Ridiculous in a way, but who would have thought her foot could be so sensitive? So sensitive in such a very improper way?

She was still dwelling on the revelation when he escorted her from the shop, back into the midafternoon bustle.

As they started along again, merging with the shoppers, he lowered his head and grumbled, “Didn’t Martha have the sense to provide you with thicker hose?”

She nodded. “But they were so coarse I couldn’t bear to wear them — they scratched.”

Breckenridge fleetingly closed his eyes. The image her words conjured — of the finest, most delicate silken skin lining sleek, feminine inner thighs — wasn’t one he needed to dwell on.

Opening his eyes, he looked ahead, then nudged her toward another alley. “There’s two constables wandering slowly this way. We’ll have to go around.”

The street they came out on was lined with market stalls selling all manner of fresh produce. They exchanged a glance, then he stood watch while she selected and bargained for apples, some dried fruits, a loaf of seed bread, and a large bag of nuts. He saw a stall selling water skins and added one to their haul. Satchels bulging, they continued on, keeping a wary eye out for ambling constabulary.

They eventually found themselves on Buccleuch Street. “We should get off the pavements.” He nodded toward the window of a coffeehouse opposite. “Let’s go in there and check the map, and work out our best way forward.”

Crossing the street, they entered the coffeehouse, which proved to be quite large and helpfully ill lit. Heather led the way to a table in the shadows along one wall and toward the rear.

A girl came bustling up. He ordered coffee, and after some discussion, Heather ordered a pot of tea and two large plates of scones.

He arched a brow as the girl departed. “Still hungry?”

Heather shrugged. “I’m sure their jam and scones will be lovely — country-made usually are.” She suddenly looked conscious, then fixed her eyes on his. “We have enough money, don’t we? I mean, don’t you?”

He nearly laughed at her look, then waved. “Plenty. I got more when I stopped in Carlisle. Money isn’t on our list of concerns.”

“Good.” She propped her chin in one palm and met his eyes across the table. “We have concerns enough as it is.”

He nodded. “How are the boots?”

“Quite good. He was right, the cobbler. They are well made.”

“All right. So. .” He pulled the map from his coat pocket, unfolded, then refolded it so the section they needed was exposed. He set it against the wall between them, so they could both see it. “We’re here.” He pointed to Dumfries. “And Carsphairn — the village — is there. How to get from here to there is what we need to decide.”

The girl returned with his coffee, Heather’s tea, and two plates piled high with buttery scones. For ten minutes, they were silent, but after polishing off his second scone loaded with blackberry jam and cream, he picked up his coffee mug, sipped, and returned his attention to the map. “Nice scones.”

“Hmm.”

The sound made his lips twitch. It was one of the things he was learning to like about her; she appreciated the small pleasures.

How she would react to larger, more intense pleasures. .

He blinked, and forced himself to refocus on the map. “Let’s list all our options first. We could hire a gig and drive — the most obvious way to get from here to there.”

Heather poked a bit of jam-laden scone past her lips. “Or we could hire horses and ride — and if we did that, we could go cross-country, not by the major roads. We could take this route.” With one fingertip she traced a minor road — more like a country lane — that went across and over the hills.

He considered it. “That route looks shorter, but it’ll almost certainly take longer because of the climbing and switching back and forth through the passes. Against that, it will almost certainly be free of patrolling constables, and at this time of year, there’s little likelihood of the passes being blocked — the way should be clear.”

Heather took a long, revivifying sip of her tea, then sighed and set down the cup. “But we can’t risk hiring a gig or any carriage, not even horses, can we?”

Breckenridge met her eyes, then grimaced. “I’ve been toying with the notion, but I can’t see how to do it without leaving some trace. The constabulary isn’t foolish — they’ll have alerted all the stables. And we have to assume we have the mysterious laird on our heels, too. He must have arrived in Gretna by now. We can’t afford to assume we’re free of him, and he’ll certainly check every possible place we might try to hire from.”

Heather nodded briskly. “If we can’t hire horses, then we’ll have to walk.”

Breckenridge hesitated, his eyes on hers, then quietly asked, “Are you up for that?”

Not, she noted, could she manage that; he really was remarkably attuned to women.

