“Any news?” Hester asked.

Alexander Norman nodded. “You’ve heard the news of Birmingham?”

Hester glanced toward Frances. “We won’t speak of it now. I heard enough.”

Alexander shook his head. “Dreadful doings. Prince Rupert lost control of his men altogether.”

Hester nodded. “And I heard that the king holds the whole of the west country.”

Alexander Norman nodded. “He’s lost the navy but he holds many of the ports. And they face France, so he can land a French army if the queen’s promises are fulfilled.”

Hester nodded. “And no one is marching on London?”

Alexander Norman gave a small shrug. “Not that I’ve heard, but this month alone there have been skirmishes all over the country.”

“Nothing close?”

Alexander Norman leaned forward and put his hand over Hester’s tightly gripping fingers. “Peace, cousin,” he said gently. “Nothing close. You know I would warn you the moment I heard of any danger to your little Ark. You and your precious cargo will come safe through this storm.”

He glanced over to the windowseat. “Frances, would you fetch me another glass of ale?” he asked.

She rose at once and went to the door. “And give me a moment alone with your stepmother,” he said smoothly. “I want her advice on a private matter.”

Frances glanced at Hester to see if she demurred, and when Hester gave the smallest of nods Frances slightly raised her eyebrows in a tiny expression of sheer impudent speculation and left the room, closing the door behind her.

“She’s impertinent,” Hester said as the door shut. “But it’s only lightness of spirit.”

“I know it,” Alexander Norman agreed with her. “And I would not see her subdued. She’s very like her mother. She was a lighthearted girl but her spirits were kept much in check by her strong sense of religion, and her strict upbringing. But Frances was spoiled from the moment she was born by John and by them all. It’s too late to try to weigh her down now, I would rather see her soar.”

Hester smiled. “I feel that too,” she said. “Though it falls to me to try to keep her in check.”

“You worry about her safety?”

“I do. I worry for all of us, of course, and for the treasures. But mostly for Frances. She is at an age when she should be venturing out a little more, going into society, to make friends; but she is cooped up here with me and with her brother. The plague is everywhere again this year so I cannot let her stay with her grandparents in the City – and besides they are not sociable people, they meet no one.”

“She could go to court at Oxford…”

Hester’s face was a picture. “I’d as soon throw her into the lion’s cage at the Tower than send her among that crowd. Everything that was bad about the king’s court when they were properly housed and properly served is ten times worse now they are crowded into Oxford and drunk nine nights out of ten with celebrating victories.”

“I’ve been thinking the same,” Alexander said. “I wondered if you would consider me… I wondered if you would let me offer her – and yourself of course – a safe haven. I wondered if you would leave here, shut the Ark up until the end of the war, and come and live with me at the Tower of London: the safest place in the whole of the kingdom.”

When she said nothing he added, very quietly, “I mean marriage, Hester.”

She went quite pale for a moment, and moved her chair back from his a little.

“You did not expect this? Though I have been such a frequent visitor?”

Mutely, she shook her head. “I thought it was just kindness for Mr. Tradescant’s family,” she said softly. “As a family friend, as a relation.”

“It was more.”

She shook her head. “I am a married woman,” she said. “I do not consider myself deserted or widowed. Until I hear from John that he is not coming home ever again I shall bear myself as his wife.” For a moment she looked at him as if she were pleading with him to disagree with her. “You may think he has left us forever, but I am sure he will come home. There are his children, there are the rarities, there is the garden. He would never abandon the Tradescant inheritance.”

Alexander did not answer, his face was very grave.

“He would never abandon us,” she said again but with less certainty. “Would he?”

Before he could answer she rose from the chair and went quickly over to the window with her light, determined step. “And if you are thinking that he will die over there, and never return, I must tell you that I would still think it my duty to stay here and guard the house and the garden for Johnnie to inherit when he is a man. I promised John’s father that I would keep the place and the children safe. Nothing would release me from that promise.”

“You have misunderstood me,” he burst out, “I am so sorry. I was not proposing marriage to you.”

She turned at that. The light of the window was behind her and he could not clearly see her face. “What?”

“I was thinking of Frances.”

“You were proposing marriage to Frances?”

