shoulders. His arms were bare now.

I wanted to kiss him there while I was wearing his hunting jacket. But I didn’t.

Maybe he loved Raquel. Those photos on his phone. That dried beach rose in an envelope.

9

AT BREAKFAST THE next morning, Mummy asked me to go through Dad’s things in the Windemere attic and take what I wanted. She would get rid of the rest.

Windemere is gabled and angular. Two of the five bedrooms have slanted roofs, and it’s the only house on the island with a full attic. There’s a big porch and a modern kitchen, updated with marble countertops that look a little out of place. The rooms are airy and filled with dogs.

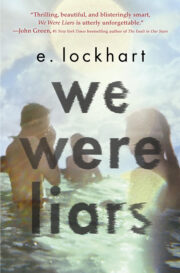

"We Were Liars" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "We Were Liars". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "We Were Liars" друзьям в соцсетях.