John looked out of the open slit of the window at the iron-gray sky and the falling snow and thought of Suckahanna, barefoot in the frozen woods where the snow was dozens of feet deep and the wolves howled at night. “How could anyone survive out there in winter?”

Hobert shook his head. “Nobody can,” he said.

Winter 1642-43, Virginia

Bertram Hobert rented lodgings in town for himself, his wife, Sarah, and his slave, a black man called Francis. After John complained of the treatment he got at the inn, Hobert said he could stay with them until the spring, and then the whole party would go upriver to look at their new land.

John found the town much changed. A new governor, Sir William Berkeley, had arrived from England and had equipped the official residence with beautiful furniture and goods. His wife, who was already a byword in the community for her looks, was giving parties and all those who could remotely pass as a gentleman and his lady were dressing in their best and walking up the drive to the governor’s house. The roads were paved now, and the tobacco was no longer grown at the street corners and on any corner of spare land. A man could buy or sell using coin and not pinches of tobacco or bills drawn on a tobacco merchant’s. “It’s become a town and not a camp,” John remarked.

Those were the beneficial changes of the four years. There were others that filled him with worry for Suckahanna and her mother. The river was now lined with plantations from its mouth right up to James’s Island. Before each of the planters’ houses the land had been cleared and the fields stretched down to the little wooden piers and quays. On James’s Island itself the fields ran into each other, there was no forest left at all. On the more distant banks the land was black where it had been burned and not yet plowed. John could not see how Suckahanna and her people could survive in a country which was turning itself into fields and houses. The woods she had roamed every day for mile after mile, hunting turkey or wood pigeon, or looking for roots or nuts, were burned back to a few scorched trees among plowed fields. Even the river, where she had followed the schools of fish ready to catch them wherever the flow of the water was right, was enclosed by riverfront acres and penetrated by landing piers.

John thought he might be imagining it – or perhaps it was the effect of the freezing-cold weather – but it seemed to him that the flocks of birds were fewer, and he no longer heard the wolves howling outside the walls of Jamestown. The countryside was being tamed, and the wild animals and the people who lived alongside them were being driven inland and away. John thought that if Suckahanna was with her people they might have been driven far away to where the burgesses’ map showed nothing more than a space marked “forest.” He started to fear that he would never find her again.

Bertram busied himself with trade while they were waiting for the weather to change. Since it was his second visit to Jamestown, he had judged his market well. He had brought a store of the little European luxuries that the colonists missed so much. Most afternoons he was welcomed in the better homes to show his supplies of paper and ink, pens and soap, real candles, rather than the green wax of the Virginian candleberries, French brandy rather than the eternal West Indies rum, lace, cotton, linen, silk, anything carved with skill or made with artistry that reminded the colonists of home where skill and artistry had been easily hired.

John went with him on these visits and met a new sort of people, people for whom the old divisions of gentry and laborers no longer applied, for they all labored. What mattered now was the gradation of skills. A clever carpenter or an able huntsman was more respected in this new country than a man with a French surname or knowledge of Latin. A woman who could fire a musket and skin a deer was her husband’s helpmeet and partner, and more valuable to him than if she could write poetry or paint a landscape. Hester would have thrived in this place where a woman was expected to work as hard as a man, and to take her own share of responsibilities, and every day John found himself wishing that she had come with him, and, contradictorily, longing for news of Suckahanna.

Sarah Hobert reminded John of Hester. She prayed every morning, and said grace at every meal, and in the evenings she taught Francis the slave his letters and the catechism. When John saw her with a chicken over her knees plucking and saving the feathers for a pillow, or scraping cobs of corn by the fireside in the evening, and then carefully setting the empty cobs in the woodbasket for fuel, he remembered Hester: hardworking, conscientious, and with an inner strength and silence.

