“Ah,” the old woman said with pleasure at his appearance. She nodded at Suckahanna, and then tossed a buckskin cape around John’s shoulders to keep the chill of the evening air from him.

John looked around for his clothes. Everything was gone except his boots. Suckahanna was standing among a small group of women, they were all looking at his nakedness with a cheerful curiosity.

Suckahanna stepped forward and held out a bundle of clothing to him. As John took it he saw that it was a clout – a piece of cloth to twist between his buttocks and tie on a strap around his waist – a deerskin kilt and a deerskin shirt. He recoiled. “Where are my clothes?”

Suckahanna shook her head firmly. “They smelled,” she said. “And they had lice and fleas. We are a clean people. You could not wear those clothes in our houses.”

He felt ashamed and unable to argue.

“Put those on,” she said. “We are all waiting for you.”

He tied the strings of the clout around his waist and felt better with his nakedness hidden from so many bright black eyes. “Why are they all here?”

“To find the herb for your hand,” she said.

John looked down into his palm. The wound was cleaner from the sweating, but there was still a crease of rotting flesh at its center.

He pulled on the shirt and straightened the kilt. He thought that he must look absurd with his big white legs under this beautifully embroidered skirt and then his own heavy boots on his feet; but none of the women laughed. They moved off, one trotting behind another, with the old woman at the front and Suckahanna at the rear. She glanced back at John. “Follow,” was all she said.

He remembered then the unbearable steady pace she would use when they were in the woods together. All the women moved at that remorseless trot that was too fast for him to walk and too slow for him to run. He walked and then ran after them in short, breathless bursts and Suckahanna never turned her head to see if he could keep up, but just kept her own steady pace as if there were neither thorns nor stones under her light moccasins.

The old woman in the front was running and watching the plants on either side of the path. John recognized a master plants-woman when she stopped and pointed a little way into the wood. She had spotted the one she wanted, at a run, in the twilight. John peered at it. It looked like a liverwort, but a form that he had never seen before.

“Wait here,” Suckahanna ordered him and followed the other women as they went toward it. They seated themselves down in a circle around it and they were silent for a moment, as if in prayer. John felt a strange prickling on the back of his neck as if something powerful and mysterious was happening. The women held out their hands over the plant as if they were checking the heat over a cooking pot, and then their hands made weaving gestures, one to another, above and around the plant in a constant pattern. They were humming softly, and then the words of a song emerged, softly chanted.

The darkness under the trees grew more intense; John realized that the sun had set and in the upper branches of the trees there was a continual rustle and chirping and cooing of birds settling down for the night. On the forest floor the women continued to sing and then the old woman leaned forward and picked a sprig of the herb, and then the others followed suit.

John shifted restlessly from one sore foot to another. The women rose to their feet and came toward him, each chewing on the herb. John waited, in case he too had to eat it, but they walked around him in a circle. Suckahanna stopped first and gestured that he should hold out his hand. John opened his fingers and Suckahanna bent her mouth to his palm and gently spat the chewed herb into the wound. John cried out as the juice accurately hit the very center of the rotting flesh, but he could not pull his hand away because she was holding it tight. The other women pressed around him and each spat, as hard and as accurately as a London urchin, so that the chewed juice from the herb did not rest on the wound but penetrated deep inside. John yelped a little at each blow as he felt the astringent juice entering the rotting flesh. The old woman came last and John braced himself. He was right to think that her spit would be as hard as a musket ball, right into the very center of his damaged palm. As he cried out she whipped out a leather binding from the pocket of her apron, spread a leaf on top of the wound and tied it tight.

John was half-dizzy from the pain and Suckahanna ducked under his arm and supported him as they walked back to the village.

It was growing dark. The women turned off to their own huts, to the cooking fire. The men were already seated, awaiting their dinner. Suckahanna raised a hand in greeting to one of the men who solemnly watched her supporting John back to the hut. They went through the doorway entwined like lovers and she helped him lie down on the wooden bed.

“Sleep,” she said gently to him. “Tomorrow you will be better.”

“I want you,” John said, his mind hazed with pain, with the smoke, with desire. “I want you to lie with me.”

