One glance at her face told him that she was terrified. “Oh, I don’t mind,” she said. “Johnnie loves it.”

John gave a short bark of laughter. “Then Johnnie can do it,” he said firmly. “You and I will land at the Swan Stairs like Christians and Johnnie can meet us on the other side.”

“But I like Mother coming too!” Johnnie protested.

“That’s as may be,” John said firmly. “But I’m home now, and you’re not going to drown my wife to keep you company. You can shoot the bridge on your own, my boy.”

The ferryman set them ashore at the steps. John put his hand under Hester’s elbow as they climbed to the top and turned to wave to Johnnie as he sat in the prow of the boat to gain full pleasure from the terrifying ride.

“Look at his face!” Hester exclaimed lovingly.

“You are too indulgent to him,” John said.

She hesitated. John was his father and the head of the household. Restoring the power to him was hard for her, just as regaining his position was for him. “He’s still only a boy,” she remarked. “Not yet thirteen.”

“If he was in Virginia-” John started and then bit back the rest.

“Yes,” she said softly. “But he isn’t. He’s a good boy and he has been courageous and faithful through these difficult years. If he was a planter’s son, living in the wilds, then I dare say he would be a quite different boy. But he is not. He is a boy who has had to have his childhood in the middle of a war and he has seen all of the adults around him most terribly afraid. You are right to restore the rules, John, but I won’t have him blamed for not being something he has no business to be.”

He turned and faced her but she did not drop her gaze. She stared at him fiercely as if she did not care whether he beat her or sent her home in disgrace. Not for the first time John was reminded that he had married a redoubtable woman and, despite his temper, he remembered also that she was fiercely defending his son, just as she had fiercely defended the garden and the rarities.

“You’re right,” he said, with the smile she loved. “And I will be restored to my place at the head of the household. But I won’t be a tyrant.”

She nodded at that, and when they strolled together to the other side of the bridge where the boat was waiting she slid her hand in the crook of his arm and John kept it there.

They paid the boatman and retraced their steps to the Tower. Alexander Norman’s timber yard was beside the walls of the Tower on the grounds of a former convent. His house was built alongside, one of the long, thin town houses pressed against the narrow street. Hester had feared that Frances would be unhappy without a garden, with little more than a dozen pots in the cobbled yard at the back, which was overshadowed half the day from the stacks of wood in the timber yard next door. But already the house was draped in climbing roses and honeysuckle was growing up to the very windows, and every window had a bracket fixed outside and a square planting box nailed to the wall with a row of tulips waiting to bloom.

“I’d have no trouble guessing which house was hers,” John said grimly, glancing down the street at the other bare-fronted, barefaced houses.

“That’s nothing,” Johnnie said with pleasure. “She has an herb garden out the back and an apple tree squashed against the back wall. She says she’ll prune it to keep it small enough. She says she’ll repot it every year and prune the roots too.”

John shook his head. “She needs a dwarf apple tree,” he said. “Perhaps if one could graft an apple sapling onto a shrub root it might grow small…”

Hester stepped forward and knocked on the door. At once Frances opened it. “Father!” she said, and slipped down the step, threw her arms around him and laid her head against his shoulder.

John almost recoiled from her touch. In the three years he had been away she had grown from a girl to a woman of nearly eighteen years, and now, with her slight body pressed against him, he could feel the hard swelling of her baby.

He stepped back to see her and his face softened. “You’re so like your mother,” he exclaimed. “What a beauty you’ve become, Frances.”

“She’s the very picture of my Jane.” Mrs. Hurte emerged from the house and shook John and then Hester by the hand. She enveloped Johnnie in a breathtaking embrace but never stopped talking. “The very picture of her. Every time I see her I think she has come back to us again.”

“Come inside,” Frances urged. “You must be frozen. Did you shoot the bridge?”

“Father wouldn’t let Mother come.”

Frances shot a brief approving look at her father. “Quite right. Why should Mother risk drowning because you like it?”

“She likes it!” Johnnie protested.

“I swear I never said so,” Hester remarked.

Mrs. Hurte surged outward rather than into the house, took John by the arm and drew him aside. Hester silently admired the tactical skill of her stepdaughter. This was generalship as gifted as Oliver Cromwell’s with his New Model Army. Mrs. Hurte would change John’s mind in favor of the match in two sentences of complaints. Both Hester and Frances strained their ears to hear her do it.

