Johnnie flushed and moved uneasily in his chair. “How can he? How can he agree to become nothing? He’s the king in the sight of God. Does he call God a liar?”

Frances crossed to him and took his hand. “Now you stop,” she said with the firmness of an older sister. “You’ve done your fighting for him. You’ve done quite enough, and it did no good for anybody. The king must take his own decision, it’s nothing to do with you now, or any of us.”

“She’s right,” Hester said. “And none of us can do anything for or against the king. He has traveled his own road. He will have to decide what he should do now.”

The king decided to take the high road of principle – or perhaps he decided he would gamble once again – or perhaps he decided he would make a gesture, a proud theatrical gesture, and see what came of it. He rejected Parliament’s proposals boldly, recklessly, outright. And then he waited to see what would happen next.

What happened next rather surprised him. The men of Cromwell’s army, Lambert’s men, Fairfax’s men, furious at the delays and missed opportunities, clear in their own minds that what should happen next was an unbreakable peace and a reform of the laws of the land in favor of hardworking common people, invaded the House of Commons, excluded those Members of Parliament known to be sympathetic to the king, and insisted that the king should be brought to trial for treason against his subjects.

Hester brought the news to John as he was watering the tender plants in the orangery. The frost on the windowpane was melting and the glass was dewy and opaque. The citrus trees, their boughs carrying the last glowing fruit of oranges and lemon, scented the room, the charcoal in the hearth shifted and crackled as it glowed. Hester paused on the threshold, reluctant to break the sense of peace. Then she set her lips and marched into the room.

“They have taken the king from the Isle of Wight and are bringing him to London. They have called him for trial,” she said flatly. “They have accused him of treason.”

John froze where he stood, the watering bottle dribbling cold water on his boot. “Treason?” he repeated. “How can a king be charged with treason?”

“They say he tried to steal away the people’s liberty and to set up a tyranny,” Hester said. “And to make war on his people is supposed to be treason.”

The water made a little puddle around John’s feet but he did not notice it, and neither did Hester, her gaze fixed on his stunned face.

“Where is he?” John asked numbly.

“On the road to London, that’s what they’re saying in Lambeth. I suppose they’ll put him in the Tower, or perhaps under arrest in one of the palaces.”

“And then?”

“They say that he is to be tried for treason. Before a court. A proper trial.”

“But the punishment for treason…”

“Is death,” Hester finished.

Just before Christmas there was a knock at the door. Johnnie, still nervous, started at the loud sound and Hester, hurrying to open it, whispered a blasphemy at whoever had disturbed her boy.

As she opened the door she composed her face into stern serenity at the sight of the armed man.

“Message for John Tradescant, as was gardener to the king,” the man said.

“Not here,” Hester said with her habitual caution.

“I’ll leave the message with you then,” the man said cheerfully. “The king wants to see him. At Windsor.”

“He is summoned to Windsor by the king?” Hester asked, disbelievingly.

“As he likes,” the man said disrespectfully. “The king orders him there, he can go or no as he likes as far as I’m concerned. I take my orders from Colonel Harrison, who guards the king. And his orders were to tell Mr. Tradescant that the king is asking for him. And now I’ve done that. And now I’m off.”

He gave her a friendly nod and crossed the little bridge to the road before Hester could say another word. She watched him march up the road to the ferry at Lambeth before she closed the door and went to find John in the garden.

He was pruning the roses with a sharp knife, his hands a mass of scratches from his work.

“Why won’t you wear gloves?” Hester remarked irritably.

He grinned. “I always mean to, then I start work and I think I can do it without scratching myself, and then I can’t be troubled to stop and go and find them, and then I draw blood and think there’s no point in fetching them now.”

“You’ll never guess who came to the door.”

“All right. I never will.”

“A messenger from the king,” she said, watching for his reaction.

He stiffened, like an old hunter when it hears the hunting horn. “The king sent for me?”

She nodded. “To attend him at Windsor. The man was clear that you need not go unless you wish. The king has no power to order you to obey. But he brought the message.”

John stepped carefully through the rosebushes, disentangling his coat when it was caught by a thorn, his mind already at Windsor.

“What can he want of me?”

