Despite not getting what she’d wanted, the knowledge made her feel more content.

They walked into a sunset muted by churning clouds. Before the encroaching darkness deepened, Breckenridge paused to check the map.

“We should be nearly at Dornock.” He looked ahead, squinted. “I can see roofs ahead — that must be the village.”

“We can’t just walk up and ask for shelter, can we?” She’d thought through the ramifications. “Those riders would have stopped and warned the villagers about us — about me, at least.”

He grunted an assent. He surveyed the still largely flat fields, then touched her arm, pointed a little way further south. “There’s a barn there, close enough to reach before the light fails. Let’s see what it’s like.”

She didn’t reply, merely started walking.

Tucked in one corner of a field, isolated and at least three fields from the nearest farmhouse, the barn proved sound and filled with hay. Much of it was loose, and the fragrance that surrounded them when they climbed to the loft was redolent with the memory of summer.

Breckenridge looked around. “We’ll be warm enough up here, and safe enough.” He glanced down at the ladder they’d climbed up. “The ladder isn’t fixed — I’ll pull it up for the night.”

So she’d feel safe. Heather hid a grin; for a man whose expression she could still rarely read, he was becoming quite predictable in some ways.

Setting down her satchel, she slipped off her cloak, flicked it out, and spread it over a wide, deep pile of hay, then turned and sat, wriggling her hips to create a comfortable hollow. Reaching down, she eased off her poor slippers, studied them in the fading light. “I don’t suppose we can risk a fire.”

Looking up, she met Breckenridge’s shadowed eyes.

After a moment, he shook his head. “No. Too risky.”

But he’d thought of it. She nodded and set the slippers aside, used her cloak to rub her feet dry, then stretched out her toes, flexed her ankles, and reached beneath her skirts to massage her calves.

He cleared his throat. “We haven’t any food, either.”

She glanced up, faintly smiled. “I don’t think going without food for one night is going to hurt either of us.”

He held her gaze, after a moment said, “You’re being very accommodating. I was expecting something rather closer to hysterics.”

She snorted. “And what good would they do?” She raised a shoulder. “We’re in this together, and doing the best we can. I don’t expect you to perform miracles.” Lying back on her makeshift pallet, she looked up at him. “And as long as you don’t expect miracles from me, I daresay we’ll manage well enough.”

He stared at her, his expression, as usual, impenetrable. Of all the men she’d ever met, he kept his features under the most rigid control. Then he shrugged off the satchels he’d carried, set them near hers, and turned back toward the ladder. “I’m going to check around the building. I won’t go far, and I won’t be long.”

Heather lay back, let her muscles relax, and tracked him by sound. He moved around within the barn, then went outside.

While she waited, she held onto a mental vision of him — imagined him walking around the structure, assessing it. Her brothers, her cousins, were protective men; she was accustomed to the foibles of the species. Breckenridge, however, although every bit as protective, if not more so, hid it better. She considered, then murmured, “No, that’s not right.” He didn’t so much hide his proclivities as mute them, negotiate around them. Make them seem reasonable and sensible and justifiable.

His was a more subtle, but also more effective, approach.

If he’d been one of her brothers, or even one of her cousins, she’d have felt smothered by now — and she’d have been sniping and resisting his orders and restrictions for all she was worth, on principle if nothing else. But because he was reasonable and listened — or at least seemed to listen — to her wishes, then she could be reasonable, too.

Given her previous view of him, that she’d come to the point of regarding him as “reasonable” struck her as exquisitely ironic.

By the time he returned, darkness had fallen, but the moon was half full, shedding sufficient light to make out shapes even inside the barn. When he reached the top of the ladder, she slid her feet back into her slippers, stood, and shook out her skirts. “I need to go outside. I won’t go far, and I won’t be long.”

He froze. She smiled sunnily at him, even if he probably couldn’t see well enough to appreciate the effect. She’d given him back his own words. She’d trusted him, now he had to trust her.

With obvious reluctance, he shifted, allowing her to reach the head of the ladder. “It’s dark.”

“I’ll be careful.” She started down the ladder, then glanced up at him. “Just stay there.”

Reaching the ground, she walked to the barn door, lit by light slanting down through a window high in one side wall. Pulling open the door, she glanced out, then slipped around the corner of the barn to attend to the call of nature.

