John flashed her a quick, irritated look. “Papists and Scotsmen?” he asked. “Fighting for a Protestant king? An Irish army? The alliance would last half a day and the country would never forgive him.”

“If he is a Protestant king,” Hester said carefully.

John dropped his head into his hands. “No one knows what he believes anymore, nor what he stands for. How could it have come to this?”

“And what do you believe?” Hester asked him. “You were always against the court, and against Papacy?”

John shrugged wearily. “I didn’t go to Virginia just because I had no stomach for killing Englishmen,” he said. “I went because I was torn. I served the king, and my father served the king or his servants all his life. I can’t just turn away and pretend that I don’t care for his safety. I do care. But he’s in the wrong and has been in the wrong since-” He broke off. “Since he marched his soldiers into the House of Commons,” he said. “No, before. Since he allowed the government of this country to be run by that madman, Buckingham. Since he took a Papist wife and thus ran the risk of Papist children. From the moment that he set his heart on having a kingdom run as a tyranny and would not listen to his advisers.”

Hester waited.

“I want the kingdom free of his tyranny, I have always wanted that. But I don’t need the kingdom free of him. Or his son. Does that make any sense at all?”

Hester nodded and then turned to a more pressing topic for her. “Shall we unpack the rarities?”

John gave a short laugh. “D’you think we are at peace? With the king held by the Scots at Newcastle and refusing to agree with his own Parliament?”

“I don’t think we’re at peace,” she said equably. “But if we could show the rarities and summon people to the garden to see the Virginian plants we might make some money this summer. And we are in debt, John. This war has been hard on everyone and we are taking no more than a few shillings each month.”

He rose from the chair. “Let’s go and have a look at that tree,” he said.

They stood before the great black cherry tree. It had not liked the situation before the ice-house door, and there had been few blossoms in spring and now only a few buttons of green berries which might, in time, ripen and swell.

“I can’t bear to chop it down,” John said. “It has grown to a good size even if it is not bearing much of a crop.”

“Can you move it?” Hester asked. Her gaze went beyond the tree, to the doorway of the ice house where the ivy and the honeysuckle were planted. No one could have spotted its outline unless they were looking for it. She liked the thought of the garden plants helping to hide the rarities. There was some unity in the Ark if they all worked together to save the precious things.

“My father had a way of moving even big trees,” John said thoughtfully. “But it takes time. We’ll have to be patient. It will be a couple of months at the earliest.”

“Let’s do it,” Hester said. “I am ashamed of the rarities room as it is, I want the treasures back inside.” She did not tell John that while the king was held by the Scots she had no fears for the safety of the treasures or of the family. Hester had great faith in Scottish efficiency, and in the dour Covenanters’ immunity to Stuart charm. If the Scots were holding the king, even if they took him far away to Edinburgh, then Hester felt safe.

Hester remembered the moving of the cherry tree as an event which coincided with the death of the hopes of the runaway king. Both processes happened in slow stages. John dug a trench around his father’s cherry tree and watered it every morning and night. The news from Newcastle was that the king would agree to nothing: neither the proposals from England nor those from his hosts the Scots.

With the help of Joseph and Johnnie pulling the trunk slowly first one way and then the other, John dug underneath the tree and gently shoveled earth away from all but the greatest roots. A Scottish cleric who had wrestled with the king’s conscience for two months went home to Edinburgh and died, they said, of a broken heart, blaming himself that the most stubborn man in England could not be brought to see where his own interests lay.

John watered the tree richly with his father’s mixture of stinging-nettle soup, dung, and water, three times a day. They heard that the queen herself wrote to the king and begged him to make an agreement with the Scots, so that he might be king of Scotland at least.

John pruned the tree, carefully cutting away the branches which would sap the tree’s strength. The Scots Covenanters, debating with their royal prisoner, privately declared among themselves that he was mad, he must have been mad to come to them without an army, without power, without allies, and then imagine that they would fight a war for him, on his terms, against their co-religionists for nothing more than his thanks.

Johnnie and Joseph, with John and Alexander on the other side, gently thrust poles from one side of the crater around the tree to the other until it was supported, and then John went down into the mud-filled ditch and freed the last of the roots. The longest, strongest root he pulled gently from the mud and then cursed when it broke and he fell back into the slurry with a bump.

