It was as if the heart had gone out of her and out of the house altogether. The garden was neglected, the topiary and the knot garden hedges were growing out and losing their shape. The gravel on the paths was no defense against the constantly springing weeds. The warm nursery beds by the house had not been prepared with sieved earth for the coming of the new season as they should have been. The fruit trees had not been properly pruned in the autumn. Even the chestnuts had not all been planted and grown on ready for sale in the early summer.

“I couldn’t do it all,” Hester said stubbornly as she saw John look critically over the garden from the terrace. “I had no boys, I had no money. We all did what we could but this garden takes a dozen men to keep. Joseph and Johnnie and Frances and I couldn’t do it.”

“Of course not, I understand,” John said and he turned away to brood in the half-empty rarities room, and walk with his limping stride around the frozen garden.

Johnnie unpacked the Virginian saplings and left them in their barrels by the house wall. The ground was too hard to dig them in. One of them had died from the salt winds of the voyage but the other four looked strong and likely to put out green leaves when the weather improved.

“What are they?” Johnnie asked.

His father’s face lit up. “Tulip trees, they call them. They grow as round and shapely as a horse chestnut but they have great flowers, white, waxy flowers, as big as your head. I have seen them grow to such a height and breadth-” He broke off. Suckahanna had showed it to him. “And these are maple trees.”

Johnnie rolled the big barrels of seeds and roots into the orangery and set to work unpacking them and planting them up in pots of sieved earth ready to be set outside and watered when the spring frosts ended. John watched him, disinclined to work himself, horribly quick to criticize when his son dropped a seed or was clumsy with a root.

“Have you never been taught how to do this properly?” he demanded irritably.

His son looked up at him, his resentment veiled. “I am sorry, sir,” he said formally.

Hester appeared in the doorway and took in the scene in one quick glance. “Can I have a word with you, husband?” she asked, her voice very even.

John walked toward her and she drew him out of earshot, into the garden.

“Please don’t correct Johnnie so harshly,” she said. “He’s not used to it, and indeed he is a good boy and a very hard worker.”

“He is my son,” John pointed out. “I shall teach him what is right.”

She bowed her head. “Of course,” she said coldly. “You must do as you wish.”

John waited in case she should say any more and then he flung himself away from her and stamped into the house, his feet hurting in his boots, knowing himself to be in the wrong, not knowing how to make things right.

“I shall go to London,” he said. “I shall complete my commissions for Sir Henry. It’s clear that we have to make our fortune some other way than by the garden and the rarities since the rarities are gone and the garden half-ruined.”

Hester went back into the orangery. Johnnie raised his eyebrows at her.

“We all have to become acquainted with each other again,” she said as equably as she could. “Let me help you with that.”

For days John walked around the grounds, trying to accustom himself to the smaller scale of England, trying to accept a horizon which seemed so very close, trying to enjoy his continuing ownership of twenty acres when he had been free to run in a forest which went on forever, trying to be glad of a plain, forthright wife and a bright, fair son and not to think of the dark beauty of Suckahanna and the animal grace of her boy. He arranged the Indian goods in the half-empty rarities room, feeling the arrowhead come so easily into his hand, rubbing the buckskin shirt between his finger as if something of the warmth of Suckahanna’s skin might still linger.

He made a little money on his commission for Sir Henry and he bought a couple of fine paintings, crated them up and sent them out to him. When the ship came back, in four months’ time or so, it would bring him another note of credit and perhaps some more barrels of sugar for John to sell. He drew some satisfaction from being able to make some money, even in these difficult times, but he thought he might never feel a sense of freedom or joy ever again.

Hester did the only thing she knew how to do, and tackled the practical problems of the situation. She asked him to walk with her to Lambeth and took him straight to the best bootmaker still working in the village. He measured John’s feet and then looked at the bare soles with horror. “You have feet like a Highlander, if you’ll excuse me saying so.”

“I had to go barefoot. I was in Virginia,” John said shortly.

“No wonder all your boots pinch,” the cobbler said. “You have no need of boots at all.”

“Yes he does,” Hester remarked. “He’s a gentleman in England and he’ll have a pair of boots of best leather, a pair of working boots and a pair of shoes. And they’d better not pinch.”

