“Oh God, don’t let him botch it,” John whispered, thinking not of the executioner who had done this a hundred times, but of the king who must do this beautifully, just once.

The king turned to Bishop Juxon and the bishop helped him to tuck his long hair under his cap to keep his neck free for the blade. Charles handed his George and the ribbon of the Garter to the bishop, and pulled the ring from his finger.

“No, not that, no, no,” John muttered. The details were unbearable. John had nerved himself for an execution; not for a man undressing as if in domestic confidence, tucking his hair out of the way of his pale, fragile neck. “Oh please God, no.”

Charles took off his doublet but wrapped his cloak around his shoulders again, as if it mattered that he should not catch cold. He seemed to be complaining about the executioner’s block. The executioner, a terrifying figure in his masquing disguise, seemed to be apologizing. John, remembering the king’s ability to delay and prevaricate, found that he was shaking the fence post before him in painful impatience.

The king stepped back and looked up at the sky, his hands raised. John heard the scribble of a pencil behind him as a sketch-maker captured the image of the king, the martyr of the people, his eyes on heaven, his arms outspread like a statue of Christ. Then the king dropped his cloak, knelt down before the block and stretched out his neck.

The executioner had to wait for the signal; the king had to spread out his arms to consent. For a while he knelt there, unmoving. The executioner leaned forward and moved a wisp of hair. He waited.

“Please, do it,” John whispered to his old master. “Please, please, just do it.”

There was a wait of what seemed like hours, then with the gesture of a man diving into a deep river the king flung his arms out wide and the ax swept a lovely unstoppable arc downward, thudded into his neck bone, and his head dropped neatly off.

A deep groan came from the crowd – the sound a man makes at his death, the sound a man makes at the height of his pleasure. The sound of something ending, which can never happen again.

At once there were slow, determined hoofbeats behind them and people screaming and pushing in panic to get away.

“Come on!” Alexander cried, tugging at John’s sleeve. “The cavalry is coming through, out of the way, man, we’ll be ridden down.”

John could not hear him. He was still staring at the stage, still waiting for the final act when the king, gorgeously dressed in white, would step down from the stage and dance with the queen.

“Come on!” Alexander said. He grabbed John’s arm and dragged him to one side. The crowd eddied, rushing to the sides of the street, many running forward to the scaffold to snatch a piece of the pall, to scrabble for a bit of earth from under the stage, even to dip their handkerchiefs in the gush of scarlet hot blood. John, pulled by Alexander, and pushed by the people behind him trying to get away from the remorseless cavalry advance down the street, lost his feet and fell. He was kicked in the head at once, someone trod on his hand. Alexander hauled him upward.

“Come on, man!” he said. “This is no place to linger.”

John’s head cleared, he struggled to his feet, ran with Alexander to the side of the road, pressed against the wall as the cavalry forced their way down to the scaffold, and then slipped away as they went past. At the top of the road he checked, and looked back. It was over. Already it was over. Bishop Juxon had disappeared, the king’s body had been lifted through the window of the Banqueting House, the street was half-cleared of people, the soldiers had made a cordon around the stage. It was a derelict theater at the end of the show, it had that stale leftover silence when the speeches have been finished and the performance is all over. It was done.

It was done but it was not over. John, returning home, found his house besieged with neighbors who wanted to hear every word, every detail, of what he had seen and what had been said. Only Johnnie was missing.

“Where is he?” John asked Hester.

“In the garden, in his boat on the lake,” she said shortly. “We heard the church bells toll in Lambeth and he knew what it was for.”

John nodded, excused himself from the village gossips and went down the cold garden. His son was nowhere to be seen. John walked down the avenue and turned right at the bottom for the lake where the children had often gone to feed ducks when they were little. The irises and reeds planted in the wet ground at the margin were in their stark frosted beauty. In the middle of the lake the boat was drifting, Johnnie, wrapped in his cape, sitting in the stern, the oars resting on the seat either side of him.

“Hey there,” John said gently from the landing stage.

Johnnie glanced up and saw his father. “Did you see it done?” he asked flatly.

“Aye.”

“Was it done quickly?”

