John nodded.

“I buried my brother that year,” Attone said quietly. “My older brother, who was like a father to me. He died with a belly full of frozen grass. There was nothing else to eat.”

John nodded in silence.

“So now before any brave would lift his hand against a white man he would want to know that he has a year’s supply of food in his house. Don’t you think that, my Eagle?”

John gaped. “This is a supply for war?”

The grip on his shoulder tightened so hard it was like a vice. “Did you think we would let them push us into the mountains, into the sea?”

Dumbly, John shook his head.

“Of course there will be war,” Attone said matter-of-factly. “My son has to have a trail to follow. He has to have deer to kill. If the white man will not keep to his treaties, will not share the land, then he will have to be killed.”

John bowed his head. He felt a great sense of impending doom.

“You grieve for your people?” Attone asked.

“Yes,” John replied. “Both of them.”

The deer were fewer, hunting was hard. The men went out in twos and threes, looking for small game and birds. Attone and John left the usual trails and struck out downriver. Suckahanna watched them go, her baby strapped on her back. She embraced John and then she stood back and raised her hand in a respectful salute to her previous husband. He touched his forehead and his heart to her. “Suckahanna, guard my son and daughter,” he said.

“Go safely, both of you,” she replied. “May the trail be smooth under your moccasins and the hunting rich.”

The two men jogged out of the village. John was used to the steady half-running pace of the hunting party now, and his calves no longer seized with cramp as his feet ate up the miles. But it was hard running in the snow. Both men were shiny with sweat when they paused to draw breath and to listen to the quietness of the winter woods all around them.

There was a mild thaw. John could hear a steady drip drip of melting water from trees where dark-stained twigs were at last thickening with buds. Attone’s head was cocked. “What can you hear?” he asked John.

John shook his head. “Nothing.”

Attone raised his eyebrows. He could never become accustomed to the insensitivity of the Englishman.

At once he crouched and his hand went into the gesture with two raised fingers, which meant hare or rabbit. At once John crouched beside him and they both put an arrow on the bow.

It came slowly, quite unaware of their presence. They heard it before they saw it because it was white against the white snow: a winter hare with a coat blanched like ermine. When it dropped on to its haunches the only sign that revealed its presence was the little dimples of dark footprints behind it, and the occasional betraying flick of an ear.

Attone raised his bow and the little thwack of sound as the bow was released was the first thing that alerted the hare. It bounded up and the arrow caught it in the body, behind the foreleg. John and Attone were behind it at once but the animal raced ahead of them, the arrow jinking and diving with it, like a harpoon in a speared fish.

Attone gave a sudden cry as he tripped and fell to the ground. John knew well enough not to check for a moment. He kept running, following the terrified creature, weaving in and out of trees, jumping over fallen logs, diving around rocks, and finally scrabbling on hands and knees through the winter-thin scrub to keep the wounded animal in sight.

Suddenly there was a crack of a musket shot, loud and startling as cannon fire in the icy silence, and John flung himself backward in terror. The hare was thrown into the air and fell down on its back. John rose up from the bushes, half-naked in bear-grease-stained skin and buckskin kilt and jerkin, and looked into the wan, half-starved face of his old friend Bertram Hobert.

He recognized Bertram at once despite the marks of hunger and fatigue on the man’s face. He was about to cry out in greeting but the English words were sluggish on his tongue; and then he realized that Bertram was pointing his musket at John’s belly.

“That’s mine,” Bertram snarled, showing his black and rotting teeth. “Mine. D’you hear? My food.”

John spread his hands in a quick deferential gesture, aware all the time of his razor-sharp reed arrows nestling in the quiver in the small of his back. He could have one on the string and loosed long before Bertram could reload and prime his musket. Was the man mad to threaten with an empty gun?

“Step back.” Bertram waved him aside. “Step back, or by God I’ll shoot you where you stand.”

John went back two, three steps, and watched with silent pity as Bertram hobbled over to the dead hare. There was precious little meat on it, and the rich guts and heart had been blasted out by the shot on to the snow. The silvery pelt, which would have been good to trade, had been destroyed too. Half the hare had been wasted by killing it with a gunshot, whereas Attone’s reed arrow should have gone straight to the heart and left nothing more than a farthing-size hole.

