The soldiers under Cromwell had forged their faith in themselves, in their cause and in their God during the long, hard years of fighting; they were not men who would now welcome a compromise. They wanted their pay; but they also wanted the country new-made. They had worked out their beliefs and philosophy in between battles, on forced marches, on dark nights when the rain doused their campfires. They had given up four years of peaceful life at home to fight for the causes of religious and political freedom. They wanted to see a new world in return for their sacrifice. They were under the command of Thomas Fairfax and John Lambert, two great generals who understood them and shared their beliefs, and marched them on the faithless, fearful city of London to ensure that Parliament did not bow to pressure and make a peace with a king who should be deep in despair and not radiant with hope.

Frances took her husband’s note to her father, who was hoeing the new vegetable bed. He looked at it briefly, and handed it back to her.

“You’ll stay here,” he said.

“If I may.”

He tipped his hat over his eyes and grinned at his daughter. “I imagine we can endure your company. Will you keep an eye on Johnnie for me? I don’t want him marching up to Parliament with a pruning hook over his shoulder, thinking he is bringing the king home to his own.”

“Mother is more afraid that it’ll be you running off to enlist.”

John shook his head. “I’ll not take up arms ever again,” he said. “It’s not a trade I do well. And the king is not a captivating master.”

Alexander wrote almost daily, reporting the fluctuations in the mood of the city. But it was all resolved in August when the army, under the command of General John Lambert, marched into London and declared that they could and would make peace with the king. With the House of Lords they drew up proposals to which any king could agree. Cromwell himself took the proposals to King Charles at Hampton Court.

“He will agree to them and be restored,” Alexander Norman said over a comfortable bottle of wine on the terrace. Frances sat on a stool at her husband’s feet and he rested his hand on her golden-brown head. Hester sat opposite John, who was in his father’s chair – facing out over the garden, watching the fruit in the orchard gilded with the last rays of sunshine. Johnnie sat at the top of the terrace steps. At Alexander’s words he gave a radiant smile.

“The king will be returned to his palaces,” he said wonderingly.

“Please God,” said John. “Please God that the king sees where his interests lie. He told me that he would set the army against Parliament and conquer them both.”

“Not with John Lambert in command,” Hester remarked. “That man is not a fool.”

“Can it all be as it was?” Frances asked. “The queen come home, and the court restored?”

“There’ll be some missing faces,” Alexander pointed out. “Archbishop Laud for one, Earl Strafford.”

“So what was it all for?” Hester asked. “All these years of hardship?”

John shook his head. “In the end, perhaps it was to bring the king and Parliament to realize that they have to deal together, they cannot be enemies.”

“A high price to pay,” Frances said, thinking of the years when she and Hester had struggled on their own at the Ark, “to get some sense into that thick royal head.”

Autumn 1647

“He’s gone,” Alexander said flatly the moment he entered the kitchen door and surprised the Tradescants at breakfast. His horse stood sweating in the stable yard outside. “I came at once to tell you. I rode over. I couldn’t bear to wait. I couldn’t believe it myself.”

“The king?” John leaped to his feet and strode to the door, checked and turned back.

Alexander nodded. “Escaped from Hampton Court.”

“Hurrah!” Johnnie shouted.

“My God, no,” John said. “Not to the French? Not when they were so near agreement? The French haven’t rescued him? Kidnapped him?”

Alexander shook his head and dropped into John’s vacated seat. Frances put a mug of small ale beside him and he caught her hand and kissed the inside of her wrist in thanks. “I heard the news this morning and came straight here with it. I couldn’t bear even to write it. What days we live in! When will we ever see an end to these alarms!”

“When will we ever see peace?” Hester murmured, one eye on her husband who was standing at the window gazing out into the yard as if ready to run himself.

“Who’s got him?” John demanded. “Not the Irish?”

“He just slipped away on his own, by the looks of it. There’s not word of him being broken out by soldiers. Just away with his gentlemen.”

“Sir John Berkeley,” John guessed.

Alexander shrugged. “Maybe.”

“And where has he gone? France? To be with the queen and Prince Charles?”

“If he has any sense,” Alexander said. “But why break away now? When things were going so well? When they were so close to agreeing to what he wanted? When he had an agreement with the army that he could sign? All he had to do was wait. The City is for him, Parliament is for him, the army has nothing but fair demands, Cromwell has destroyed the opposition. He has nearly won.”

