John waited on the bank, his head bowed in respect. He did not think he should join them until he was invited, and anyway, his own strict religious background meant that he shrank in fear for his immortal soul. The story of the Hare and the man and the woman in his bag was clearly nonsense. But was it any more nonsense than a story about a woman visited by the Holy Ghost, bearing God’s own child before kneeling oxen while angels sang above them?

When the people turned and came out of the water their faces were serene, as if they had seen something which would last them all the day, as if they had been touched by a tongue of fire. John stepped forward from the bushes and said in careful Powhatan, “I am ready,” to Suckahanna’s husband.

The man looked him up and down. John was dressed like a brave in a buckskin shirt and buckskin pinny. He had learned to walk without his boots and on his feet were Powhatan moccasins, though his feet would never be as hard as those of men who had run over stones and through rivers and climbed rocks barefoot since childhood. John was no longer starved thin; he was lean and hardened like a hound.

Suckahanna’s husband grinned at John. “Ready?” he asked in his own language.

“Ready,” John replied, recognizing the challenge.

But first every man had to check his weapons, and sons and girls were sent running for spare arrowheads and shafts, and new string for a bow. Then a woman ran after them with her husband’s strip of dried meat which she had forgotten to give him. It was a full hour after sunrise before the hunting party trotted out of the village. John suppressed a smug sense of satisfaction at what he regarded as inefficient delays; but kept his face grave as they jogged past the women, setting off for the fields. There were catcalls and hoots of encouragement at the men’s hard pace and at John, keeping up in the rear.

“For a white man, he can run,” a woman said fairly to Suckahanna, and Suckahanna turned her head to look after them as if to demonstrate that she had not been watching and had not noticed.

John did not permit himself a grin of satisfaction. The fat had been leached off him during his hungry time in the woods and his stay in the Indian village had been hard work. He was always running errands from field to village, or helping the women with the heavy work of clearing the land. The food they gave him had built only muscle, and he knew that though he might be thirty-five this year he had never been healthier. He imagined that Attone would think that he would drop from the line of braves panting and gasping within the first ten minutes, but he would be proved wrong.

Ten minutes went by and John was gasping for breath and fighting the desire to drop out from the line. It was not that they moved so fast, John could easily have sprinted past them, it was the very steadiness of their pace which was so exhausting. It was not a run and it was not a walk, it was a walk on the balls of their feet, a fast walk which never quite broke into a run. It was hard on the calf muscles, it was hard on the arch of the instep. It was sweating agony on the lungs and the face and the chest and the whole racking frame of the Englishman as he tried first to run and then to walk and found himself forever out of stride.

He would not give up. John thought that he might die on the trail behind the Powhatan braves, but he would not return to the village and say that he had not even sighted the deer he had promised to kill because he had been out of breath and too weary to walk to the woods.

For another ten minutes, and another unbearable ten after that, the file of braves danced along the path, following in each other’s footsteps so precisely that anybody tracking them would think he was following only one man. Behind them came John, taking two steps to their one, then one and a half, then a little burst of a run, then back to a walk.

Suddenly they halted. Attone’s fingers had spread slightly as he held his hand to his side. No other signal was needed. The fingers opened and closed twice: deer, a herd. Forefinger and little finger were raised: with a stag. Attone looked back down the line of the hunting party and slowly, one by one, all the half-shaven heads turned to look back at John. There was a polite smile on Attone’s face which was soon mirrored down the line. Here was the herd, here was a stag. It was John’s hunt. How did he propose they should go about killing one, or preferably three, deer?

John looked around. Sometimes a hunting party would set fires in the forest and drive a herd of deer into an ambush. Even more skill was required for an individual hunter to stalk an animal. Attone was famous among the People for his gift of mimicry. He could throw a deerskin over his shoulders and strap a pair of horns to his head and get so close to an animal that he could stand alongside it and all but slide a hand over its shoulders and cut its throat as it grazed. John knew he could not emulate that expertise. It would have to be a drive and then a kill.

