Johnnie had brought up the pots from the riverside.

“Good lad,” John said with pleasure, glad of the chance to set about his work and restore normality at least to the flower beds. “Let’s take these up to the royal court. At least that can be looking right in a couple of days.”

They worked hard, side by side, and John enjoyed his son’s company. The boy had inherited the Tradescant gift with plants, he handled them as if he loved the touch of the silky white roots, the caress of damp earth. When he hefted a pot in his hand he could tell from the weight whether it needed watering. When he tipped a plant out into his palm he never knocked the blooms. When he set it into a hole and pressed down the earth there was something about his touch which was both precisely judged, and quite unknowing.

“You may be the greatest gardener of us all,” John said at the end of the second day as they walked homeward with their tools over their shoulders. “I don’t believe I had your way with plants when I was your age.”

Johnnie gleamed. “I love the plants. Not so much the rarities,” he said.

“Not the rarities?” John asked, amazed.

His son shook his head. “What I’d rather do, more than anything else, would be to collect new plants, to go with you to the Americas, the West Indies, travel, find things, bring them home and grow them. The rarities – well, they just sit there, don’t they? Once they’re in place there is nothing more to do with them except keep them dusted. But plants grow and blossom and fruit and seed and then there’s next year to plant them again. I like how they change.”

John nodded. “I see.”

He was about to remark that the rarities played their part in the Tradescant family fortune when he heard hoofbeats on the drive. “What’s that?” he asked.

“Could it be the king?”

“Could be.”

John turned and ran toward the silkworm house, cast down his tools, grabbed his coat and turned to run back to the palace. Johnnie danced on the spot. “Can I come? Can I come?”

“Yes. But remember what I said about keeping silent.”

Johnnie fell into line behind his father, mirrored his father’s long stride, composed his face to a scowl of what he hoped was dignified discretion, and spoiled the effect only slightly by a great bounce at every fourth step as his excitement proved too much for him.

They ran round to the stable yard and there, in the dirty stall, was the king’s Arab, and a dozen other horses of his escort.

“The king here?” John asked a trooper.

“Just arrived,” the man said, easing the girth of his horse. “We had to stop at every village for him to touch people.”

“Touch people?”

“They turned out in dozens,” the man said abruptly. “With all sorts of illnesses and sores and God knows what. And again and again he stopped and touched them, so that they would be cured. And they all went off, back to their hovels, back to their porridge of nothing and water, thinking that he had done them a great favor and that we were some kind of beast to imprison him.”

John nodded.

“Who are you?” the man asked. “If you want a favor of him, he’ll do it. He’s the most charming, generous, agreeable man to ever take a country into disaster and death and four years of war.”

“I’m the gardener,” John replied.

“Then you’ll see him,” the man said. “He went out to sit in the garden with his companions, while someone cooks his dinner, and sweeps his chamber, and makes everything ready for him so that he can dine in comfort and sleep in comfort. While I and my men do without.”

John turned on his heel and went round to the royal court.

The king was seated on a bench, his back against the warm brick wall, looking around him at the newly weeded, newly planted garden. Standing behind him were a couple of gentlemen that John did not know, another stranger strolled on the newly raked paths. When the king heard John’s footsteps he glanced up.

“Ah…” For a moment he could not remember the name. “Gardener Tradescant.”

John dropped to his knee and heard Johnnie behind him do the same.

“Your w-w-work?” the king asked with his slight stammer, gesturing to the dug-over beds.

John bowed. “When I heard you were coming to Oatlands I came to do what I could, Your Majesty. With my son: John Tradescant.”

The king nodded, his dark eyes half-lidded. “I thank you,” he said languidly. “When I am returned to my proper place I shall see that you are returned to yours.”

John bowed again and waited. When there was silence he glanced up. The king made a small gesture of dismissal with his hand. John rose to his feet, bowed and walked backward, Johnnie skipping nervously out of the way as his father suddenly reversed, and then quickly copying him. John bowed again at the gateway to the garden and then stepped backward till he was out of sight.

He turned and met Johnnie’s astounded face. “And that’s it?” Johnnie demanded. “After we came here without being asked, and worked without pay for all this time to make it lovely for him?”

John gave a little snort of amusement and started to walk back to the silkworm house. “What did you expect? A knighthood?”

