She went out slowly to meet him. “What’s wrong?”

He shook his head but he would not meet her eyes. “Nothing. I have done what I promised to do and now I am come home. I need not go again until harvest time.”

“Are they sick?” she asked, thinking that his slouch might be shielding some illness or pain.

“They are well,” he said.

“And you?”

He straightened up. “I am weary,” he said. “I shall go to the sweat lodge and then wash in the river.” He gave her a brief unhappy smile. “And then everything will be as it was.”

In the warm days when the woods seemed to grow and turn green before his very eyes, John returned to his trade of plant collecting and rarity hunting. Already he had sent home a large parcel of Indian goods: clothing, tools, a case of bands and caps made from bark; now he recruited Suckahanna’s son as his porter and every day the two of them left the village for a long stroll in the woods and came back laden with sprouting roots. John worked in companionable silence with the boy, and found that his thoughts often wandered to Lambeth. He felt great affection for Hester and a powerful sense that he should be there with her, to face whatever dangers might come from a country in the grip of an insane war. But at the same time he knew he could not leave Suckahanna and the Powhatan. He knew that his happiness, and his life, lay with the People.

John thought himself a fool: to abandon a wife and then to try to support her, to take a wife and then to think daily of her rival. He wanted so much to be a man like Attone, or even a man like Hobert, who saw life in simple terms, who saw one road and steadily walked it. John did not think of himself as complex and challenged; he lacked all such vanity. He saw himself as indecisive and weak and he blamed himself.

Suckahanna watched him create a nursery bed, heel in the roots, and linger over his cuttings; but she said nothing for many weeks. Then she spoke.

“What are they for?”

“I shall send them to England,” John said. “They can be grown and sold there to gardeners.”

“By your wife?”

He tried to meet her direct black gaze as frankly and openly as he could. “My English wife,” he corrected her.

“And what will she think? When a dead man sends her plants?”

“She will think that I am doing my duty by her,” John said. “I cannot abandon her.”

“She will know that you are alive, and that you have abandoned her,” Suckahanna observed. “Whereas now she may have given you up for dead.”

“I have to support her in the way that I can.”

She nodded and did not reply. John could not accept the stoical dignity of the Powhatan silence. “I feel that I owe her anything that I can do,” he said awkwardly. “She sent me a letter which I got at Hobert’s house. She is in difficulties and alone. I left her to bring up my children and to manage my house and garden in England, and there is a war in my country…”

Suckahanna looked at him but said nothing.

“I am torn,” John said with a sudden burst of honesty.

“You chose your path,” she reminded him. “Freely chose it.”

“I know,” he said humbly. “But I keep thinking…”

He broke off and looked at her. She had turned her head away from him, hiding her face with a sweep of black hair. Her shoulders, showing brown and smooth through the veil of black hair, were shaking. He gave an exclamation and stepped forward to comfort her, thinking that she was weeping. But then he saw the gleam of her white teeth against her brown skin, and she flicked around and was running down the village lane, away from him, and was gone. She had been laughing. Not even her immense courtesy could restrain her amusement any longer. The spectacle of her husband struggling interminably forward-backward, duty-desire, English-Powhatan, was in the end too helplessly funny for her to take seriously. He heard the wild ripple of her laugh as she ran down the path to the garden where the sweet corn was already growing high.

“Aye, you can laugh,” John said to himself, feeling himself wholly English, as leaden footed as if he were wearing boots and breeches and weighed down by a hat. “And God knows I love you for it. And God knows I wish I could laugh at myself too.”

When the snows were melted from even the highest hills, when there were no sharp frosts in the morning, when the ground was dry beneath the light summer moccasins of the braves, there was a meeting called by the ancient lord, Opechancanough. John the Eagle went with Attone and with one of the senior advisors of the community to represent their village, traveling along the narrow trails, northward up the river to the great capital town of Powhatan. It nestled in the dry woodlands, at the foot of the mountains on the edge of the river which John had once known as the James River, but which he now called the Powhatan, and the waterfall at the side of Powhatan town was Paqwachowing.

They sighted the town of about forty braves at dusk, and paused outside the city boundaries.

