John pushed away from the tree but found that his legs could hardly support him. His sense of loneliness and fear had weakened him. He staggered back toward his house and thanked God there was at least a curl of smoke coming from the chimney, and suppawn in the cooking pot. John felt his throat close at the thought of eating cold porridge again. He fell to his hands and knees and retched. “God, my God,” he said.

A little saliva dribbled from his mouth. He wiped it on his sleeve. The strong brown homespun of the sleeve was stinking. He noticed it when he brought it to his face. “My clothes smell,” he said in quiet surprise. “I must smell.”

He touched his hand to his face. His beard had grown and was matted and dirty, the mustache was long around his mouth. “My breath must smell, I am filthy,” he said softly. “I am so foul that I cannot even smell myself.” He felt humiliated at the knowledge. John Tradescant, the apple of his mother’s eye, his father’s only heir, had become a dirty, bedraggled vagrant, clinging to the edge of the known world.

He dragged himself to his feet again. The sky seemed to look down on him as if he were a tiny, tiny insect making its arduous way across a massive leaf on a tree in a forest in a country that was too great for any man to cross.

John stumbled to his door and pushed it open. Only in the cramped room could he restore his sense of scale. “I’m a man,” he said to the four rough wood walls. “Not a tiny beetle. I am a man. This is my house.”

He looked around as if he had never seen it before. The four walls had been made of newly felled green wood, and as the fire heated the room and the weather warmed, the wood had shrunk. John would have to take clay and twigs to patch the gaps. He shuddered at the glimpse of the forest through the cracks of the house walls, as if the wildness outside was seeping in through his house to attack him.

“I can’t,” he said miserably. “I can’t build the house and find food and wash and hunt and clear the land as well. I can’t do it. I’ve been here for nearly two months, and all I can do is survive, and I can barely do that.” His throat closed again and he thought he was going to retch but instead he spat out a hoarse sob.

He felt the waistband of his trousers. He had thought that, for some reason, his belt had been stretching but now he realized that he was thinner. “I’m not surviving,” he finally acknowledged to himself. “I’m not getting enough to eat.”

At once the tiredness which was now familiar, and the ache in his belly which he had thought was some kind of mild illness, made a new and terrifying sense. He had been hungry for weeks and his hunger was making him less and less competent to survive. He missed his shot more and more often, his stock of logs for the fire was harder to cut every day. He had fallen back on gathering firewood rather than making the effort of swinging an ax. This meant that the wood was drier and burned quicker so that he needed more, and it also meant that the land around the little house was no clearer than it had been when Bertram had come over to help him build his house at the start of their time in the wilderness when they had been confident and laughing.

“Spring is here and I have planted nothing,” John said dully, holding a fold of his waistband in his calloused hand. “The ground is not clear, and I cannot dig. I have no time to dig. Just getting in food and water and fuel takes all my time, and I am tired… I am so tired.”

He stretched out his hand for his cloak. It was not folded tidily away in the corner of the room any more but left in the corner where he kicked it to one side in the mornings. He wrapped himself in its thick warmth. Hester had bought it for him when he said that he was going away, he remembered. Hester, who had not wanted to come. Hester, who had sworn that the new country was not for men and women who were used to the ease and comfort of town life, that it would suit only farmers who had no chance of doing well in their home country, farmers and adventurers and risk takers who had nothing to lose.

John lay down on the bare earth floor before the glow of the fire and pulled the collar of the cloak up over his face. Although it was morning he felt he wanted to pull the cloak over his head and let himself sleep. He heard a small, pitiful sound, like Frances used to make when she woke from a bad dream in the night, and realized that it was himself, and that he was weeping like a frightened child. The little sound went on, John heard it as if he were far away from his own fear and weakness, and then he fell asleep, still hearing it.

He woke feeling hungry and afraid. The fire was nearly out. At the sight of the gray ash in the grate John leaped to his feet with a gasp of fear and looked out of the open window. Thank God, it was not dark, he had not slept away the whole day. He stumbled outside, the cloak clinging to his feet, making him stumble, and gathered armfuls of wood from his outside store. He tumbled the logs into the grate and prised off the dry pieces of bark. With little twigs he poked the bark into the heart of the red embers and put his head down into the ash and blew, gently, softly, praying that they would catch. It took a long time. John heard himself muttering a prayer. A little flame flickered yellow like a candle, and then went out.

