Martha looked, then set down her knitting bag and shook out a large rug she’d carried under her arm. Laying it on the grass, she pointed to one end. “Sit you down there, and don’t make me regret taking up for you and getting you out in the fresh air.”

Remembering Breckenridge’s warning not to step out of her assumed character, Heather dutifully subsided. Martha sat, too, and pulled out her knitting.

Although the fresh air was welcome, within ten minutes, Heather was thoroughly bored. The last thing she needed was time to dwell on Breckenridge and the unruly impulses that increasingly came to the fore when he was near.

She definitely didn’t need to think about those, and even less about him, and her steadily changing opinion. It had been much easier to deal with him, and her misguided attraction to him, when she’d thought him a too-handsome-for-his-own-good, far-too-experienced-to-look-in-her-direction, arrogant, indolent, and self-indulgent rake of the first order.

Now. . he might still be all that, but he’d also shown himself to have qualities she knew enough to recognize as admirable. Protective males could be difficult to manage; against that, they were likely to be there when one needed them, and when one was in danger, their presence was comforting. More, he’d shown a — to her — surprising ability to deal with her as a partner. That, she most definitely hadn’t expected, especially from him.

The thought reminded her of what they were both supposed to be assessing that day — means of escape. She glanced at Martha. The older woman’s head was nodding, but she felt Heather’s gaze and looked up.

Heather glanced back at the inn, clearly visible across the fields.

Martha misinterpreted and chuckled. “Oh, don’t worry. He won’t come charging out to drag us back.” Setting down her knitting, Martha, too, looked back at the inn. “Mind you, I’d wager he watched for the first ten minutes or so, but he’ll have seen by now that there’s no risk to you.” Martha waved her arms at the fields around them. “No chance anyone could creep up and steal you away.”

Heaving a huge sigh, Martha lay down full length on her end of the rug. “I’m going to have a nice little nap in this sun. Don’t think to wander off — I’ll know if you move. A very light sleeper, I am.”

Heather stared, speechless, at the woman who slept so soundly every night that she’d never heard Heather slip out of their room, or back in. Heather managed not to shake her head in disbelief, just in case Martha was watching through her lashes. Instead, she drew in a deep breath and looked around with more interest.

Considered the firth, not more than a mile away. Could they possibly escape by water? Surely they could find a fisherman who might. . but no. Travel by small boat at this time of year wouldn’t necessarily be fast — faster than going by land — and she was fairly sure there would be no benefit to them in trying to get closer to Casphairn by sea. The Vale lay well inland, that much she knew.

While Martha’s snores kept the birds at bay, she wondered what possible distraction they might stage. It had to be something to keep Fletcher and Cobbins occupied—

The soft sound of a footstep had her turning quickly, to see Breckenridge quietly walking up. He looked at Martha, then nodded politely at Heather. “This looked like a good place to get some air. Do you mind if I join you?”

Understanding they were to continue to play their fictitious roles, she inclined her head. “If you wish.”

He sat on the grass a little way away. Drawing a map from his pocket, he opened it and spread it out — laying it between them, where she could see it.

Pointing to Gretna, Breckenridge murmured, “I thought I’d work out the best road to Glasgow.”

He’d spoken quietly, but distinctly. He waited, but Martha’s snores didn’t break rhythm.

Looking at Heather, he arched a brow.

Leaning closer, she extended one tapered finger, with it traced the main road from Gretna to Annan and on to Dumfries. There, she halted, lifted her finger while with her eyes she searched further north and west. .

“There,” she breathed, her finger descending to point to a small village.

He looked, then looked up at her questioningly.

“That’s Carsphairn village.” Her words reached him on a thread of sound. “The road to the Vale heads west, less than a mile south of the village.”

He nodded and drew the map closer. He studied the area she’d indicated, then checked the roads between Dumfries to that point. He glanced at Martha, then murmured, “Even though my trap is old and rickety, I should make it in a day.”

She nodded. “Assuming the way is clear.”

He flicked her a glance. “I believe it will be. But I’ll need to get a good night’s sleep.”

She frowned, then turned her head away from Martha and mouthed, “Tonight?”

Certain no one could snore that deeply without being asleep, he risked murmuring, “No meeting. I’m working on our distraction. Be ready tomorrow — I’m not sure exactly when.”