Bertram bent stiffly over the body, picked it up by the limp ears and stuffed it in his game bag. He bared his teeth at John. “Get away,” he said again. “I’ll kill you for staring at me with your evil dark eyes. This is my land, or at any rate, near enough mine. I won’t have you or your thieving people within ten miles of my fields. Get away with you or I’ll have the soldiers out from Jamestown to hunt you down. If your village is near here we’ll find it. We’ll find you and your cubs and burn the lot of you out.”

John stepped back, never taking his eyes from Bertram. The man’s face was a twisted ruin hammered from his old sunny, smiling confidence. John had no inclination to step forward now, to greet his old friend and shipmate by name, to make himself known. He did not want to know this man, this weak, cursing, stinking man. He did not want to claim kinship with him. The man threatened him like an enemy. If his gun had been reloaded John thought that it would have been his blood on the snow, and his belly blasted away like the hare’s. He bowed his head like a servile, frightened, enslaved Indian and backed away. In two, three paces, he was able to lean into the curve of a tree and know that a white man’s eyes would not be able to pick him out from the dapple of white snow and dark tree shadows and speckled bark.

Hobert glared into the shadowy forest which had swallowed up his enemy in seconds. “I know you’re there!” he shouted. “I could find you if I wanted.”

Attone came up beside John so silently that not even a twig cracked. “Who’s the smelly one?” he asked.

“My neighbor, the farmer, Bertram Hobert,” John said. The name sounded strange and awkward on his lips, he was so accustomed to the ripple of Powhatan speech.

“The winter has rotted his feet,” Attone remarked.

John saw that the brave was right. Bertram was painfully lame and instead of shoes or boots his feet were encased in thick wrappings tied with twine.

“That hurts,” Attone said. “He should wear bear grease and moccasins.”

“He does not know,” John said sadly. “He would not know that, and only your people could teach him.”

Attone gave him a quick smile at the unlikeliness of such a meeting and such a lesson. “He has our hare. Shall we kill him?”

John put his hand on Attone’s forearm as he reached for his arrow. “Spare him. He was my friend.”

Attone raised a dark eyebrow. “He was going to shoot you.”

“He didn’t know me. But he helped me build my house when I came to the plantation. We traveled across the sea together. He has a good wife. He was once my friend. I won’t see him shot for a hare.”

“I would shoot him for a mouse,” Attone remarked, but the arrow stayed in his quiver. “And now we will have to cross the river. There will be no game here for miles where he is stamping on his rotting feet.”

They caught no game though they stayed out for three days, traveling along the narrow trails which the People had used for centuries. Every now and then one of the trails would spread itself to double, even treble, the necessary width and then Attone would scowl and look out for a new house being built, a new headright created where this wide path would lead. Again and again they would see a new building standing proud, and facing the river and around it a desert of felled trees and roughly cleared land. Attone would look for a moment, his face expressionless, and then say to John: “We have to go on, there will be no game here.”

They struck away from the river on the second day, since the plantations chose the riverside so that the tobacco could be floated down to the quayside at Jamestown. Once they broke away from the riverbanks things were better for them. In the deeper forest they found traces of deer again and then on the third day, as they were bearing around in a wide circle for home, a great shadowy bush caught Tradescant’s eye and as he watched, it moved. Then he felt Attone’s hand on the small of his back and his breath as he said: “Elk.”

Something in the quiver of the brave’s voice set John’s heart racing too. The beast was massive, its antlers as broad as the outspread wings of a condor. Moving almost unconsciously, John fitted his arrow to his bow and felt the thinness of the shaft and the lightness of the sharpened reed arrowhead. Surely, this would be like shooting peas at a carthorse, he thought. Nothing could bring this monster down.

Attone was moving away from him. For a moment John thought they were to make the traditional pincer movement of deer-stalking, but then he saw that Attone had slung his bow over his shoulder and was climbing the lowest branches of one of the trees. When he was stretched along it with an arrow on the string he nodded to John with one of his darkest smiles.

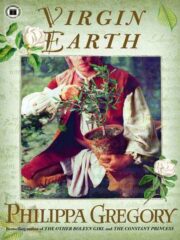

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.