She walked back inside five minutes later, only to find him waiting just inside the door. She narrowed her eyes at him, but he didn’t meet her gaze, simply pulled the door closed, then lifted a heavy beam and angled it across the opening.

“If anyone tries to come in, they’ll have to shift that — we’ll hear them.”

She humphed and walked toward the ladder, wondering if he’d thought of the beam before or after he’d followed her down to the ground.

He trailed close behind her, claimed her hand, and helped her onto the ladder. She climbed up, careful not to get her feet tangled in her skirts. Once she stepped free, he followed her up, then turned and, with surprising ease, hauled up the long ladder.

She settled back on her cloak and watched as, bathed in the faint moonlight, he maneuvered the ladder to lay it along the edge of the loft. Even though he was fully clothed, she still got an impression of the play of muscle necessary to achieve such a feat.

There was no denying Breckenridge was one of the ton’s favorite rakes for good reason.

Smiling to herself, she relaxed on her makeshift bed.

He looked at her, then picked up his own cloak, shook it out, and spread it on the hay, not next to her but on the other side of their satchels. She inwardly humphed. While he sat, then lay back and settled, she sat up and pulled her satchel closer. Opening it, she hauled out the other plain gown and her evening gown. The silk, she hoped, would help to keep her warm.

Breckenridge, of course, had simply wrapped his cloak about himself. Given how warm he always seemed to be, he would probably be warm enough. She fussed, laying first the evening gown, then the plain gown over her, then she lay down and wrapped the skirts of her cloak around her.

She was, she told herself, warm enough. She wasn’t likely to freeze.

Breckenridge spoke out of the thickening darkness; the moonlight was starting to fade. “We’ll head for Annan in the morning — see if we can slip into the town, get some breakfast and shoes for you at least.”

“Hmm. I suppose in a town rather than a village we’ll have a better chance of escaping attention.”

He didn’t reply.

“Good night,” he eventually murmured.

“Good night.” Settling her head on one hand, she closed her eyes.

Silence fell.

Whether it was her hearing sharpening once she’d shut her eyes, or that the sounds only began some minutes after she and Breckenridge had become silent and still, rustlings started, at some distance initially, but as the minutes stretched, she could swear the furtive shifting of the hay was growing nearer, and nearer. .

She was suddenly wide awake.

Suddenly in a greater panic than she’d been earlier in the day.

The only thought that occurred to her, the only possible way to secure relief, involved shockingly forward behavior.

To escape mice, she could be shockingly forward.

Rising, all but leaping to her feet, she grabbed up her gowns-cum-covers, swiped up her cloak, and dashed past their mounded satchels to where Breckenridge had stretched out.

Through the dimness she could just make him out, stretched on his back, his arms crossed behind his head. He might have been silent, but he hadn’t been asleep. She could feel his frown as he looked at her.

“What are you doing?”

“Moving closer to you.” Dropping her gowns, she shook out her cloak and laid it next to his.

“Why?”

“Mice.”

He let a heartbeat pass, then asked, carefully, “You’re afraid of mice?”

She nodded. “Rodents. I don’t discriminate.” Swinging around, she sat on her cloak, then picked up her gowns and wriggled back and closer to him. “If I’m next to you, then either they’ll give us both a wide berth, or if they decide to take a nibble, there’s at least an even chance they’ll nibble you first.”

His chest shook. He was struggling not to laugh. But at least he was trying.

“Besides,” she said, lying down and snuggling under her massed gowns, “I’m cold.”

A moment ticked past, then he sighed.

He shifted in the hay beside her. She didn’t know what he did, but suddenly she was sliding the last inches down a slope that hadn’t been there before. She fetched up against him, against his side — hard, muscled, and wonderfully warm.

Her senses leapt greedily, pleasantly shocked, delightedly surprised; she caught her breath and slapped them down. Desperately; this was Breckenridge — this was definitely not the time.

His arm shifted and came around her, cradling her shoulders and gathering her against him.

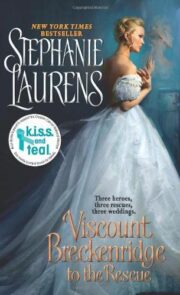

"Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue" друзьям в соцсетях.