There was nothing for the two men to do. A couple of times there was a knock at the door and John went to admit a visitor to the rarities room and one to walk around the garden; but the rest of the time he and Alexander sat in silence in the parlor, either side of the cold fireplace, straining to hear footsteps upstairs, waiting for news. Johnnie took up a position on the top of the stairs outside Frances’s room carving at a twig with his pocketknife. All the day, he sat like a little choirboy at a vigil, listening to the gentle murmur of talk and the irregular sigh of Frances’s breath.

There was little Hester could do, though she never left Frances’s bedside. She sponged her forehead with vinegar and lavender water, she changed the sheets when they grew wet with sweat, she held her hand and spoke to her quietly and reassuringly when Frances tossed in fever-colored nightmares, and she held her shoulders so that the young woman could sip a drink of cool well water.

But when Frances dropped back on her pillows and lay still, and the flush died away from her cheeks and her skin grew waxy and pale, there was nothing Hester could do but sit at the head of the bed and pray that her stepdaughter would live.

Hester watched all the night at the bedside and at three in the morning her head drooped and she slept. She was wakened only a few minutes later by a movement in the bed and she heard Frances say, “Oh Hester!” in a tone of such sorrow that she was awake and on her feet as her eyes opened.

“What is it? Have you found a swelling?” she demanded, naming the greatest fear.

“I’m bleeding,” Frances said.

Hester saw at once that the fever had broken but the young woman was white and drained, and her nightdress was stained a deep cherry red.

“My baby,” Frances whispered.

Hester twisted a strip of sheet and held it against the flow. “Lie quietly,” she said urgently. “I’ll send John for the midwife, you may be all right.”

Frances lay back obediently, but shook her head. “I can feel it gone,” she said.

Hester, a childless woman, felt herself adrift in a tragedy that she had never experienced. “Can you?”

“Yes,” Frances said, in a little voice which Hester recognized from the lonely little girl she had first met. “Yes. My baby’s gone.”

At seven in the morning Hester went wearily downstairs with a pile of cloths for burning and some sheets to wash, and found Alexander Norman and John alert and silent at the foot of the stairs.

“Forgive me,” she said slowly. “I forgot the time, I forgot that you would be waiting and worried.”

John took the bundle from her and Alexander took her hand. “What’s happened?” John demanded.

“The fever has broken and she has no swellings,” Hester said. “But she has lost the baby.” She looked at Alexander. “I am sorry, Alexander. I would have sent for the midwife but she was sure that it was too late. It was all over in a moment.”

He turned and looked up the stairs. “Can I go to her?”

Hester nodded. “I’m sure it’s not the plague, but don’t wake her, and don’t stay long.”

He went up the stairs so quietly that the treads did not squeak. John dropped the laundry on the floor and enfolded his wife in his arms. “You haven’t slept at all,” he said gently. “Come. I’ll give you a glass of wine and then you must go to bed. Alexander can look after her now, or me, or Cook.”

She let him draw her into the parlor, seat her in a chair and press a glass of sweet wine into her hand. She took a sip and some of the color came back into her cheeks. She had never looked more plain than now, when she was strained and weary. John had never loved her better.

“You cared for her very tenderly,” he said. “No mother could have done better.”

She smiled at that. “I could not love her more if I had given birth to her myself,” she said. “And I have long thought that she has two mothers: Jane in heaven and me on earth.”

He took the chair beside her and he drew her onto his knee. Hester wound her arms around his neck and laid her head on his shoulder and for the first time allowed herself to weep for the baby that was lost.

“There will be other babies,” John said, stroking her hair. “We will have dozens of grandchildren, from Frances, from Johnnie.”

“But this one is lost,” Hester said. “And if it had been a boy she was going to call him John.”

Summer 1646

Frances stayed at the Ark for all of the summer, promising Alexander that she would not return to his house in the City until the cold autumn weather had frozen out the plague. But they were not parted for many nights. The fighting was over and there was little demand for barrels for gunpowder. Many evenings Alexander took a boat from the Tower running with the incoming tide up the river to Lambeth, and then strode down the lane to the Ark to see his wife sitting on the front wall, waiting for him as if she were still a little girl.