“I thought-” Johnnie started and then broke off. “I suppose I thought he might have some task for us, or he might be glad of us, he might see that we were loyal and thank us-”

John snorted again and opened the little white wooden door. “This is not a king who has plans or gives thanks,” he said. “That’s one of the reasons he’s where he is.”

“But doesn’t he realize that you needn’t have come at all?”

John paused for a moment and looked down at the stricken face of his boy. “Oh Johnnie,” he said softly. “This is not the king of the broadsheet ballads and the church sermons. This is a foolish man who ran into the war because he would not take advice, and when he took advice at all, always chose the wrong people to guide him.

“I came today as much for my father as for the king. I came because my father would have wanted to know that when the king came to his palace, the gardens were weeded. It would have been a matter of duty for him. It was a matter of pride for me. If I had freely chosen my way I would have been for the rights of workingmen and against the king. But I could not choose freely. I was in his service, and there have been some days – most days – when even seeing him as a fool I pity him from the bottom of my heart. Because he is a fool who cannot help himself. He does not know how to be wise. And his folly has cost him everything he owned.”

“I thought he was a great man, like a hero,” Johnnie remarked.

“Just an ordinary man in an extraordinary place,” John said. “And too much of a fool to know that. He was taught from birth that he was half divine. And now he believes it. Poor foolish king.”

John and Johnnie stayed the month working at Oatlands. The cook that Parliament had sent with the king needed fresh vegetables and fruits from the kitchen garden and by picking and choosing from the overgrown beds the two Tradescants were able to send fresh food up to the house each day. The king was surrounded by a small court and his imprisonment seemed more like a guard of honor. He hunted, he shot at archery, he ordered John to roll the bowling green smooth so that they could play at bowls.

John was considering paying for some boys to help with the weeding and planting in winter greens, when the news came that the king was to be moved to Hampton Court. Within a few hours the horses were saddled and the retinue was ready to move on.

The king was in the garden, waiting to be told that his escort was ready. John found he could not keep away from the excitement of great events, and took his pruning hook to the climbers on the far wall of the royal court.

The king, strolling around with two of his courtiers, came upon John and paused to watch him work as the two men stood aside.

“I shall see you repaid for this,” he said simply. He smiled a sly little smile. “Sooner perhaps than you think.”

“John jumped from his ladder and dropped to one knee. “Your Majesty.”

“They may have defeated my army, but now they tear themselves apart,” the king said. “All I must do is wait, p-patiently wait, until they beg me to come to the throne and set all to rights.”

John risked an upward glance. “Really, Your Majesty?”

The king’s smile transformed him. “Y-Yes. Indeed. The army will destroy P-Parliament, and then t-tear themselves apart. Already the army tells P-Parliament what it should do. When they have no enemy they have no c-common cause. All they could do was to destroy, it needs a k-king to rebuild. I know th-them. There is L-Lambert. He heads the f-faction against Parliament. He will lead the army against P-Parliament and then I will have w-won.”

John paused before he could find the words to reply. “So Your Majesty will greet them kindly when they come? And make an agreement with them?”

The king laughed shortly. “I shall w-win the argument, though I lost the b-battle,” he said.

A trooper came to the garden gate. “We are ready to leave, Your Majesty,” he called.

King Charles, who had never before this year ever done another man’s bidding, turned and went from Tradescant’s garden.

John and his son went down to the gatehouse to see them leave. John was half expecting a summons to Hampton Court, but the king went by with only a flicker of recognition that his gardener was on his knees at the roadside.

“And that’s it?” Johnnie demanded again.

“That’s it,” John replied shortly. “Royal service. We’ll set things in order tomorrow and we’ll go home the next day. Our work here is done.”

They discovered why the king had been moved when they got home. The City was in uproar with the apprentices rioting in favor of the king’s return and the army had thought it safer to have him at Hampton Court with a larger garrison around him. Alexander Norman had sent Frances to the Ark for safety and forbidden her to return to the City until the riots were over – whether they were ended by the return of the king to his throne, the seizing of control by Parliament, or the arrival of Cromwell’s army. There were now three players in the game for England. The king, playing one side against the other and hoping; Parliament, increasingly directionless and fearful of its future; and the army, which seemed to be the only force with a vision of the future and the discipline and determination to make it happen.

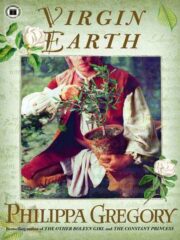

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.