She laughed, a low amused laugh. “I am married,” she reminded him. “And you are ill. Sleep now. I shall be here in the morning.”

Spring 1643, England

On a cold day in spring, Alexander Norman took a boat upriver, disembarked north of Lambeth and strolled through the fields to the Ark. Frances, glancing idly from her bedroom window, saw the tall figure coming toward the house and dived back into her room to comb her hair, straighten her gown, and rip off her apron. She was downstairs in time to open the front door to him, and to send the maid running out into the yard to look for Hester and to tell her that Mr. Norman was come for a visit.

He smiled very kindly at her. “You look lovely,” he said simply. “Every time I see you, you have grown prettier. How old are you now? Fifteen?”

Frances cast down her eyes in her most modest gesture and wished that she could blush. She thought for a moment that she should lay claim to fifteen years, but then she remembered that a birthday invariably meant a present. “I’m fifteen in five months’ time,” she said. “October the seventh.” Without lifting her gaze, modestly directed to the toes of her boots, she could see his hand moving toward the flap on his deep coat pocket.

“I brought you these,” he said. “Some little fairings.”

They were very far from little fairings. They were three large bundles of ribbon of a deep scarlet silk shot through with gold thread. There would be enough to trim a gown and make ties for Frances’s light brown hair. Despite the shortages of the war, the fashion was still for gowns with sleeves elaborately slashed and trimmed, and Frances had a genuine need as well as a passion for ribbon.

Without taking his eyes from her absorbed face, Alexander Norman said: “You do love beautiful things, don’t you, Frances?” and was rewarded by a look of complete honesty, empty of all coquetry, when she looked up and said: “Oh, of course! Because of my grandfather! I have had beautiful things around me all my life.”

“Cousin Norman,” Hester said pleasantly, coming into the hall from the kitchen door. “What a pleasure to see you, and on such a cold day. Did you come by the river?”

“Yes,” he said. He let her help him off with his greatcoat and gave it to Frances to take to the kitchen to warm it through, and to order some hot ale. “I would not trust the roads these days.”

She shook her head. “Lambeth is quiet enough now that the archbishop’s palace is empty,” she said. “All the apprentice lads are exhausted with their drilling and their mustering and digging the fortifications. They have no stomach left for roaming around the streets and making trouble for their betters.”

She led the way into the family sitting room. Johnnie was seated before a small fire, writing out plant labels with painstaking care. “Uncle Norman!” he exclaimed and leaped up from his place. Alexander Norman greeted him with a brisk hug and then dived once again into his pocket.

“I have given your sister half a mile of silk ribbon, should you like the same to edge your suit?” he asked.

“No, sir, that is, not if you have anything else… that is, I should be very grateful for anything you bring me…”

Alexander laughed. “I have a wicked little toy here which one of the armorers made at the Tower. But you must promise me to only behead dead roses.”

From his pocket he drew a small knife that folded cunningly, like a barber’s razor, so the sharp blade was hidden and safe. “Do you permit, Mrs. Tradescant?” Alexander asked. “If he promises he will take care of his fingers?”

Hester smiled, “I should like to have the courage to say no,” she said. “You may have it, Johnnie, but Cousin Norman must show you how to handle it and see that you are safe with it before he leaves us today.”

“Can I carve things with it?”

Alexander nodded. “We’ll set to work as soon as I have drunk my ale and told your mother the news from town.”

“Wooden whistles? And toys?”

“We’ll start with something easier. Go and ask them in the kitchen for a cake of soap. We’ll work our way up to wood.” The boy nodded, put the cork carefully back in his pot of ink and carried the tray of labels out of the way, and then went from the room. Frances came in and set down a cup of ale before her uncle and then took up some sewing and sat in the windowseat. Hester, glancing across the room, thought that her stepdaughter could have been sitting for a portrait entitled “Beauty and the Domestic Arts’ as she bent her brown head over her work. A swift glance from Frances’s bright eyes warned her that the girl was perfectly aware of the enchanting picture she made.

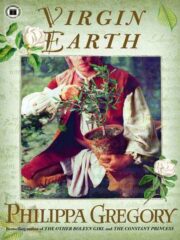

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.