“Why does he do it?” Alexander demanded.

John shook his head. “I doubt any man has ever turned his back to him before,” he said quietly. “He cannot learn to be treated as a mere mortal. He was brought up as the son of God’s anointed. He just can’t understand the depth of his fall.”

John Cook ostentatiously pulled his jacket into shape, and completely ignored the blow. He approached the judges’ table, and asked them to agree that if the king would not plead then his silence would be taken as a confession of guilt.

The king replied. John noticed that in this crisis of his life he had lost his stammer. His diffidence in speaking directly to people had gone at last. He was clear and powerful as he told the court, in a voice raised loud enough to ensure that he could be heard in the courtroom and by the men scribbling down every word, that he was defending his own rights, but also the rights of the people of England. “If a power without law can make laws, then who can be sure of his life or anything that he calls his own?”

There was a soft mutter from the courtroom, and a few heads nodded in the galleries where the men of property were especially sensitive to the threat that a parliament free of king and tradition might make laws that did not suit the men of land and fortune. There were Levelers enough to frighten the men of property back onto the side of monarchy. Those who called for the king’s execution today might call for park walls to be pulled down tomorrow, for a law which treated commoners and peers equally, and for a parliament which represented the workingman.

The Lord President Bradshaw, his metaled hat still clamped on his head, ordered the king to be silent, but Charles argued with him. Bradshaw ordered the clerk to call the prisoner to answer the charge but the king would not be silent.

“Remove the prisoner!” Bradshaw shouted.

“I do require-”

“It is not for prisoners to require-”

“Sir. I am not an ordinary prisoner.”

The guards surrounded him. “God no!” muttered John. “Don’t let them jostle him.”

For a moment he was back in the Whitehall palace courtyard with the king in the coach and the queen with her box of jewels. He had thought then that if one hand had touched the coach the whole mystery of majesty would be destroyed. He thought now that if one soldier took the butt end of his pike and irritably thumped Charles Stuart, then the king would go down, and all his principles fall with him.

“Sir,” the king raised his voice, “I never took arms against the people, but for the laws-”

“Justice!” the soldiers shouted. Charles rose from his chair, looked as if he wanted to say more.

“Just go,” John pleaded, his hands clapped over his mouth to prevent the words from being heard. “Go before some fool loses patience. Or before Cook pokes you back.”

The king turned and left the hall. Alexander looked at John.

“A muddled business,” he said.

“A miserable one,” John replied.

Tuesday, 23 January 1649

The hall doors did not open until midday. John and Alexander were chilled and bored by the time they pushed their way in. At once John’s eyes were taken by a great shield, white with the red cross of St. George, hung above the commissioners’ table, which was draped in a richly colored Turkey rug.

“What does it mean?” he asked Alexander. “Will they sentence him without another word?”

“If they decide that his silence means guilt then he cannot speak,” Alexander said. “Once sentence is pronounced he’ll just be taken out. That’s how all the courts work. There’s nothing more to say.”

John nodded in silence, his face dark.

There was a sympathetic murmur as the guards brought the king into court. John could see traces of strain in his face, especially around his dark, solemn eyes. But he looked at the commissioners as if he despised them and he dropped into his chair as if it were his convenience to be seated before them.

John Bradshaw, the man with the hardest task in England, pulled the brim of his hat down to his eyebrows and looked at the king as if he were not far off begging him to see reason. He spoke quietly, reminding the king that the court was asking him, once more, to answer the charges.

The king looked up from turning a ring on his finger. “When I was here yesterday I was interrupted,” he said sulkily.

“You can make the best defense you can,” Bradshaw promised him. “But only after you have given a positive answer to the charges.”

It was opening a door for the king; at once he soared into grandeur. “For the charges I care not a rush…” he started.

“Just plead not guilty,” John whispered to himself. “Just deny tyranny and treason.”

He could have shouted his advice out loud, nothing would have stopped the king. Bradshaw himself tried to interrupt.

“By your favor you ought not to interrupt me. How I came here I know not; there’s no law to make your king your prisoner.”

“But-” Bradshaw started.