Gathering the map, he stood and refolded it. Sliding it into his pocket, he nodded politely, then turned and walked back to the inn.

Heather didn’t immediately turn and watch him, but when she judged he would be most of the way back, she shifted and looked, and saw him striding along, nearing the stables.

When he disappeared into the inn, she stifled a sigh and faced forward once more. What was he up to? And why was there to be no secret meeting in the cloakroom to look forward to, and to reassure her, that night?

The following twenty-four hours were the longest Heather had ever endured. She slept fitfully, tossing and turning and wondering what Breckenridge was doing. The only reason he would have cancelled their nightly meeting was that he wasn’t going to be in the inn. And if he wasn’t, where the devil was he?

From the moment the new day dawned, she was tense, on pins. This was the day Fletcher expected the laird to arrive — the dangerous, mysterious, highland nobleman who had ordered her kidnapped and brought to Gretna Green. Both Fletcher and Cobbins had taken pains with their ablutions and attire. Even Martha had spruced herself up. Heather felt thoroughly rumpled in comparison, in her dull round gown and clashing shawl, but her appearance didn’t even feature on her list of concerns.

Breckenridge was playing least in sight. He hadn’t been in the tap for breakfast, at least not while she and Martha had been there. Of course Fletcher had insisted they retire to the parlor and remain in seclusion there, so she had no idea if Breckenridge appeared later, but he didn’t join the company for lunch, either. She didn’t dare inquire directly, but to her relief Martha asked Cobbins where their friend was. Cobbins replied that Timms was preparing to leave, to drive on to Glasgow in easy stages.

The information settled her. The Glasgow road wasn’t the one they would take. Laying a false trail was a sound, very Breckenridgelike idea.

The weather had turned bleak, the wind biting. When a group of sailors came into the tap, closely followed by three farmhands, Fletcher ordered her and Martha back to the parlor.

With ill-grace, she went.

An hour later, she was standing before the parlor window and staring across the inn’s graveled forecourt, tempted to bite a nail although she’d broken the habit years ago, when three men came striding swiftly and purposefully down the lane.

They turned into the inn’s forecourt and headed without pause for the front door.

Their uniforms stated they were from the local constabulary.

Their pugnacious expressions declared they were on the trail of some villain.

The first reached the door, opened it, and strode in. His companions followed on his heels.

Heather headed for the parlor door, risks and options colliding in her mind.

Martha looked up at her, frowned warningly.

Reaching the door, Heather signaled her to silence, then mouthed, “Police.”

Martha dropped her knitting. She paled, then leapt up, grabbed the knitting, and shoved it into her cloth bag.

At the door, Heather carefully cracked it open a sliver. She’d already jettisoned the idea of flinging herself on the constables’ mercy; Fletcher and his story, backed up by Cobbins and Martha, were simply too believable. But what the devil was going on?

Martha joined her at the door, locking large, strong fingers around one of Heather’s wrists.

Heather didn’t look at her, just breathed, “Sssh.”

Through the narrow gap, she peeked into the inn’s front hall. Alongside her, Martha crouched and peeked, too.

The man who’d led the charge into the inn was standing at the bottom of the stairs, talking rapidly, but quietly, with the innkeeper. The two clearly knew each other — hardly surprising in such a small village. The other two constables had taken up positions with their backs to the front door.

A crowd of patrons from the taproom, Fletcher and Cobbins among them, had left their pints and come to cluster in the archway separating the front hall from the tap.

The innkeeper nodded to the first policeman, then came hurrying across to his counter, a little to the side of the parlor door.

Heather couldn’t see what he was doing, but from the sound of pages flipping, she could tell he was consulting his register.

The senior constable turned to scowl at the men crowding the tap’s entrance. “You lot just sit yourselves back down. We want no bother from you.”

Several brows were raised, but the men slowly turned and went back into the tap. After sending intense, searching glances toward the parlor, Fletcher and Cobbins retreated with the pack.

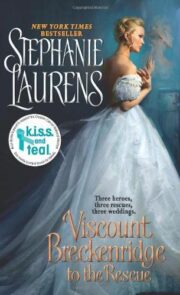

"Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Viscount Breckenridge to the Rescue" друзьям в соцсетях.