The doctor tapped him on the arm. “There’s your future,” he said. “If the new Parliament cares little for ornamental gardens, they care a great deal for the richness of the lands. If we are to keep the Levelers from turning us out of our own doors then we have to feed the people from the acres we have under the plow. The country has to be fed, the country has to find peace and prosperity. If you could write a pamphlet about how it could be done then Parliament would reward you.” He hesitated. “And it would mean that you were seen to be working for the good of Parliament and the army and the people,” he said. “No bad thing, now that your old master is gone.”

John raised an eyebrow. “Any news of the prince?”

“Charles Stuart,” Wharton corrected him gently. “In France, I hear. But with Cromwell in Ireland he might try a landing. He could try a landing at any time and he would always muster an army of a couple of hundred fools. There will always be fools ready to run to a royal standard.”

He paused to see if John disagreed that Charles would only be served by an army of fools. John took meticulous care to say nothing.

“He’s called Charles Stuart now,” Dr. Wharton reminded him.

John grinned. “Aye,” he said. “I’ll remember.”

In April John Lambert strolled into the garden with a smile for Joseph, the gardener, and a low bow for Hester.

“General Lambert!” she exclaimed. “I thought you were at Pontefract.”

“I was,” he said. “But my business there is done. I am to spend the next few months in London, staying at my father-in-law’s house with my family, so I have come to spend the fruits of victory. He only has a little garden so I must not be tempted by one of your great trees. Has Mr. Tradescant anything new?”

“Come and see,” Hester said, and led the way out through the glass doors to the terrace and down to the garden. “The tulips are at their very best. We could let you have some in bud in pots. You will be missing your own at Carlton Hall.”

“I might catch them at the end of their bloom. We have a later season in Yorkshire.”

They walked together to the front of the house and Hester paused to enjoy his delight at the sight of the tulips in bloom in the big double beds before the house.

“Every year I catch my breath,” he said. “It’s like a sea of color.”

Hester smoothed her apron over her hips. “I know,” she said contentedly.

“And what novelties d’you have?” John Lambert asked eagerly. “Anything new?”

“A satin tulip, from Amsterdam,” Hester said, temptingly lifting up a pot. “Look at the shine on it.”

He took the pot in his arms, careless of his velvet jacket and the rich lace at his throat. “What a beauty!” he said. “The petals are like a mirror!”

“And here comes my husband,” Hester remarked, curbing her irritation that John was pushing a barrow up from the seed beds in his shirtsleeves with his hat set askew on his head.

Lambert carefully replaced the pot on its stand.

“Mr. Tradescant.”

John set down the barrow, came up the steps to the terrace, and bowed to their guest. “I won’t shake hands. I’m dirty.”

“I’m admiring your tulips.”

John nodded. “Any luck with your own? Hester told me you were going to try with the Violetten?”

“I have been too much away from home to select the blooms for breeding them to a true color. But my wife tells me they made a pretty show in shades of mauve and purple.”

Farther down the orchard Hester saw Johnnie glance up the avenue and then, when he saw that it was Lambert, pick up his watering pot and with assumed nonchalance stroll up the path under the dark sticky buds of the horse chestnut trees.

“Good day to you,” General Lambert said.

Johnnie skidded to a halt and gave a little bow.

“General Lambert is looking for something for his father-in-law’s garden in Kensington,” Hester said to her husband. “I am tempting him with the new tulip.”

“Isn’t it fine?” John said. “It’s got a sheen on it like, the coat of a bay horse. Does your father-in-law have fruit trees? And you could risk transplanting roses if we do it at once.”

“I’d like some roses,” Lambert said. “He has some Rosamund roses already. D’you have any in pure white?”

“I have a Rosa alba,” John said. “And an offshoot which I have grown from it with very thick petals.”

“Scented?”

“A very light scent, very sweet. And I have a Virginian rose, there’s only two of them in the whole country.”

“And we have a white dog rose,” Johnnie volunteered. “Since you’re a Yorkshireman, sir.”

Lambert laughed. “That’s a pretty thought, I thank you.” He glanced at Johnnie and then looked again. “Hey now, young man, have you been sick? You’re not as bright as when I last saw you.”

There was an awkward silence. “He was in the war,” Hester said honestly.