The king’s outflung hand meant that Bradshaw should be silenced. The Lord President of the court tried again against the king’s torrent of speech. He gave up and nodded to the clerk of the court to read the charge.

John looked over to where Cromwell was sitting, his chin in his hands, watching the king dominating his own trial, his face grim.

The clerk read the long, wordy charge again. John heard his voice tremble at the embarrassment of being forced to read over and over again to a man who ignored him.

“You are before a court of justice,” Bradshaw asserted.

“I see I am before a power,” the king said provocatively. He rose to his feet and made that little gesture with his hand again which was a cue for a servant to bow and go. John recognized it at once but did not think that any other man in the court would realize that they had been dismissed. The king did not care to stay any longer.

“Answer the charges,” John whispered soundlessly as the guards closed around him and the king walked from the court.

Wednesday, 24 January 1649

John spent Wednesday idling at the little house in the Minories with Frances. The court was not sitting.

“What are they doing then?” Frances asked. She was kneading dough at the kitchen table, John seated on a stool at a safe distance from the spreading circle of flour. Frances had learned her domestic skills from Hester, so she would always be a competent cook; but her style was more enthusiastic than accurate and Alexander occasionally had to send out for their dinner after a catastrophe in the bread oven or a burned-out pot.

“They’re hearing witnesses,” John said. “It’s to put the gloss of legality on it. Everyone knows he raised the standard at Nottingham. We hardly need witness accounts on oath.”

“They won’t call you?” she asked.

He shook his head. “They’re seeking the smallest of trifles. They’re calling the man who painted the standard pole. And for the battles they’re using the evidence of men who fought all the way through. I was there only at the very beginning, remember. I was there at Hull which everyone has forgotten now. I never saw proper fighting.”

“Are you sorry now?” she asked, with her stepmother’s directness. “Do you wish you had stayed by him?”

John shook his head. “I hate to see it come to this, but it was a bad road wherever it led,” he said honestly. “We would be in a far worse case today if he had succeeded, Frances. I do know that.”

“Because of the Papists?” she asked.

John hesitated. “Yes, I do think so. If he is not a Papist himself then the queen certainly is and half the court with her. The children – almost bound to be. So Prince Charles may be, and then his son after him, and then the door open again to the Pope and the priests and the monasteries and the convents and the whole burden of a faith that is ordered on you by your masters.”

“But you don’t even pray,” she reminded him.

John grinned. “Yes. And I like to not pray in my own way. I don’t want to not pray in a Papist way.” He broke off at her chuckle. “I have traveled too far and seen too much to believe in anything very readily. You know that. I have lived with people who prayed very faithfully to the Great Hare and I prayed alongside them and sometimes thought my prayers were answered. I can’t see only one way anymore. I always see a dozen ways.” He sighed. “It makes me uncomfortable with myself, it makes me a poor husband and father, and God knows it makes me a poor Christian and bad servant.”

Frances paused in her work and looked at him with love. “I don’t think you’re a bad father,” she said. “It’s as you say – you have seen too much to have one simple view and one simple belief. Nobody could have lived as you did, so far from your own people, and not come home feeling a little uneasy.”

“My father traveled farther and saw stranger sights but he loved his masters till the day of his death,” John said. “I never saw him have a single doubt.”

She shook her head. “Those were different times,” she said He went far as a traveler. But you lived with the people in Virginia. You ate their bread. Of course you see two ways to live. You have lived two ways. And in this country everything changed the moment the king took up arms against his people. Before then there were no choices to be made. Now you, and many others, see a dozen ways because there are a dozen ways. Your father had only one way: and that was to follow his master. Now you could follow the king, or follow Cromwell, or follow Parliament, or follow the army, or become a Leveler and call for a new earth for us all, or a Clubman and fight only to defend your own village, or turn your back on them all and emigrate, or shut the door of your garden and have nothing more to do with any of them.”

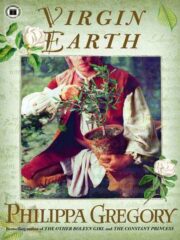

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.