It was a bad year for sickness, as everyone had predicted, and the town was full of soothsayers and prophesiers and men and women who were prepared to stand up and give witness on street corners that while the king was with the Scots, who had taken him away to Newcastle, the nation could not be at peace. The king must come to London and explain himself, the king must come before the widows and fatherless children and beg their pardons, the king must come before Parliament and agree how to live in peace with them. What the king should not do was to continue debating, sending arguments to Parliament in favor of himself, discussing theology with the covenanting Scots and generally enjoying his life as blithely and as happily as if the country had not battled for years and got nowhere.

“He can’t be happy.” John disagreed with Johnnie, who brought back this news from Lambeth market. “He can’t be happy without the queen and without the court.”

“He only has to wait and Montrose will rescue him!” Johnnie declared. “The Scots are his enemy, he has played a clever game by going to them. They shield him from his enemies, the English Parliament, and all the time he is waiting for Montrose. Montrose will fight his way across the Highlands for the king.”

“Johnnie has a new hero,” Hester told her husband with a smile. She was checking the purchases off the back of the wagon and Cook was taking them into the kitchen. “He was all for Prince Rupert but now it is Montrose.”

“They say no one will ever catch him, that he runs around the Highlands like a deer,” Johnnie said. “The Covenanters will never catch him, he’s too quick and too clever. He knows all the passes through the mountains, when they wait for him at one place he melts away over the hills and then attacks them in another.”

“It always sounds so easy when it is told like a ballad,” John said soberly. “But real battles are not so quick. And real defeats can make a man sick to the heart.”

Johnnie shook his head and would not be persuaded then; but later in the summer he tasted a little of the bitterness of defeat. He spent the day of 25 June at the little lake, rowing his boat around in aimless circles. The king’s town of Oxford had surrendered and Prince Rupert – the darling of the court, the hope of the royalists, the most dashing, the most glamorous, the most beautiful general that the war had seen – was sent out of the country into exile and would never be allowed to return.

Hester went down to the lake at dusk to find Johnnie. It was getting cold and the frogs were croaking in the reeds at the side of the pond and the bats dipping like nighttime swifts to snatch the insects that still danced over the gray waters. She could just see the little rowboat with the oars shipped and Johnnie curled up in the stern, with his long legs trailing over the side of the boat and the heels of his boots dipping in the water and making circular ripples like rising fish.

“Come in,” she called, her voice gentle across the still water. “Come in, Johnnie. The war is over and that’s a thing to be glad for, not a matter of grief.”

The little huddled figure in the boat did not move.

John came down the path and stood beside Hester.

“He won’t come in,” she said.

John took her hand. “He will.”

She resisted him as he tried to draw her away. “He has adored Prince Rupert for years. He cried the night Rupert lost Bristol.”

“He’ll get hungry,” John said. “There is loyalty and love and there is a thirteen-year-old boy’s belly. He’ll come in.” He raised his voice. “We have some strawberries for dinner tonight. And Cook has made marchpane pastry to go with them. Have we got some cream too?”

“Oh yes,” Hester said clearly. “And a rib of beef with Yorkshire pudding and roasted potatoes and the allspick lettuce.”

There was a small movement from the becalmed boat.

John tucked Hester’s arm firmly under his elbow and drew her away from the bank of the pond.

“I don’t like to leave him,” she whispered.

John chuckled. “If he’s not in by the time dinner is on the table you can send me to swim out to him,” he said. “It’s a pledge.”

John could make light of Johnnie’s despondency at the news of Prince Rupert’s exile, but the thought of the king in the hands of the Scots at Newcastle haunted him too. In July there was news of an English mission to try to persuade the king to come to agreement with Parliament, and all the time the king was being worked on to sign a treaty with the Scots.

“If he cannot agree with either the English or the Scots, what will become of him?” John asked Hester. “He has to give up either his right to the army and come home to England, or give up his religion and join the Scots. But he can’t just wait and do nothing.”

Hester said nothing. She thought the king was perfectly capable of waiting and doing nothing while the queen campaigned for him in France, Montrose risked his life and his men in the Highlands and Ormonde tried to fight his way through a maze of the king’s own self-betraying plotting in Ireland. “If the Irish were to come over and join with Montrose and fight for the king-” she suggested.

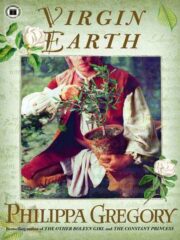

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.