The three of them were at dinner when there was a knock at the door. Hester turned her head and they listened to the cook stamping irritably along the hall to open it. There was the noise of a mild disagreement. “It’ll be a sailor with something to sell,” Hester said.

“I’ll go,” Johnnie said, pushing back his chair. “You finish your dinner.”

“Call me before you agree a price,” John warned him.

Johnnie scowled at his father’s lack of trust; and went out of the door.

They heard him shout an oath, and then they heard the noise of his running footsteps down the hall, and the door to the terrace slam as he set off down the garden.

“Good God, what now?” John sprang to his feet and went to the front door. Hester paused by the window to see Johnnie, head down, running blindly toward the lake. She hesitated, and followed her husband.

A bewildered man was at the front door. “I offered him this for sale,” he said, showing a dirty piece of black cloth. “I thought it was the sort of thing you would like for your collection. But he jumped back as if it were poison and fled from me. What ails the lad?”

“He’s sick,” Hester said shortly. “What is it?”

The man suddenly gleamed with enthusiasm. “A piece of pall from the scaffolding of the Martyr King, Mrs. Tradescant. And if you like it you can have it and a penknife cast from the metal of his statue. And I may be able to find you a scrape of earth soaked with his sacred blood. All very reasonable considering the rarity of it and the price you will be able to charge for those coming to see it.”

Hester instinctively recoiled in distaste. She looked to John. His eyebrows were knotted in thought.

“We don’t take such things,” he said slowly. “We buy rarities, not relics.”

“You have Henry VIII’s hunting gloves,” the man pointed out. “And Queen Anne’s nightgown. Why not this? Especially as you could make your fortune with it.”

John took a swift turn away from the doorstep and down the hall. The man was right, anything to do with the king would be a goldmine for the Ark, and they were barely making enough money to pay the cook’s and Joseph’s wages.

He turned back to the front door. “I thank you, but no. We will not exhibit the king’s remains.”

Hester found that her shoulders had been hunched while she waited for her husband’s decision. “But please do bring us any other rare things you have,” she said pleasantly, and went to shut the door.

The man thrust his foot out and stopped the closing door. “I was certain you would give me a good price for this,” he said. “There are other collectors who would pay handsomely. I was doing you the favor of coming to you first.”

“I thank you for that,” John said shortly. “But we won’t take anything that remains of the king.” He hesitated. “He visited here himself,” he said, as if it would make the decision clear. “It would not seem right to show pieces of him.”

The man shrugged, took his foot from the door and left. Hester closed the door and turned back to look at John.

“That was well done,” she said.

“D’you think we’d ever have got Johnnie to work in the room with the king’s own blood in a jar?” John asked irritably and went out to the garden, leaving his dinner untouched on the table.

Johnnie’s gloom did not lift as Hester had hoped it might even when the warmer weather came. In March, when John was planting seeds of nasturtium, sweet pea and his Virginian amaracock in pots of sieved earth in the orangery, Parliament declared that there would never more be a king or a queen set over the English people. Kingship was abolished forever in England. Johnnie came into the warm room with a small box in his hand, looking grave.

“What have you there?” John asked warily.

“The king’s seeds,” Johnnie said softly. “That he gave you to plant at Wimbledon.”

“Ah, the melon seeds. D’you know, I’d forgotten all about them.”

A swift, burning glance from Johnnie showed that he had not forgotten, and that he thought the less of his father for his absence of mind. “It’s one of the last orders he must have given,” Johnnie said softly, in awe. “And he sent for you by name, just to ask you to plant them for him. It’s like he wanted you to have a task, a quest, to remember him by.”

“Just melons.”

“He sent for you, he saved the seeds from his own dinner plate, and asked you to do it. He took the seeds from his own dinner, and he gave them to you.”

John hesitated, dismayed at the tone of worship in Johnnie’s voice. The skepticism which everyone in the country had shared when Charles the Cheat was lying and backsliding from his agreements had quite vanished at the man’s death when he became Charles the Martyr. John granted grudgingly that Charles had done better than anyone could have imagined in making the throne once more a sacred place; for here was Johnnie, who by rights should be disillusioned after a hopeless siege and a bad injury, with his eyes blazing at the thought of the dead king.

