“I am nearly eleven!” he protested. “And the head of the household.”

Hester gave him a small smile. “Then stay and defend me,” she said. “We hold the treasures of the country here. We need to stay at our post.”

He was a little mollified. “When I am a man I shall train and join Rupert’s cavalry,” he promised.

“I hope that when you are a man you will be a gardener in a peaceful country,” she said fervently.

At the end of March there was extraordinary news which came into the city as gossip and was confirmed within the day in broadsheets and pamphlets and ballads. Despite all premonitions and fears, despite all likelihood, the Parliament army, working men officered by those who had never been gentlemen at court, had met the king’s army at Alresford outside Winchester, fought a long, hard battle and won a resounding victory. It was all the more impressive because the battle had turned on a cavalry charge by the royalists which, for once, did not end in a rout of terrified Parliament infantry being cut down as they fled. This time the Parliament men stood their ground, and the king’s horse, thrown back into the twisting, deep lanes of Hampshire, could not come around again, could not regroup, while the Parliamentary infantry doggedly and determinedly slugged their way uphill to Alresford ridge, and were in Alresford before nightfall.

There were bonfires all over Lambeth that night, and precious candles showed at every window. The next Sunday there was not a man, woman nor child who did not attend a service of thanksgiving. The tide of the war had ebbed for a moment, for a moment only; and no cavaliers would be riding through the narrow streets of Lambeth for a month or two at least. And there would be no Papist Irish murdering soldiers either. The news came filtering through that the Parliamentary forces had captured all the Irish-facing ports of Wales. The king could not bring the Papists into England. Even in Scotland the small royalist forces were being driven back.

“I think the king will have to come to terms with Parliament,” Alexander said to Hester one evening in April. “He’s on the defensive for the first time and the royal army is not one which fights well in retreat. He doesn’t have the advisers or the determination to carry on.”

“And what then?” Hester asked. She had a basketful of sweet pea pods from last year in her lap and she was shelling the seeds ready for planting. “Do I unpack the rarities from their hiding places?”

Alexander considered for a moment. “Not until peace is declared,” he said. “We’ll wait and see. It may be that the tide is turning at last.”

“D’you think the king will make peace with Parliament and come meekly home?”

Alexander shrugged. “What else can he do?” he said. “He has to come to terms with them. He is still king: they are still Parliament.”

“So all this pain and bloodshed has been for nothing,” Hester said blankly. “Nothing except to teach the king that he should manage his Parliament as his father and the old queen managed theirs.”

Alexander looked grave. “It’s been an expensive lesson.”

Hester threw a handful of dried empty pods into the fire and watched them spark and flare up. “Damnable,” she said bitterly.

April 1644, Virginia

John had hoped that he had been summoned to Opechancanough’s war council as a simple brave, companion to Attone. But as the days wore on at the town of Powhatan he found he was summoned every morning to speak with Opechancanough. At first the questions were pointed and direct. The fort at Jamestown: was it true that the town had grown so large that all the people could not fit inside the walls? Was it true also that the walls had been allowed to fall into disrepair, that a proper watch was no longer kept, that the cannon were rusty?

John answered as truly as he knew, warning Opechancanough that he had been nothing more than a visitor passing through Jamestown, and not a resident who knew the town inside out. But as the questions went on Opechancanough revealed that he knew the answers as well as John. The wise old commander had many spies watching the fort. He was using John as a check against them, and they against him. He was testing John’s own ability to tell the truth, proving his loyalty to his adopted people.

Once he was satisfied that John would honestly tell him all that he knew, then the questions changed. He asked instead what hours the white men rose in the morning, what they drank for their breakfast, if they were all drunkards, half-drowned in fiery spirits by the time darkness fell. Did they have a special magic in their use of gunpowder, cannon, or flintlock, or could the Powhatan people seize these goods and turn them against their makers? Was the god of Englishmen attentive to them in this foreign land, or might He simply forget them if the real people rose up against them?

John struggled with the concepts of magic, warfare, and theology in a foreign language, and in a different way of thinking. Over and over again he found himself saying to the older man, “I am sorry, I don’t know,” and saw the dark brows snap together and the crumpled face darken with anger.

