He turned from the room and ran out of the door, down to the river. At the little beach before the house he knelt down to the water and plunged his hand in. The cold water felt like a blow from a whip against the damaged skin, but slowly the pain eased. “Ah God, my God,” John heard himself saying. “What a fool! What a fool I am!”

When the pain had eased a little he took his hand from the water and looked at it fearfully. The handle of the cooking pot had left a white stripe along his palm. The skin was dead-looking, swelling fast. John tried to flex his fingers; at once a sharp pain ran like a blade across his hand.

“So now I have only one good hand,” he said grimly, “and burned dinner.” He looked again at the sky. “And night coming on.”

He turned and walked slowly back up to the little house, his head full of thoughts and fears. The fire was still lit, which was one good thing. He pushed the overturned cooking pot with his booted foot. It rolled on the earth floor. It was cool, he had been down by the river for perhaps an hour. He had not known that the time was passing. He set it on its little feet and peered inside. There was nothing that he could eat. The porridge was blackened and charred almost to ashes.

John took the pot and went down to the river once more, picking his way in the twilight, which was coming on in a rush like a dark cloak thrown over the forest. He left the pot to soak in the water while he looked at his fish trap. It was empty. John went back to his pot and arduously, with his good left hand, tried to scrape out the charred remains, swill it and rinse it clean.

He filled the pot with water and, carrying it in his left hand, went back up the beach and up the little hill to his house. Where the trees had been felled before the house the forest was already regaining the land. Small vines and little weeds and ground-covering plants were invading the space. If John did not get out and dig soon the forest would crowd back in and his house would be all but forgotten, marked only on a map in the governor’s office as a headright, once claimed but then neglected, ready for another fool to take the challenge and try to make a life in the wilderness.

In the house John poured his drinking water into his cup, spilling some on the floor in his one-handed clumsiness, then he put a scoop of powdered corn flour into the water and set it to heat. This time he did not take his eyes from it, but stood over it, stirring as it thickened and came to the boil, and then set it to one side to cool before serving it into his trencher. He had made enough for breakfast tomorrow so he could eat when he woke in the morning. His stomach rumbled. He could not remember the last time he had eaten fruit or something green. He could not remember when he had last eaten meat that was not wood pigeon. He thought, absurdly and suddenly, of English plums and the sharp sweetness of their flesh. In his father’s garden there were thirty-three different varieties of plum tree, from the rare white diapered plum of Malta, which the Tradescants alone grew in all of England, to the common dark-skinned plum of every cottage garden.

He shook his head. There was no point thinking about home and the wealth his father had left him. There was no point thinking about the richness of his inheritance, the flowers, the vegetables, the herbs, the fruit. There was no point thinking about any food which he could not catch or grow in this unhelpful land. All there was for dinner tonight, and breakfast the next day, was an unappetizing mess of corn porridge. And unless he could find a way to fish and shoot with only one hand, that would be all there was for a day or so, for a week or two, until his hand healed.

With his belly full of porridge John drank water and took off his boots, ready to sleep. His cloak was missing. He looked around for it, cursing his own laziness in not hanging it up every morning. It was nowhere to be seen. John felt a disproportionate alarm. His cloak was missing, the cloak Hester had given him, the cloak he always slept in. He could feel an absurd panic rising up in him and threatening to choke him. He strode to the corner of the room where his goods were piled and turned them over, tumbling them to the ground in his haste. His cloak was not there.

“Think!” he commanded himself. “Think, you fool!”

He steadied himself and his breathing, which had become hoarse and anxious, settled down. “I must stay calm,” John said to himself, his voice quavery against the darkness. “I have left it somewhere. That’s all.”

He went through his movements. He had slept in his cloak in the afternoon and then he had run outside when the fire had burned out. He remembered then. His cloak had been tangled around his feet and he had kicked it away in his haste to get some dry wood to relight the fire.

“I left it outside,” he said quietly. “Now I’ll have to get it.”