John put his hand on his son’s shoulder and felt the strong sinew and bone. He did not see how he could explain to Johnnie that the whim of a man accustomed all his life to command should not be read as significant. Charles the Last had a fancy to pretend that he might live to eat the melons which would be planted at Wimbledon in the spring, and it was no trouble to him that a servant should go all the way from Windsor to Lambeth and back again to fetch John, and that John should go all the way from Lambeth to Windsor and then home again to enact that fancy.

It would never have occurred to him that it might be inconvenient for a man no longer in his service and no longer paid a royal wage to be summoned once more to unpaid work. It would not have occurred to him that his behavior was arrogant or willful. It would not have occurred to him that by naming John as his gardener and entrusting him with the commission he would identify him as a royal servant at a time when royal servants were regarded with suspicion. He had put John to inconvenience, he might have put him in grave danger – he would simply never have thought of it. It was a whim and he was always a man who was happy that others should service his whims.

“Would you like to plant them?” John asked, seeking a way out of this dilemma.

Johnnie’s face showed the rush of his emotion. “Would you let me?”

“Of course. You can plant them up, if you like, and when they are ready we’ll transplant them to the melon beds.”

“I want to make melon beds at Wimbledon,” Johnnie said. “That’s where he wanted them to be.”

John hesitated. “I don’t know what’s happening at Wimbledon,” he said. “If Parliament wants me to continue working there, then of course we can make a melon bed. But I’ve heard nothing. They may sell the house.”

“We have to do it,” Johnnie said simply. “We cannot disobey his command, it was his last order to us.”

John turned back to his nasturtiums and surrendered. “Oh, very well,” he said. “When they’re ready for planting out we’ll take them to Wimbledon.”

Slowly, life began to get back to normal. There was a gradual increase of takings at the door from visitors to the rarities room and orders in the book from the new men who now found themselves in possession of the sequestered estates of royalists who were dead or fled or living quietly in poverty. The new men, officers from Cromwell’s army and the astute politicians who had stood against the king at the right time, walked into some fine houses and gardens running to seed which might be restored to beauty.

One by one the visitors started to come back to the Ark, to walk around the gardens and admire the blossoms on the trees and the bobbing heads of the daffodils. Dr. Thomas Wharton, a man after John’s heart, came to look at the rarities and brought with him a proposal that John should set aside a part of his garden for the College of Physicians. They would pay him a fee to grow herbs and medicinal plants for them.

“I appreciate it,” John said frankly. “These have been lean years for us. A country at war has no interest in gardening nor in rarities.”

“The country is to be run now by men whose curiosity will not be stifled,” the doctor replied. “Mr. Cromwell himself is a man who likes ingenious mechanisms. He has drained his farmland and uses Dutch windpumps to keep the water out, and he believes that English land could be made to yield as fruitfully as the Low Countries’, even the waste grounds.”

“It’s a question of not exhausting the soil,” John said eagerly. “And changing the crops around so that blights don’t take hold. We’ve always known that in gardens and vegetable plots, every convent and monastery garden moved crops from one bed to another each year, but it’s true for farmland too. It’s how to restore the goodness to the soil that is the difficulty. In Virginia too, the People never use the same field for more than three seasons.”

“The planters?”

“No, the Powhatan. They move their fields each season. I thought it was a mistake till I saw how their crops yielded.”

“This is most interesting,” Dr. Wharton said. “Perhaps you would come to my house and tell me more. I meet with friends once a month to discuss inventions, and rarities, and ideas.”

“I should be honored,” John said.

“And what d’you use to make your own land fertile?” Dr. Wharton asked.

John laughed. “A soup of my father’s devising,” he said. “Nettles and comfrey and dung stirred up in an evil pot. And if I am disposed to make water I piss in it as well.”

The doctor chuckled. “So it couldn’t be used for a hundred acres?”

“But there are crops which would put the goodness back into the soil,” John replied. “Comfrey or clover. You’d have to start with a little patch and harvest the seed, plant a greater and greater field every year.”

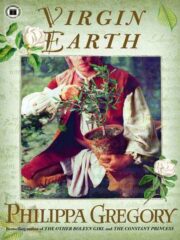

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.