For a while he thought the cold weather would never lift and free them from the idle life of Jamestown, but Hobert swore he would not go upriver while the snow was still thick on the ground. “A man could die out there and no one ever know, and no one ever care,” he said. “We stay in town until the ground warms up and until we can row upriver without great bergs of ice crashing down around us. I won’t take the risk of moving from the town until spring.”

“And then it would be more dangerous to stay,” his wife said quietly. “They have terrible fevers here in the hot weather, Mr. Hobert. I would rather be well away from here before the summer comes.”

“In good time,” he said with a glance at her under his eyebrows which warned her to hold her peace and not join in with the councils of men.

“In God’s time,” she said pleasantly, not the least overawed.

John knew that Hobert was right but still he felt impatient. He asked all the townspeople he met if they remembered the girl or her mother, but people told him that one Indian looked like another, and if the girl had vanished then no doubt she had been stealing or betraying her master and had run off to the woods to her own people.

“And precious comfort she’ll get there,” one woman told him as she waited by the town’s only deep well for her turn to draw water.

“Why?” John asked urgently. “What d’you mean?”

“Because every day they get pushed back a little more. Not now in the winter, because our men don’t go out into the woods in winter, it gets dark too early and the cold can kill a man quicker than an arrow. But when spring comes we will make up packs of dogs and bands of hunters and go hunting the redskins, we force them back and back and back, so the land is clear for us and safe for us.”

“But she’s only a girl,” John exclaimed. “And her mother a woman all alone.”

“They would breed if left alone,” the woman said with stout indifference. “I don’t mean to shock you, mister, but it’s us or them on this land. And we’re determined that we shall be the victors. Whether it’s wolves or bears or Indians, they have to fall back and give way before us or die. How else can we make this land our own?”

It was a ruthless logic that John could hardly condemn, for he himself held four headrights of riverside land and virgin forest and he heard himself talking with anticipation of the trees he would clear and the house he would build, and he knew that his own land was another two hundred acres where the Powhatan would never hunt again.

April 1643

He had to wait until April, and then he and the Hoberts rowed upriver and saw their adjoining plots. It was good land. The trees reached down to the water’s edge and their thick canopy shaded the banks. Their wide gray roots stretched out into the flooded river. John tied the canoe he had borrowed to an overhanging trunk and stepped ashore on his own new land.

“My Eden,” John said quietly to himself.

The trees were alive with the singing of birds, birds courting and chasing, fighting and nesting. He saw birds that looked like familiar English species but which were bigger, or oddly colored, and he saw others that were wholly new to him in this new and wonderful world, birds like little herons which were white as doves, strange ducks with heads as bright as enameled boxes. The soil was rich, dark and fertile, an earth which had never known the plow but which had made and remade itself with centuries of tumbling leaves and rotting vegetation. Feeling almost foolish, John went down on his hands and knees, took a handful of the rich soil, crumbled it between his hands and raised it to his nose and his lips. It was good dark earth that would grow anything in rich abundance.

The bank sloped steeply up from the river, there would be no flooding on his fields, and there was a little hillock, perhaps half a mile back from the river frontage, where John would build his house. When the trees were cleared he would have a fine river view, and he would be able to look down the hill to his own landing stage where his own tobacco would be loaded to take downstream.

John thought his house would be set square to the river. A modest house, nothing like the grand size of Lambeth: a pioneer’s house of one room downstairs and a ladder leading up to a half floor for storage set in the eaves. A fireplace in one wall, which would heat the whole of the little building, a roof of reeds or maybe even wooden shingles. A floor of nothing more than beaten earth in the first few years, perhaps later John would put down floorboards. Windows which would be bare and open, empty of glass, but with thick wooden shutters to close in winter and bad weather. It would be a house only a little grander than an English pauper might build to squat on common land and think himself lucky. It would be a normal house in this new world, where nothing could be taken for granted and where men and women rarely had anything more than they could build or make for themselves.

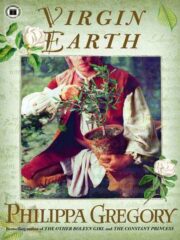

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.