They were near to an abandoned white settlement. Some time ago there had been a house by the river here, the deer were grazing on shoots of maize between the grass. There was a jumble of sawn timber where a house had once been and there was a landing stage where the tobacco ship would have moored. It had all gone to ruin years before. The landing stage had sunk on its wooden legs into the treacherous river mud and now made a slippery pier into the river. John looked at the lie of the land and thought, for no reason at all, of his father telling him of the causeway on the Ile de Rhé and how the French had chased the English soldiers over the island and to the wooden road across the mudflats and then picked them off as the tide swirled in.

He nodded, affecting confidence, as if he had a plan, as if he had anything in his head more than a vision of something his father had done, whereas what he needed now, and so desperately, was something he himself could do.

Attone smiled encouragingly, raised his eyebrows in a parody of interest and optimism.

He waited.

They all waited for John. It was his hunt. It was his herd of deer. They were his braves. How were they to dispose themselves?

Feeling foolish but persisting despite his sense of complete incompetence, John pointed one man to the rear of the herd, another to the other side. He made a cupping shape with his hands: they were to surround the deer and drive them forward. He pointed to the river, to the sunken pier. They were to drive the deer in that direction.

Their faces as blank as impudent schoolboys, the men nodded. Yes indeed, if that was what John wanted. They would surround the deer. No one warned John to check the direction of the wind, to think how the men would get into place in time, to disperse them in stages so that each would get to his place as the others were also ready. It was John’s hunt, he should fail in his own way, without the distraction of their help.

He had beginner’s luck. Just as the men started to move into their places the rain started, heavy thick drops which laid the scent and hid the noise of the men moving through the woodland surrounding the clearing. And they were skilled hunters and could not restrain their skill. They could not move noisily or carelessly when they were encircling a herd of deer even if they wanted to, their training was too deeply engrained. They stepped lightly on dry twigs, they moved softly through crackling shrubs, they slid past thorns which would have caught in their buckskin clouts with the sharp noise of paper tearing. They might not care whether or not they helped John in his task; but they could not deny their own skill.

In seconds the hunting team was cupped around the herd, ready for the signal to move forward. John held back, at the base of the cup, he hoped to see the herd driven before him and struggling in the mud, giving him the chance of a clear shot. He made the small gesture with his hand which meant “drive on”; and he had the pleasure of seeing all of them, even Attone, move cooperatively to his bidding.

One, two, the deer’s heads went up, the does looking for their young. The stag snuffed the wind. He could smell nothing, the wind had veered with the rain. The only scent he got was the clear water smell of the river behind the herd. Uneasily he glanced around and then he turned his head and walked a little back the way they had come, to the river.

The braves paused at John’s gesture and then, as he beckoned them, moved forward again. The herd knew that something was happening. They could see nothing in the sudden downpour of rain and hear nothing over the pitter-pat of fat raindrops on summer leaves, but they had a sense of uneasiness. They bunched closer together and followed the stag as he went, his heavy head swinging to one side and then the other, looking all about him, and led the way toward the river.

John should have held back, but he could not. He made the gesture to “go forward” and was saved from disaster only by the braves’ own skill. They could not have borne to have moved forward and stampeded the herd and lost them. Not if there had been a dozen Englishmen to humiliate. They could not have done it any more than John could have mown down a bed of budding tulips. Their skill asserted itself even over their desire for mischief. They disobeyed John’s hurried commands and fell back, waiting until the anxious heads dropped again to graze and the flickering ears ceased to swivel and flick.

John gestured again: “go forward”! And now, slowly the braves moved a little closer as if their own looming presence alone could move the deer toward the river. They were right. The empathy between deer and Powhatan was such that the deer did not need to hear, did not need to see. The stag’s head was up again and he went determinedly down the path which the farmer had once trod from his maize field to his pier, and the does and fawns followed behind.

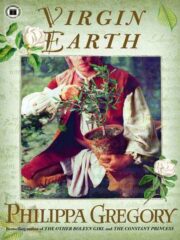

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.