He went slowly to the door and put his hand on the wooden latch. He paused. Through the cracks between the planks the colder night air breathed against his face like an icy sigh. It was dark beyond the wooden door, dark with a density that John had never seen before in his life, a blackness which was not challenged by firelight nor candlelight nor torchlight for dozens of miles in one direction, and hundreds, thousands, perhaps millions of miles westward. It was a darkness that was so powerful and so completely void of light that John had a foolish, superstitious fear that it he opened the door, the night would rush into the room and extinguish the fire. It was a darkness which was too great for him to challenge.

“But I want my cloak,” he said stubbornly.

Slowly, fearfully, he opened the door a little way. The clouds were thick between him and the stars, the darkness was absolute. With a little whimper John dropped to his hands and knees like a child and crawled over the threshold of his house, his hands before him feeling his way, hoping to touch his cloak.

Something brushed against his outstretched fingers and he recoiled with a sob of fright, but then he realized that it was the soft wool of his cloak. He gathered it up to him as if it was a treasure, one of the king’s most beautiful sacred tapestries. He bundled it to his face and smelled his own strong scent, not with distaste but with a sense of relief at smelling something human in this icy empty darkness.

He did not dare to turn his back on the void. With one arm tucking his cloak to his chest, he backed, still on his hands and knees, into his doorway like a frightened animal retreating into its lair, and then he shut the door.

His eyes, strained wide open against the darkness, blinked blindly when he was back in the fitful flickering light of the cottage. He shook out his cloak. It was wet with dew. John hardly cared. He wrapped himself in it and lay down to sleep. Lying on his back, his eyes still wide open in fear, he could see the steam rising off himself. If he had not been so deep in despair he would have laughed at the sight of a hungry man supping on porridge, a cold man wrapped in damp cloth, a pioneer with one hand. But none of it seemed very funny.

“Dear God, keep me safe through the night and show me what I must do in the morning,” John said as he closed his eyes.

He waited in the darkness for sleep to come, listening to the sounds of the forest outside his door. He had a moment of acute terror when he heard a pack of wolves howling in the distance, and thought that they might smell the food and come and ring the cottage with their bright yellow eyes and their lean, serene faces. But then they fell silent and John fell asleep.

When he woke in the morning it was raining. He put his cloak to one side and put the pot by the fire to heat. He stirred the porridge but when he came to eat it he found he had no appetite. He had gone through hunger into indifference. He knew he must eat; but the gray porridge, dirty with the old ash from the inside of the pot, was tasteless in his mouth. He forced himself to swallow five mouthfuls and then put the pot in the fireplace to stay warm. If there were no fish in the trap, and if he could not shoot something, then it would be porridge for dinner as well.

The stocks of wood beside the fire were low. John went outside. The woodpile was low too and damp from the rain. John took nearly all of it and stacked it inside the house to dry. He went to grasp his ax to go and cut some more but the pain from his burned hand made him cry out. He could not use the ax until the burn was healed. He would have to gather wood, break up what he could by stamping on it, and burn the longer branches from one end to another, pushing them into the heart of the fire as they were consumed.

He went out into the rain, his head bowed, wearing only his homespun coat, leaving his cloak behind to dry. He had seen a fallen tree rather like an oak when he had been out with his gun a few days ago. He trudged toward it. When he got there he saw that some of the branches had split from the main trunk. There was wood that he could use. Using only his left hand, he pulled a branch away from the rest of the tree, and tucked the limb under his arm. It was hard work getting it home. The broad sweep of the branch kept getting caught in the undergrowth, wedged against trees, enwrapped in ground vines. Again and again John had to stop and go back and break it free. The forest of John’s headright was thick, almost impenetrable, it took John all the morning to travel just one mile with his firewood, and then another hour to break it up into manageable logs before bringing it inside the house to dry.

He was soaked through by the rain and by sweat and aching with tiredness. The burn on his hand was oozing some kind of liquid. John looked at it fearfully. If the wound went bad then he would have to go to Jamestown and put himself in the hands of whatever barber surgeon had set up in the town. John was afraid of losing his hand, afraid of the journey to Jamestown, one-handed in a dugout canoe, but equally afraid of staying on his own in the cottage if he became ill. He could taste the sweat on his upper lip and recognized the scent of his own fear.

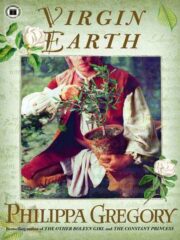

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.