“Please God!” John breathed.

The little flame flickered yellow again and caught. The twist of bark crisped, burned, and was consumed. John laid a couple of twigs across it and was rewarded by them catching alight at once. Immediately he fed the fire with bigger and bigger twigs until it was burning brightly and John was safe from the coming darkness and cold once more.

He realized then that he was hungry. In his cooking pot was porridge from last night, or if he wished to give himself the labor he could clean out the pot and set some water to boil and try to shoot a bird for meat. There was nothing else to eat.

He put the cooking pot a little closer to the flames so that the porridge would not be stone cold, and went to the door.

The evening was drawing in. The sun had gone behind the trees and the sky above the little house was veiled with strips of thinnest cloud, like the shawl the queen used to wear over her hair when she was on her way to Mass. “Mantilla clouds,” John said, looking up at them. The sky was pale, the color of dead lavender heads in winter, the color of heather in summer, violet and pink with all the brightness drained away.

John shivered. His momentary admiration of the sky had suddenly changed. At once it looked again too vast, too indifferent, it was impossible that a man as small as him could survive under the great dome of it. From the mantilla clouds looking down, John’s home would be nothing more than a little speck, John peeping out would be smaller than a flea. The country was too big for him, the forest too wide, the river too rich and cold and fast-flowing and deep. John had a sense that all his new life was nothing more than an arduous crawling like a little ant from one place to another and that his survival was of no interest to the sky, any more than the life of an ant was of interest to him.

“God is with me,” John said, summoning Jane’s faith.

There was a silence. There was no sign that God was with him. There was no sign that there was any God. John remembered Suckahanna casting smoking tobacco on the river at sunrise and sunset, and thought for a blasphemous moment that perhaps this land had strange gods, different gods, from England; and that if John could somehow creep under the protection of the gods of the new world then he would be safe from the indifferent gaze of the swelling sky.

“I should be praying,” John said quietly. He did not observe Sundays here in the wilderness. He did not even pray before his meals nor before he lay down to sleep at night. “I don’t even know when Sunday is!” John exclaimed.

He could feel panic rising up in him at the thought that he had slept during this day; but he did not know how long he had slept. He did not know how far the town was downriver, how long it would take him to get there, that he did not even know what day it was.

“I cannot go into town dressed like this and stinking like an animal!” John said. But then he stopped. How was he to get clean if not in town? He could hardly wash and dry the clothes he needed unless he was prepared to run as naked as a savage in the forest. And how could he pay for all his laundry to be done in the town like some fine gentleman? All his money should be spent on hiring laborers to clear his land, buying seed corn, buying tobacco seeds, new axes, more spades.

John thought of the wealth of the house at Lambeth. He thought of the servants who did the work for him: the cook who prepared the meals, the maid who waited in the house, the garden and the gardeners, his wife Hester who ordered it all done; and how he had wildly, madly decided that none of it was for him any longer, and that his life belonged somewhere else, with another woman. Now he looked ready to die in that somewhere else. And the other woman was lost to him.

“That is all this place is to me,” he said softly. “Somewhere else. I am living in somewhere else and I am going to die in somewhere else unless I can get myself home again.”

A sharp, acrid scent reminded him abruptly of his dinner. He turned with a cry of distress. The cooking pot was spewing a dark smoke into the room, it had overheated and the porridge had stuck to the bottom of the pot and was burned.

John lunged to pull it away from the fire and then recoiled as the hot metal handle scorched into his hand. He dropped the pot and cursed, his hand burning with pain. He had a little water left in his cup and he poured it over the burn. The skin puckered up and turned white. John felt the sweat break out on his face at the pain and he cried out again.

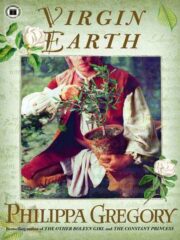

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.