“You’re home too late,” Mrs. Hurte said reproachfully to John. “This is a bad business, and you too late to prevent it.”

“I don’t see that it is bad,” John remarked.

“A man of fifty-six and a girl of seventeen?” Mrs. Hurte demanded. “What life can they have together?”

“A good one.” John gestured to the pretty house and the tracery of carefully pruned rose branches. “A boy of her own age could not hope to give her so much.”

“She should have been kept at her home.”

“In these times?” John asked. “Where safer than beside the Tower?”

“And now expecting a baby?”

“The older the bridegroom, the sooner the better,” John rejoined swiftly. “Why should you be so against it, Mother? It was a marriage for love. Your own daughter Jane had nothing less.”

She bit her lip at that. “Jane brought a good dowry and you two were well matched,” she said.

“I will see that Frances is properly dowered when peace is restored and I can sell the Virginia plants and restore the rarities to their proper place,” John said firmly. “I am trading in a small way with the West Indies and I expect to see a profit on that very soon. And Frances is well-matched. Alexander is a good and faithful friend to this family and she loves him. Why should she not marry the man of her choice in these times when men and women are making their own choices every day? When this whole war has been fought for men and women to be free?”

Mrs. Hurte smoothed her somber gown. “I don’t know what Mr. Hurte would have said.”

John smiled. “He would have liked the house, and the business. Cooper for the ordinance in the middle of a war? Don’t tell me that he wouldn’t have loved that! Alexander is earning twelve pounds a year and that’s before he draws his allowances! It’s a fine match for the daughter of a man who has little to sell and most of his stock in hiding.”

Hester and Frances exchanged a hidden smile, turned and went into the house.

“That was clever,” Hester said approvingly to her stepdaughter.

Frances gave her a most unladylike wink. “I know,” she said smugly.

Spring 1646

When the soil warmed in April and the daffodils came out in the orchard and the grass started growing and the boughs of the Tradescant trees were filled with birds singing, courting and nest building, John strode around the brick chip paths in his new Papist boots and learned to love his garden again. He made a special corner for his Virginian plants and watched as the dried roots put up tiny green shoots and the unpromising dry seeds sprouted in their pots and could be transplanted.

“Will they do well here?” Johnnie asked. “Is it not too cold for them?”

John leaned on his spade and shook his head. “Virginia is a place of far greater extremes than here,” he said. “Colder by far in winter, hotter in summer, and damp as a poultice for month after month in summer. I should think they will thrive here.”

“And what will sell the best, d’you think?” Johnnie asked eagerly. “And what is the finest?”

“This.” John leaned forward and touched the opening leaves of a tiny plant. “This little aster.”

“Such a small thing?”

“It’s going to be a great joy for gardeners, this one.”

“Why?” Johnnie asked. “What’s it like?”

“It stands tall, almost up to your waist, and white like a daisy against thick, dark leaves, a woody stem, and it grows in profusion. It’s a kind of shrubby starwort, like the aster from Holland. In Virginia I have seen a whole forest glade filled with them, like the whiteness of snow. And I once saw a woman plait the flowers into her black hair and I thought then it was the most beautiful little flower I had ever seen, like a brooch, like a jewel. I might name it for us, it’s just the sort of little beauty that your grandfather would have liked, and it will grow for anyone. He liked that in a plant. He always said that it was the hardy plants that gave the greatest joy.”

“And trees?” Johnnie prompted.

“If it grows,” John cautioned him. “This may be our finest tree from Virginia. It’s a maple tree, a Virginian maple. You can tap it for sugar, you put a cut in the trunk in springtime, when the sap starts rising, and the sap oozes a juice. You collect it and boil it down and it makes a coarse sugar. It’s a great delight, to set a little fire in the woods and boil down the syrup, all the children lick up the spills and run around with sticky faces and…” He broke off, he couldn’t bear to tell his boy about the other – Suckahanna’s boy. “The leaves turn the deepest, finest scarlet in the autumn,” he concluded.

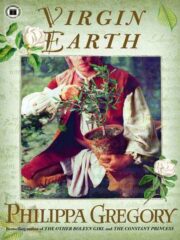

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.