She shrugged. “Not some harebrained scheme of escape?”

He shook his head. “Surely not. But there’s nothing to interest him in the garden at this time of year.”

“Will you go?”

Already he was walking toward the house, his pruning knife slipped in his belt, his roses almost forgotten. “Of course I have to go,” he said.

They had no horse, there was not enough money to replace the mare who had carried Johnnie to Colchester and been slaughtered for meat during the siege. John walked to the ferry at Lambeth and took a boat upriver to Windsor.

The castle looked much the same: a guard of soldiers at the door, the usual bustle and work that surrounded the royal court. But it was all strangely diminished: quieter, with less excitement, as if even the kitchen maids no longer believed that they were cooking the meat of God’s own anointed representative on earth, but instead working in a kitchen for a mere mortal.

John paused before the crossed pikes of the men on guard.

“John Tradescant,” he said. “The king sent for me.”

The pikes were lifted. “He’s at his dinner,” one of the soldiers said.

John went through the gateway, through the inner court, and into the great hall.

There was an eerie sense of a life lived again. There was the royal canopy billowing a little in the drafts from the open windows. There was the king seated in state below it, the great chair before the great table, and the table crowded with dishes. There were the common people, crammed into the gallery, watching the king eat as they always did. There was the yeoman usher to declare the table ready for laying, the yeoman of ewry to spread the cloth, the yeoman of pantry to lay out the long knives, spoons, salt and trenchers, the yeoman of cellar standing behind the chair with the decanter of wine. It was all as it had been, and yet it was completely different.

There was no constant ripple of laughter and wit, there was no vying for the eye of the king. There was no plump, ringleted queen at his side, and none of the glorious portraits and tapestries which had always been hung in his sight.

And Charles himself was changed. His face was scarred with disappointment, deep bags beneath his dark eyes, lines on his forehead, his hair thinner and streaked with gray, his mustache and beard still perfectly combed, but paler with white hairs where it had been glossy brown.

He looked down the hall and saw John; but his habitual diffidence did not allow him to greet a friendly face. He merely nodded and with a tiny gesture indicated that John should wait.

John, who had dropped to his knee as he came into the hall, rose up and took a seat at a table.

“What you kneeling for?” a man asked critically.

John hesitated. “Habit, I suppose. Do you not kneel in his presence?”

“Why should I? He’s no more than a man, as I am.”

“Times are changing,” John observed.

“You eating?” another man said.

John looked around. These were not the elegant courtiers who used to dine in the hall. These were the soldiers of Cromwell’s army, unimpressed by the ritual. Hungry, honest, straightforward men at their dinner.

John drew a trencher toward him and took a spoonful of meat from the common bowl.

When the king had finished dining one yeoman came forward and offered him a bowl to wash his fingertips while another offered the fine linen cloth to dry his hands. Neither of them kneeled, John noticed, and wondered if the king would refuse their service.

He did not even complain. The king took the service as it would have been offered to a mere lord of the manor. He did not even remark that they were not on their knees. John saw the mystery of kingship shrink before his eyes.

John rose at his place, waiting for an order. The king crooked his finger and John approached the high table, paused and bowed.

King Charles rose from his seat, stepped down from the dais and snapped his fingers for a pageboy, who sprang to follow him.

“I d-dined on melons two nights ago,” he remarked to John as if no time at all had passed since John and the queen and the king had planned the planting of Oatlands together. “And I th-th-thought that we always said we should have a m-melon bed at Wimbledon. I saved you the seeds for p-planting.”

John bowed, his mind whirling. “Your Majesty?”

The pageboy stepped forward and handed John a little wooden box filled with seeds.

“W-will they grow at Wimbledon?” the king asked as he walked past John to his inner chamber.

“I should think so, Your Majesty,” John said. He waited for more.

“Good,” said the king. “Her M-Majesty will like that, when she s-sees it. When she comes h-h-home again.”

“And then he was gone,” John said to an astounded Hester and Johnnie, sitting at the fireside after a long, cold boat trip back to Lambeth.

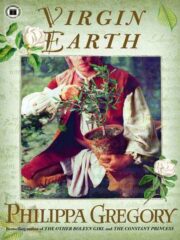

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.