“I really don’t know,” John would say, hearing the nervousness in his own voice.

Over and over again Opechancanough would return to the English communications. If a settler discovered the uprising, how quickly could he take the news to Jamestown? Did the English have a method of sending signals in smoke? Or a code of drums?

“Smoke?” John asked disbelievingly. “No. Nor drums. Soldiers only drum the march forward or the retreat…”

Opechancanough spat derisively. “No. To send messages. Long messages.”

John shook his head in bewilderment. “Of course not. How could you do such a thing?”

Opechancanough’s dark smile gleamed. “Never mind. So if a man was warned and wanted to take the warning to Jamestown, he would have to go himself? By foot or canoe?”

“Yes,” John replied.

There was silence for a moment. “In the last war we were betrayed,” Opechancanough said thoughtfully. “It was a couple of our boys who had been treated kindly by their white master and could not bear to hurt him. They warned him. They had grown soft like white boys. They thought they would save him alone; but in warning him they betrayed every one of us. He ran to Jamestown and warned the fort so they were ready for us. And what of the boys who loved their master so much that they betrayed their own people and warned him?”

John waited.

“Shot by the white men,” Opechancanough said. “That is how the white men reward a faithful servant. We saw it done. And those of us who had fought, and those of us who had not, were all driven further and further away from our villages and watched our fields hoed for tobacco, nothing but tobacco, everywhere the plant for smoke and nothing for life.”

“When will the new war be?” John asked.

Opechancanough shrugged. “Soon.”

John woke in the night and lay still. Something had disturbed his sleep but he could not trace the noise or the movement or the sense which had woken him. Then he heard it again. From outside the house a twig cracked, and then the skins at the doorway parted and a low voice spoke briefly into the warm darkness: “It is now.”

Attone at John’s side was awake and standing. “Now!” he said, and his voice was filled with joy.

“What is now?” John asked, as if he did not know, as if he were not near to sinking down on the ground and weeping into the earth for his sense of dread and guilt.

“We are on the warpath,” Attone said gently. “It is now, my brother.”

Outside the tent the town was in alert silence. Men were stringing their bows and tightening their belts, checking the gleam of the blades of their knives. There was nothing to prepare, for the Powhatan were always ready for travel, for hunting, for war. John fell into line behind Attone and knew that his breath was sluggish and slow beside Attone’s light panting, knew his heart was not in this, knew also that there was no way forward and away from his allegiance to the Powhatan, and no way backward to the English.

At a signal from Opechancanough, seated on his throne, dark as a shadow in the moonlight, the men moved off, making as little noise as a herd of wolves, silent in their moccasins, their quivers held still at their sides, their bows strung over their shoulders. The moonlight touched each one like a benison, the white gleam falling on a feather plaited into dark hair, on a pale old scar on one high cheekbone, on a smile of excitement, on the gleam of burnished skin. John went silently in Attone’s steps, watching the pace of his moccasins, the movement of his haunches beneath the leather skirt, concentrating wholly on the moment of the journey so he could hide from himself the knowledge of the destination.

They were to split into two main parties. One was to travel by canoe downriver to Jamestown, taking advantage of the night to move swiftly and to form a pincer around the town by dawn. The other was to go by land either side of the river, and at every house and cabin, every grand, ambitious building and hopeful shack, they were to go in and kill every man, woman and child in the place, leaving none to escape, and none to take the news downriver.

John was in the land party, Attone with him. He thought that Opechancanough was testing his loyalty to the Powhatan by putting him in the group that would kill so early and so immediately – and not against the fighting men at the fort, but against the vulnerable, sleeping men and women with their children bundled up in the same bed beside them. But then he realized that Opechancanough had placed him where, if he were faithless, he could do no damage. He was at the rear, he could not dash ahead and warn Jamestown. All he could do was botch a few killings upriver and get himself shot.

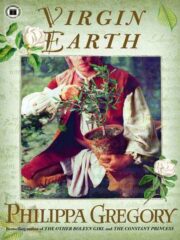

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.