“That’s killed it,” Joseph said gloomily, and John climbed out of the ditch soaked through and irritable. Then the four men gently lifted the tree out of the ground and carried it down to the bottom of the orchard where a new hole was dug and waiting. They put it in, lovingly spread out the roots, backfilled the earth, and gently pressed it down. John stood back and admired his work.

“It’s crooked,” Frances said behind him.

John turned wrathfully on her.

“Just joking,” she said.

With the doorway clear, Hester tied a duster over her head to keep off the cobwebs and spiders and set to pulling aside the ivy and the honeysuckle. The key still worked in the lock, the door opened with a creak on the dirty hinges. John peered inside. The little round chamber was lined with straw and piled high with chests and boxes of his father’s treasures. He caught Hester’s dirty hand and kissed it. “Thank you for keeping them safe,” he said.

Autumn 1646

Hester, Johnnie and Joseph were lifting tulip bulbs in the garden of the Ark. They worked with their fingers in the cold soil. Even the common bulbs were too valuable to risk spearing with a fork or slicing with a spade. On the ground beside Hester were the precious porcelain bowls of the most valuable tulips, their expensive bulbs already lifted and separated, the sieved earth tipped back into the beds.

Joseph and Johnnie filled the labeled sacks with the Flame tulip bulbs. Almost every one had spawned a second, some of them had two or three bulblets nestling beside the first. All three gardeners were smiling in pleasure. Whether the price for tulips ever recovered or stayed as low as it had been thrust by the collapse of the market, still there was something rich and exciting about the wealth which made itself in silence and secrecy under the soil.

There was a step on the wooden floor of the terrace and Hester looked up to see John Lambert. He was looking very fine, dressed as well as always, with a deep violet feather in his hat, and a waterfall of white lace at his throat and cuffs. Hester got to her feet and felt a pang of annoyance at her dirty hands and disheveled hair. She whipped off her hessian apron and walked toward him.

“Forgive me coming unannounced,” he said, his dark smile taking in her rising blush. “I am so honored to see you working among your plants.”

“I’m all dirty,” Hester said, stepping back from his proffered hand.

“And I smell of horse,” he said cheerfully. “I am on my way from my home in Yorkshire. I couldn’t resist calling in to see if my tulips were ready.”

“They are.” Hester gestured to the three bulging sacks at the corner of the terrace. “I was going to send them to your London home.”

“I thought you might. That’s why I have come. I am on my way to Oxford and I wanted the special tulips there. I shall plant them in pots and have them in my rooms.”

Hester nodded. “I am sorry you will not meet my husband,” she said. “He is in London today. He has gone into trade in a small way with a West India planter and he is sending some goods out.”

“I am sorry not to meet him,” John Lambert said pleasantly. “But I hardly dare to delay. I am to be governor of Oxford while my health mends.”

Hester risked a quick glance at him. “I had heard you were ill – I was sorry.”

He gave her his warm, intimate smile. “I am well enough, and the work I set myself to do is all but done. Pray God we will have peace again, Mrs. Tradescant, and in the meantime I can sit down in Oxford and make sure that the colleges get back into some kind of order, and their treasures are safe.”

“These are hard times to be a guardian of beautiful things.”

“Better times coming soon,” he whispered. “May I take my tulips now?”

“Of course. Shall you want them all at Oxford?”

“Send the Flame tulips to my London house, my wife can plant them for me there. But the rare tulips and the Violetten I must have beside me.”

“If you breed a true violet one then do let us know,” Hester said, gesturing to Joseph to take the sack of labeled rare tulips out to the wagon waiting in the street beyond the garden gate. “We would buy one back from you.”

“I shall present it to you,” John Lambert said grandly. “A mark of respect to another guardian of treasure.” He glanced down the garden and saw Johnnie. “And how’s the cavalry officer these days?”

“Very disheartened,” Hester said. “Would you let him make his bow to you?”

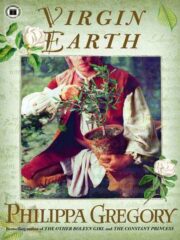

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.