“I haven’t the leather,” the man said. “They don’t drive the cattle to Smithfield, the tanners can’t get the hides, I can’t get the leather. You’ve been in Virginia too long if you think you can order shoes like the old days.”

Hester took the cobbler by the elbow and there was a brief exchange of words and the clink of a coin.

“What did you offer him?” John asked as they emerged from the dark shop into the bright March sunlight.

Hester grimaced and prepared for a quarrel. “You won’t like it, John, but I promised to supply the leather from your father’s rarities. It was only some leather painted with a scene of the Madonna and Child. Not very well done, and completely heretical. We would invite the troops upon us if we ever showed it. And the man is right, he can’t get leather for your shoes otherwise.”

For a moment she thought he was going to flare up at her again.

“So am I to strut around London with Papistical images painted on my boots?” he asked. “Won’t they hang me for a Jesuit in hiding?”

“Not much of a disguise if you’re going around with the Virgin Mary on your feet,” Hester pointed out cheerfully. “No, the painting is almost worn off, and he’ll use it on the inside.”

“We are using rare treasures as household goods? What kind of stewardship is this?”

“We are surviving,” Hester said grimly. “Do you want boots that you can walk in or no?”

He paused. “Do you swear that nothing else of any merit is missing from the collection?” he demanded. “That it is safe in hiding as you say?”

“On my honor, and you can see it all for yourself if you cut down the tree and open the door. But John, you had best wait. It’s not safe yet. They all say the king is defeated but they have said that before. He has his wife working against us in France, and the Irish to call on, and who knows what the Pope might order if the queen promises to hand over the country to Popery? The king cannot be defeated in battle, for all that they fight and fight. Even when he is down to his last man he is not defeated. He is still the king. They cannot defeat him. He has to decide to surrender.”

John nodded and they fell into stride together for the short walk home. “I keep thinking. I keep wondering – perhaps I should go to him,” he said.

She stumbled at the thought of him returning to the court and to danger. “Why? Why on earth would you go?”

“I feel almost that I owe him some service,” he said.

“You left the country to escape serving,” she reminded him.

He grimaced at her bluntness. “It wasn’t that simple,” he said. “I didn’t want to die for a cause I can’t believe in. I didn’t want to kill a man because like me he had halfheartedly joined, but on the other side. But if the king is ready for peace then I could serve him with a clear conscience. And I don’t like to think of him alone at Oxford, without the queen and with the prince fled to Jersey, and no one with him.”

“There’s a whole crowd with him,” Hester said. “Drinking themselves senseless every night and shaming Oxford with their behavior. He is in the thick of company. And if he sees you he will only remember you and ask where you have been. If he wanted you he would have sent for you by now.”

“And has there been no word?”

She shook her head. “Since they wanted us to serve under the Commission of Array there has been nothing,” she said. “And they risked our lives for a lost cause then. There is nothing you can do for the king unless you can persuade him to come to terms with his people. Can you do that?”

“No.”

As soon as John’s new boots were ready he put them on, dressed in his best suit and announced his intention of formally visiting his daughter in her new home. Hester and Johnnie, also dressed in their best, went with him in the boat downriver.

“Will he be angry?” Johnnie asked under the noise of the oars in the water.

“No,” Hester said. “The moment he sees her she’ll have him wrapped around her finger like always.”

Johnnie chuckled. “Can we shoot the bridge?” he asked.

Hester hesitated. Timorous passengers would make the ferrymen leave them on the west side of Tower Bridge and walk round to rejoin their boat at the other side. The currents around the pillars of the bridge were terrifyingly swift and when the tide was on the ebb and the river was full, boats could overturn and people could drown. It was Johnnie’s great passion to shoot the rapids and generally Hester would stay in the boat with him, her hands gripping the side, her knuckles white, and a smile firmly fixed on her face.

“Do what?” John asked and turned around.

“Shoot the bridge,” Johnnie replied. “Mother lets me.”

John looked in surprise at his wife. “You can’t enjoy it?” he asked.

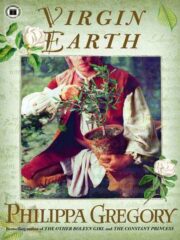

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.