Lambert took in the slope of Johnnie’s shoulders and the droop of his fair head. “Where was that, lad?”

“At Colchester.”

The general nodded. “A bad business,” he said shortly. “You must be sorry for how it all ended; but thank God we should have peace now, at last.”

Johnnie shot a swift look at him. “You weren’t there for his trial,” he remarked.

Lambert shook his head. “I was doing my duty elsewhere.”

“Would you have tried him?”

Hester moved forward to hush Johnnie but Lambert stopped her with a little gesture of his hand. “Let the lad speak,” he said. “He has a right to know. We are making the country he is going to inherit, he should be able to ask why we made our choices.”

“Would you have found him guilty and had him executed, sir?”

Lambert thought for a moment and then glanced at John. “May I talk with the boy?”

John nodded and Lambert slid an arm around Johnnie’s shoulders and the two of them fell into a stroll, down the little avenue under the resolute strong twigs of horse chestnut and then onward into the orchard under the bobbing, budding boughs of apple, cherry, apricot and plum.

“I wouldn’t have signed his death warrant on the evidence of the trial,” Lambert said softly to Johnnie. “I thought the trial was mismanaged. But I would have worked with all my power to make him recognize that the king must accept some limits. The difficulty with him was that he was a man who would not recognize any limits.”

“He was the king,” Johnnie said stubbornly.

“No one’s denying it,” the older man replied. “But look around you, Johnnie. The people of this country have starved while their lords and their kings have grown fat on their labor. There is no justice for them against any man greater than themselves. The profits of running the state, the taxes, all the trade, were in the gift of the king and scattered to the men who amused him, or who delighted the queen. A man could have his ears cropped for speaking out, his hand struck off for writing. Women could be strangled for witchcraft on the evidence of a village gossip. There are very great wrongs which can only be put right by a very real change. There has to be a parliament which is elected by the people. It has to sit by law, and not at the whim of the king. It has to protect the rights of the people and not those of the landlord. It has to protect the rights of the poorest, of the powerless. I had nothing against the king himself – except that he was untrustworthy both in power and out of it – but I have everything in the world against a king who rules alone.”

“Are you a Leveler?”

Lambert smiled. “Certainly these are Leveler beliefs, yes. And I’m proud to call Levelers my comrades. They are some of the staunchest and truest men under my command. Yet I am a man of property too; and I want to keep my property. I don’t go as far as some of them who want everything to be held in common. But to seek justice and the chance to choose your own government – yes, that makes me a Leveler, I suppose.”

“There has to be a leader,” Johnnie said stubbornly. “Appointed by God.”

Lambert shook his head. “There has to be a commander, just like in the army. But we don’t believe that God appoints a man to tell us what to do. If that were so, we might as well still obey the Pope and have done with it. We know what to do, we know what is right, we know that the hardworking men of this country need to be sure that their lands are safe, and that their landlord will not sell them to another, like a herd of cow, or suddenly take it into his head that their village is in his way and drive them out like coneys from a warren.”

Johnnie hesitated.

“When you marched to Colchester were you quartered on poor farms with nothing to spare?” Lambert asked.

“Yes.”

“Then you’ve seen how badly some men live in the middle of plenty. The rents they have to pay are greater than the yield of their crops. We cannot have people forever struggling to make that gap meet. There has to be a balance. People must be paid a fair wage for their work.” He paused. “When you were quartered on a poor farmstead did you take your feed for your horses and a chicken for your dinner and leave them no recompense?”

Johnnie flushed scarlet and shamefacedly nodded.

“Aye, that’s the royal way,” Lambert said bitterly. “That’s the kingly way to behave.”

Johnnie flushed. “I didn’t want to,” he said. “But I had no wages.”

Lambert gripped his arm. “That’s how it happens,” he said. “If all the wealth is concentrated on the king, on the court, then there must be poverty everywhere else. The king raised an army but had no funds so he didn’t pay you, so you had to take forage without paying, so at the end of the line there is some poor widow with one hen and the king’s man comes by and takes all the eggs.”

Hester watched her stepson and Lambert walk to the end of the orchard and then turn toward the lake.

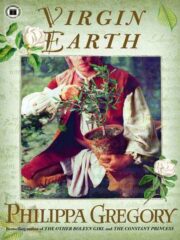

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.