He bit back a sarcastic retort; she never reacted well to such rejoinders from him. He nodded. “Close the window and go back to bed — I’ll see you tomorrow.”

She stepped forward and slid the sash carefully down. She remained behind the pane for a moment, then turned and glided away.

He looked down — manfully resisting the temptation to peek when she doffed the coverlet and climbed between the sheets — and started on his journey back to the ground.

Although more or less disgusted, certainly disgruntled with how matters had played out, as he backed down the wall, hand below hand, foot by foot, he had to admit to a lurking but very real respect for her stance.

Family mattered.

Few appreciated that better than he. He who had no true blood kin. His biological father had been the late Camden Sutcliffe, diplomat extraordinaire — womanizer extraordinaire, as well. His mother had been the Countess of Brunswick, who had borne her husband two daughters, but no son. Brunswick had from the first claimed Breckenridge as his own — initially out of relief arising from his desperate need of an heir, but later from true affection.

It was Brunswick who had taught Breckenridge about family. Breckenridge rarely used his given name, Timothy; he’d been Breckenridge from birth and thought of himself by that name, the name carried by the Earl of Brunswick’s eldest son. Because that’s who he’d always truly been — Brunswick’s son.

So he fully comprehended Heather’s need to learn what was behind the strange abduction, given that it had been targeted not specifically at her but at her sisters, and possibly her cousins, as well.

He himself had two older sisters, Lady Constance Rafferty and Lady Cordelia Marchmain. He frequently referred to them as his evil ugly sisters, yet he’d slay dragons for either, and despite their frequent lecturing and hounding, they loved him, too. Presumably that was why they lectured and hounded. God knew it wasn’t for the results.

Nearing the ground, he swung his legs back from the wall, released the pipe, and dropped to the gravel at the side of the inn. He’d bribed the innkeeper to tell him which room he’d put the pretty lady in; still clad in his evening clothes, it hadn’t been hard to assume the persona of a dangerous rake.

Straightening, he stood for a moment in the chill night air, mentally canvassing all he needed to do. He would have to swap the phaeton for something less noticeable, but he’d keep the grays, at least for now. Glancing down at his clothes, he winced. They would have to go, too.

With a sigh, he set out to walk the short distance to the small tavern down the road at which he’d hired a room.

High above, Heather stood peering out of the window. She saw Breckenridge stride away and let out a sigh of relief. She hadn’t been able to see him until he’d walked away from the wall; she’d been waiting, watching, worried he might have slipped and fallen.

She might not like him — not at all — and she certainly didn’t appreciate his dictatorial ways, but she wouldn’t want him hurt, especially not when he’d come to rescue her. She might have decided against being rescued yet, but she wasn’t so foolish as to reject his help. His support. Even, if it came to it, his protection — in the perfectly acceptable sense.

His abilities in that regard would be, she suspected, not to be sneezed at.

Still, she found it odd that the instant she’d recognized him outside the window, confidence and certainty had infused her. In that moment, all her earlier trepidation had fled.

Inwardly shrugging, she turned from the window. Assured, more resolute, infinitely more certain the path forward she’d chosen was the right one, she padded back to the bed, flicked the coverlet back over the sheets, slipped beneath, and laid her head on the pillow.

Smiled at the memory of Breckenridge’s expression when he’d gestured at her to open the window; he hadn’t been his usual impassive self then. Amused, relieved, she closed her eyes and slept.

Chapter Three

The next morning, relatively early, Heather found herself back in the coach and heading north once more.

Martha had woken an hour after dawn and consented to hand Heather the round gown of plain green cambric they’d brought for her to wear. Heather had retrieved her fringed silk shawl, but her amber silk evening gown and her small evening reticule had been packed into Martha’s commodious satchel. Martha’s planning hadn’t extended to footwear. With the woolen cloak about her and her evening slippers on her feet, Heather had been escorted downstairs to a private parlor.

Over breakfast, taken with Fletcher, Cobbins, and the hatchet-faced Martha, Heather had had no chance to even make eye contact with the busy serving girls. If anyone did come asking after her, she doubted that the overworked girls would even remember her.