“It was done properly,” John said. “He made a speech, he put his head on the block, he gave the sign and it was done in a single blow.”

“So it’s over,” Johnnie said. “I’ll never serve him.”

“It’s over,” John said. “Come ashore, Johnnie, there will be other masters and other gardens. In a few weeks people will have something else to talk about. You won’t have to hear about it. Come in, Johnnie.”

Spring 1649

John was wrong. The king’s execution was not a nine-day wonder, it swiftly became the theme of every conversation, of every ballad, of every prayer. Within days they were bringing to John the rushed printed accounts of the trial and eyewitness descriptions of the execution, and asking him if they were the truth. Only the most hard-hearted of round-heads escaped the mood of haunting melancholy, as if the death of a royal was a personal loss – whatever the character of the man, whatever the reason for his death. The country was gripped with a sickness of grief, a deep sadness which quite obscured the justice of the case and the reasons for his death. No one really cared why the king had to die. In the end, they were stunned that he had died at all.

John thought that perhaps others had believed like him: that a king in his health simply could not die. That something would intervene, that God himself must prevent such an act. That even now, time might run backward and the king be found alive. That John might wake up one morning to find the king in his palace and the queen demanding some absurd planting scheme. It was almost impossible to accept that no one would ever see him again. The chapbooks, the balladeers, the portraitists all fostered the illusion of the king’s surviving presence. There were more pictures of King Charles and stories about him than there had ever been during his life. He was better beloved than he had ever been when he had been idle and foolish and misjudging. Every error he had made had been washed away by the simple fact of his death, and the name he had given to himself: the Martyr King.

Then came the reports of miracles worked by his relics. People were cured of fits or sickness or rashes like the pox by the touch of a handkerchief that had been dipped in his blood. The pocketknives made from his melted-down statue would heal wounds if laid against them, would protect a baby from violent death if used to cut the cord. A sick lion in the Tower zoo had been comforted by the scent of his blood on a rag. Every day there was a new story about the saint, the people’s saint. Every day his presence in the country grew stronger.

No one was wholly unmoved; but Johnnie, still weak from his injury and defeat at Colchester, was struck very hard. He spent day after day in the boat on the little lake, lying wrapped in his cloak, his long legs folded over the stern and the heels of his boots dipping in the water while the boat drifted around nudging one bank and then another, and Johnnie stared up at the cold sky, saying nothing.

Hester went down to fetch him for his midday dinner and found him rowing slowly to the little landing stage to come in.

“Oh Johnnie,” she said. “You have your whole life before you, there’s no need to take it so hard. You did what you could, you kept faith with him, you ran away to serve him and you were as brave as any of his cavaliers.”

He looked at her with his dark Tradescant eyes and she saw the passionate loyalty of his grandfather without the security of his grandfather’s settled world. “I don’t know how we can live without a king,” he said simply. “It’s not just him. It’s the place he held. I can’t believe that we won’t see him again. His palaces are still there, his gardens. I can’t believe that he is not there too.”

“You should get back to work,” Hester said, grasping at straws. “Your father needs help.”

“We are gardeners to the king,” Johnnie said simply. “What do we do now?”

“There’s the trading business for Sir Henry in Barbados.”

He shook his head. “I’ll never be a trader. I’m a gardener through and through. I’d never be anything else.”

“The rarities.”

“I’ll come and help if you wish it, Mother,” he said obediently. “But they’re not the same, are they? Since we packed and unpacked them again. It’s not grandfather’s room anymore, it’s not the room we showed the king. We have most of the things and it should be the same. But it feels different, doesn’t it? As if by packing them and hiding them away, and then unpacking them, and then hiding them again, somehow spoiled it. And people don’t come as they used to. It’s as if everything is changed and no one knows yet how.”

Hester put her hand on his arm. “I just mean you should stop brooding and return to work. There is a time to mourn and you do yourself no favors if you exceed it.”

He nodded. “I will,” he promised. “If you wish it.” He hesitated as if he could not find the words for his feeling. “I never thought that I could feel so low.”

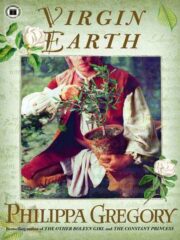

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.