Suppressing a smile, she nodded. “I walk quite a lot when at home. These hills may be higher than the Quantocks, but they’re not horribly mountainous, either. I’ll manage.”

He looked at her, then said, “If you can, then I’d prefer to play safe — to do everything we possibly can to avoid both the constables and the laird if he’s searching. How long it takes us to get to the Vale is less important than that we reach there safely.”

She nodded again. “I agree. For us, the less-traveled way, the least likely way, is the best option.”

He reached for the map. “The country lanes, then.” He consulted the map, then said, “We need to head out on the main road to Glasgow. The road we want gives off that a mile or two out of town.”

She looked past him, out through the front window of the coffee shop. “The light’s starting to wane. We should go.”

They drained their mugs. Crumbs were all that was left of the scones.

The girl came to take their payment.

“Which is the road to Glasgow?” Breckenridge asked.

The girl pointed right. “Go straight along the street, across the bridge over the river, then turn right. You can’t miss it.”

Breckenridge thanked her and left a small tip — the sort an unemployed solicitor’s clerk might leave.

The girl bobbed and, smiling, showed them out.

Stepping into the street, Breckenridge saw two constables walking the pavement, but by fate’s blessing they had their backs to them and were walking away from them, away from the bridge over the river. “Come on.” He’d already taken Heather’s hand. He glanced at her head, at the shawl she had slung about her shoulders. “Can you wind the shawl about your hair? It’ll make you a trifle less recognizable.”

She drew her hand from his and complied.

Then she reached for his hand again, just as he reached for hers.

Together, hand in hand, side by side, they walked steadily, resisting a very real urge to hurry, along the street, across the bridge, and out of Dumfries.

The highlander calling himself McKinsey rode into Dumfries an hour later. The first thing he noted as he walked Hercules along, heading toward High Street, was a number of constables either watching the main road or patrolling the pavements on foot.

The constables were searching for a girl. He, however, was searching for a couple.

He’d found their tracks in the fields immediately southeast of the town, had seen where they’d veered to join the road leading into the town proper. He debated sharing his insight with the constables but decided against it. The constables here most likely wouldn’t know that it was he who had instigated their search, which would necessitate detailed explanations, but more importantly, should he find the girl and the bounder she was with, he wanted to be free to deal with the man in his own way — silently and anonymously.

Turning off the main street into the yard of the Globe Inn, he left Hercules safe in the stable and headed on foot into the warren of streets that formed the center of the town.

He was Scottish; he could ask questions and, by and large, people would happily answer. All he needed to do was allow a touch of his native brogue to slide into his voice.

He’d found the barn where the fugitive pair had spent the night. He’d tracked them steadily on; somewhat to his surprise they hadn’t stopped at any village, not even in Annan, to eat. From what he’d understood of how they’d left the inn at Gretna Green, they shouldn’t have had any food with them. Which meant that by now, they should be dizzy with hunger.

Eating would be at the top of their list of things to do in Dumfries. As it was market day, the town would have been crowded throughout the day; they would have had excellent cover. More than enough to avoid the notice of the constables patrolling the streets.

From their tracks, he estimated that the pair had entered the town at least three, possibly four hours ahead of him. Starting at the lower end of High Street, he stopped at every eatery and asked after his brother and his lass, explaining that he’d missed them and was trying to catch them up; from what he’d learned of Timms, the relationship would pass well enough.

He struck gold early at the Old Wall Tavern just off High Street. The serving girl couldn’t tell him anything about the pair’s eventual direction, but she sent him to the cobbler a little further north along the main street. There, he learned of their purchase. Remembering the girl’s slippers, he wasn’t surprised, but he couldn’t decide whether the purchase of walking boots specifically implied anything.

The cobbler, when applied to, shrugged. “Only pair I had in her size, so it could have just been that that made her choose them.” A second later, the old man grinned. “Mind you, you should warn your brother — he’s been living in Lunnon too long. Charged ’im the full Lunnon price, I did, and he didn’t turn a hair. Just pulled out the coins and handed them over. Not short of the ready, is he?”

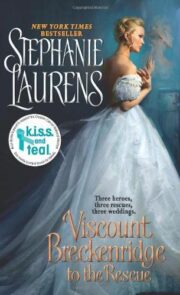

"Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue" друзьям в соцсетях.