While she’d eaten, she’d thought back over her behavior in the carriage the previous night. Although she’d asked questions, she hadn’t given her captors any reason to believe she was the sort of young lady who might seriously challenge them or disobey their orders. Admittedly she hadn’t burst into tears, or wrung her hands and sobbed pitifully, but they’d been warned she was clever, so they shouldn’t have expected that.

Although it had gone very much against her grain, by the time they’d risen and she’d been ushered, under close guard, into the waiting coach, she’d decided to play to their apparent perceptions, to appear malleable and relatively helpless despite her supposed intelligence. Her plan, as she’d taken her seat on the forward-facing bench once more, was to lull the trio into viewing her much as a schoolgirl they were escorting home.

In the few minutes while she, Martha, and Cobbins had waited in the coach for Fletcher to finish with the innkeeper and join them, she’d looked out of the coach window and seen an ostler holding a prancing bay gelding, saddled and waiting for its rider.

The temptation to open the coach door, jump down, race the few feet to the horse, grab the reins, mount, and thunder back down the road toward London had flared — and just as quickly had died. Not only would the maneuver have been fraught with risk — with no money or possessions, let alone proper clothes, she might have potentially jumped from frying pan into fire — but, successful or not, it would have ensured she got no chance to learn more about what lay behind her abduction.

She’d decided she would have to rely on Breckenridge, have to count on him following her. She’d wondered if he’d yet risen from his bed. He was one of the foremost rakes of the ton; such gentlemen were assumed to see little of the morning, certainly not during the Season.

Then Fletcher had climbed in, shut the door, and the coach had jerked, rumbled forward, and turned north — and she’d discovered that trusting in Breckenridge wasn’t all that hard. Some part of her had already decided to.

She bided her time, lulling her three captors as planned, letting a silent hour pass as the miles slid by. She waited until sufficient time had elapsed to allow her to lean forward, peer out, and somewhat peevishly inquire, “Is it much farther?”

She looked at Fletcher, but he only grinned. The other two, when she glanced questioningly at them, simply closed their eyes.

Looking again at Fletcher, she frowned. “You might at least tell me how long I’ll be cooped up in this carriage.”

“For some time yet.”

She opened her eyes wide. “But won’t we be stopping for morning tea?”

“Sorry. That’s not on our schedule.”

She looked horrified. “But surely we’ll be stopping for lunch?”

“Lunch, yes, but that won’t be for a while.”

Adopting a put-upon expression, she subsided, but “stopping for lunch” suggested they would be heading on afterward. She debated, then asked, “How far north are you taking me?” She made her voice small, as if the thought worried her. Which it did.

Fletcher considered her but volunteered only, “A ways yet.”

She let another mile or two slide by before restlessly shifting, then asking, “This employer of yours — do you normally work for him?”

Fletcher shook his head. “We work for hire, me and Cobbins, and as we’ve known Martha forever, she agreed to assist us.”

“So he approached you?”

Fletcher nodded.

“Where did you meet him?”

Fletcher grinned. “Glasgow.”

She met Fletcher’s eyes, grimaced, and fell silent again. She’d eat her best bonnet if either Fletcher or Cobbins hailed from north of the border, and from her accent, Martha was definitely a Londoner. . did that mean the man who’d hired them was Glaswegian?

Were they actually imagining taking her over the border?

Heather longed to ask, but Fletcher was watching her with a faintly taunting smile on his face. He knew her questions weren’t idle, which meant he’d tell her nothing useful. At least, not intentionally.

Yet from what he’d let fall, she had at least until sometime after lunch to quiz him and the others. Folding her arms, she closed her eyes and decided to lull him some more.

There were really only two answers she needed before she escaped — who had hired them, and why.

She opened her eyes when the houses of St. Neots closed around the coach. They passed a clock tower, the dial of which confirmed it was only midmorning. Stretching, she surveyed the view outside, then settled back and fixed her gaze on Fletcher. “Have you and Cobbins always worked together?”

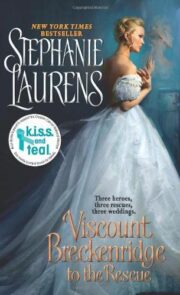

"Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue" друзьям в соцсетях.