The incredulity in her voice made him wince. Dumbly, he nodded.

“But you are fifty-five!”

“I am fifty-three.”

“And she’s a child.”

“She is a young woman, and she is ready for marriage, and these are dangerous and difficult times.”

Hester was silenced, then she turned away from him. He saw her shoulder hunch slightly, as if she were protecting herself from insult. “I beg your pardon. You must think me a complete fool.”

He took three swift steps across the room and turned her around, held her at arms’ length so that he could see her face. “I think of you, as I have long thought of you, as one of the most courageous and lovable women that I have ever met. But I know John will come home to you, and I know that you have loved him ever since you were married. I think of you now as I will always think of you, as a dear, dear friend.”

Hester looked away, wretched with embarrassment. “I thank you,” she whispered. “Please let me go.”

“It was my own shyness and stupidity in what I said that led you to misunderstand me,” he said determinedly. “Please, don’t be angry with me, or angry with yourself.”

She twisted from his hold. “I feel that I have been a fool!” she exclaimed. “Refusing a proposal which wasn’t being made to me. And you are a fool too!” She suddenly regained her spirits. “Thinking that you could marry a girl who is hardly out of her short clothes.”

He went for the door. “I’ll take a turn in the garden, if I may,” he said. “And we’ll talk again later.”

He went out without another word, and Hester, looking from the window, saw him walk along the terrace on the south side of the house and down the steps into the garden.

The garden was at its mid-May perfection. In the walled fruit garden he could not see the sky for the mass of pink and white blossoms, as thick as rose-sugared cream on a pudding. In the long walks in the flower gardens the daffodils and tulips were a wash of color, red and gold and white. The chestnut avenue was coming into its height of beauty, the blossoms opening up into thick candles, white delicately marked with pink. On the walls on the right-hand side of the garden the espaliered figs and peaches and cherries were already weighted with blossom, showering petals on the flower beds beneath them like unseasonal snow.

The parlor door behind Hester opened and Frances came in with Alexander’s glass of ale. “Has he gone?”

“You can perfectly well see that he has,” Hester snapped.

Frances put down the glass without spilling a drop and turned to examine her stepmother’s cross face.

“What did he do to upset you?” she asked calmly.

“He said something ridiculous, and I thought something ridiculous and I feel… I feel…”

“Ridiculous?” Frances suggested, and was rewarded with a glare of irritation.

Hester turned away from her and looked out of the window again. In the thick windowpane she could see, simultaneously, Alexander strolling in the garden and the reflection of her own face. She looked grim. She looked like a woman struggling under the weight of many worries, and still fighting them.

“What did he say that was so ridiculous?” Frances asked gently. She came beside her stepmother and slipped her arm around the older woman’s waist. Hester saw that smooth prettiness beside her own worn face and felt a deep pang of envy that her own beauty was past, and at the same time a glow of joy that she had brought that unloved, frightened little girl into this rare, beautiful being.

“He said that you were a young woman grown,” Hester said. She felt Frances at her side. The girl was a girl no longer, her breasts were filling out, the curve of her waist would fit a man’s hand, she had lost her coltish legginess, she was, as Alexander had seen but her stepmother had not, a young woman.

“Well, I am,” Frances said, as one stating the obvious.

“He said you should be married,” Hester said.

“And so I shall be, I suppose.”

“He thought sooner rather than later,” Hester said. “Because these are dangerous times. He thinks you should have a husband to take care of you.” She had thought that Frances would pull away and laugh her reckless laugh. But the girl rested her head on her stepmother’s shoulder and said thoughtfully: “You know, I think I would like that.”

Hester pulled back to look at Frances. “You still seem like a little girl to me.”

“But I am a young woman,” Frances pointed out. “And when I go into Lambeth the men shout at me, and call things to me. If Father were at home then it would be different, but he is not home, and he is not coming home, is he?”

Hester shook her head. “I have no news of him.”

“Then if he does not come home, and if the war goes on, and so everything is still so uneasy…”

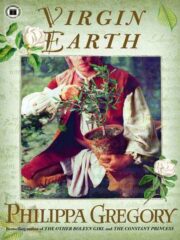

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.