“Because he always thinks he can do better,” John exclaimed despairingly. “He always thinks he can do a little more by a grand gesture, a great chance. My father saw him ride out to Spain with the Duke of Buckingham when he was a young prince, and wild and reckless. He never learned the line between taking a risk and ripe folly. No one ever taught him to take care. He likes the masque – the style and the action. He’s never seen that it is all pretend. That real life isn’t like that.”

Hester sank back in her chair and glanced down the table at her stepson. Johnnie was looking mutinous. She put out a hand to warn him to hold his silence, but the boy burst out:

“It’s the greatest of things! Don’t you see? He’ll be safe in France by now, and they can beg his pardon from there! The queen will have an army ready for him to command, Prince Rupert will take the cavalry again. They said that he was defeated but he was not!”

John turned a dark look on his son. “You’re right about only one thing,” he said somberly. “He’s never defeated.”

“That’s the wonderful thing about him!”

John shook his head. “It’s the worst.”

Alexander stayed for breakfast and then agreed to stay on for the rest of the week. John was restless all day and at mid-afternoon he went to find Hester.

She was in the rarities room, bringing the planting records up to date in the big garden book.

“I can’t stay here, not knowing what’s going on,” John said briskly. “I’ll go into Whitehall, see if I can hear some news.”

She put down her pen and smiled at him. “I knew you’d have to go,” she said. “Make sure you come home, don’t be caught up in whatever is going on there.”

He paused in the doorway. “Thank you,” he said.

“Oh! For what?”

“For letting me go without badgering me with a dozen questions, without warning me a dozen times.”

She smiled but it did not reach her eyes. “Since you would go whether I give you leave or no, I might as well give you leave,” she said.

“That’s true enough!” John said lightly and went from the room.

Whitehall was in a frenzy of gossip and speculation. John went into a tavern where he might find an acquaintance, bought a mug of ale and looked around for a face he knew. At a nearby table were a group of Africa merchants.

“Mr. Hobhouse! Any news? I have come up from Lambeth especially and all I can get is what I know already.”

“You know that he’s gone to the Isle of Wight?”

John recoiled. “What?”

“Carisbrooke Castle. He’s set himself up in Carisbrooke Castle.”

“But why? Why would he?”

The merchant shrugged. “It’s not a bad plan. No one can trust the navy, and if they declare for him how is Cromwell’s army going to lay hold of him? He could be snug enough at Carisbrooke, create his court, build his army, and when he is ready sail straight into Portsmouth. He must have had some secret arrangement with the governor Robert Hammond, though everyone thought that Hammond was a Parliament man through and through. The king must have had a deep plan. He’ll be waiting for the queen’s army from France and then we’ll be at war again, if anyone has the stomach for it.”

John briefly closed his eyes. “This is a nightmare.”

The merchant shook his head. “I cannot tell you how much money I am losing every day this goes on,” he said. “I can’t induce men to serve, my ships are harassed by pirates in the very mouth of the Thames, and I never know when a ship comes in what price I can command on the quayside or what taxes I shall have to pay. These are times for a madman. And we have a mad king to rule over us.”

“Not another war,” John said.

“He must have laid his plans very deep,” the merchant said. “He was promising to agree with Cromwell and Ireton only the day before, he gave his word as a king. He was about to sign. What a man! What a false man! Y’know, in business we’d never deal with him. How would I manage if I gave my word and then skipped away?”

“Deep-laid plans?” John asked, seizing on the one unlikely feature.

“So they say.”

One of the other merchants glanced up. “D’you know better, Mr. Tradescant? You were at Oatlands with him, weren’t you?”

John sensed the sudden intensity of interest. “I was planting the garden. He hardly spoke to me. I saw him walk by, nothing more.”

“Well, God save him and keep him from his enemies,” one of the men said stoutly and John noticed that while only a few months before the man would have been booed into silence or even thrown out of the tavern there were now a few men who muttered “Amen” into the bottom of their mugs, and no one who denied the wish.

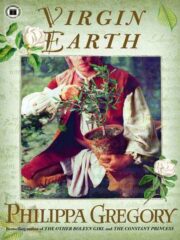

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.