“You’re to keep quiet until spoken to,” Attone said briefly to John. “The elder will do the talking.”

John looked without resentment at the older man who had led the way at a hard pace for the journey of many days. “I didn’t even want to come,” he protested. “I’m hardly likely to interrupt.”

“Didn’t want to come, when you can see new plants and trees and flowers? And take them back to Suckahanna when we sail downriver by canoe?” Attone mocked.

“All right,” John allowed. “But I’m saying I didn’t ask to come. I didn’t want a place here.”

The older man’s sharp beaky face turned to him. “But your place is here,” he said.

“I know it, older one,” he said respectfully.

“You will answer questions but not give opinions,” the man ruled.

John nodded obediently and fell into file at the rear.

No one knew the age of the great warlord Opechancanough. He had inherited his power from his brother the great Powhatan, father of Princess Pocahontas, the Indian heroine whom John had visited when he had been only a little boy and she had been a celebrity visiting London. There was no trace of her beauty in the ravaged face of her uncle. He sat on a great bench at the end of his luxurious long house, his cape of office shining in the gloom with the round discs of abalone shells. He barely glanced at John and his companions as they shuffled up, bowed, deposited their tribute on the growing pile before him, and stepped back.

When everyone had come and bowed to the lord he made a brief gesture with his hand and the priest stepped forward, cast some dust into the fire and watched the scented smoke spiralling upward. John, weary from many days’ walking, watched the smoke too and thought that it made strange and tempting shapes, almost as if one could read the future from it, just as he sometimes lay on his back beside Suckahanna’s son when they detected shapes and images in the clouds that sailed overhead.

There was a deep mutter from the massed men packed tight into the big house. The priest walked around the fire, people leaning away from the sweep of his cape as he circled, staring into the embers. Finally he stepped back and bowed to Opechancanough.

“Yes,” he said.

Suddenly the old man sharpened into life. He leaned forward. “You are sure? We will conquer?”

The priest nodded simply. “We will.”

“And they will be pushed back into the sea where they came from, and the waves will foam red with their blood and their women and children will hoe our fields and serve us where we have served them?”

The priest nodded. “I have seen it,” he said.

Opechancanough looked past the priest at the men, waiting in silence, drinking in the assurance that they were unbeatable. “You have heard,” he said. “We will win. Now tell me how this victory is to be won.”

John had been dizzy with the scent of the smoke and the sudden warmth and darkness of the hut but suddenly he snapped awake, wide awake, as if someone had slapped his face. He strained his ears and his comprehension to grasp the quick exchange of advice, argument and information: the news of an isolated farmhouse here, a newly built fort with cannon further down the river. He realized with a sinking heart what he had known all along but had continually pushed to the back of his mind: that Opechancanough and the army of the Powhatan were going to fall upon the people of Jamestown, and upon every white settler everywhere in this country which they had called empty and then proceeded to fill. That if the Powhatan won there would not be a white man, woman or child left alive or out of slavery in Virginia. And if the Powhatan lost there would be a dreadful reckoning to pay.

“And what does our brother, the Eagle, say?” Opechancanough suddenly asked. His beaked harsh face turned toward John, where he sat at the back. The men before him melted away as if Opechancanough’s gaze was a spear thrust pointed at his heart.

“Nothing…” John stammered, the Powhatan language sticking on his tongue. “Nothing… sir.”

“Will they be ready for us? Do they know we have been waiting and planning?”

Miserably John shook his head.

“Did they think us defeated and driven back, forced out of our forests and away from our game trails?”

“I think so,” John said. “But I have not been with the white men for a long time.”

“You will advise us,” Opechancanough ruled. “You will tell us how to avoid the guns and at what time of day we should attack. We will use your knowledge of them to come against them. You agree?”

John opened his mouth but no sound came. He was aware of Attone rising to his feet at his side.

“He is struck dumb by the honor,” Attone said smoothly. Out of sight he trod hard on John’s toes.

“Indeed I am,” John said numbly.

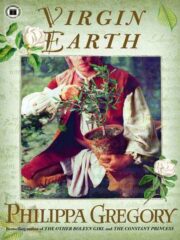

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.