Great ditches are dug outside London against the coming of a French or Spanish army and all of our gardeners have to go and take their turn with the digging whether they will or no.

Food is scarce because the markets are closed as country people will not travel from their homes, and carters are afraid of meeting armies on the roads. I am feeding vagrants at the door with what we can afford but we are all doing very poorly. All the dried and bottled fruit is finished and I cannot get hold of hams to salt down for love nor money.

These are strange and difficult times and I wish you could be with us. I am keeping up my courage and I am caring for your children as if they were mine own, and your rarities and gardens also are safe.

I trust you will come home as soon as you are released from service.

God be with you,

Your wife,

Hester Tradescant

John turned Hester’s letter over in his hands. He had an odd, foolish thought that if she were not his wife already, he would admire and like this woman more than any other he knew. She cared for the things that mattered most to him as if they were her own. It was a great comfort to him to know that she was in his house, in his father’s house, and that his children and his rarities and his garden were under her protection. He felt an unexpected tenderness toward the woman who could write of the difficulty of the times and yet assure him that she was keeping up her courage. He knew he would never love her as he had loved Jane. He thought he would never love another woman again. But he could not help but like and admire a woman who could take control of a household as she had done, and confront the times that they lived in as she did.

John rose to his feet, picked hay off his doublet, and went to his dinner in the great hall of York castle.

The king and his noble friends, splendidly dressed, were already in their place at the top table as John slipped into the hall. They were dining off gold plate but there were only a dozen dishes. The county was finding it hard to feed the appetite of the court, the provincial cooks could not devise the dishes that Charles expected, and the farms and markets were drained by the hunger of the enlarging, idle, greedy court.

“What news?” John asked, seating himself beside a captain of the guard and helping himself from the shared dish placed in the middle of the table.

The man looked at him sourly. “None,” he said. “His Majesty writes letters to all who should be here, but the men who are loyal are already here, and the traitors merely gain the time to make themselves ready. We should march on London now! Why give them more time to prepare? We should put them to the sword and cut out this canker from the country.”

John nodded, saying nothing, and bent over his meat and bread. It was venison in a rich, dark sauce, very good. But the bread was coarse and brown with gritty seeds. The rich wheat stores of Yorkshire were slowly emptying.

“While he is waiting I might go to my home,” John said thoughtfully.

“Lambeth?” the captain asked.

John nodded.

“You’d be seen as a traitor,” the man said. “London is solid against the king, you’d be seen as a turncoat. You’d never plant another bulb for him.”

John grimaced. “I’m doing next to nothing here.”

The man spat a piece of gristle on the rushes of the floor and one of the dogs squirmed forward on its belly to lick it up. “We’re all doing next to nothing here,” he said. “Nothing but waiting. It is war. All that is undecided is when and where.”

July 1642

All that spring and summer the country was waiting, like the captain, to see when and where. Every gentleman who could command men to follow him armed them, drilled them and trained them, and then wrestled with his conscience night and day as to which side he should join. Brothers from the same great house might take opposite sides and divide the tenants and servants amongst them. The men of one village might come out as passionate royalists, the men of the village next door might side with Parliament. Local loyalties set their own traditions: Villagers in the shadow of a great courtier’s house that had felt the benefits of royal visits might sharpen their pikes and put a feather in their hat for the king. But villagers along roads from London where the news was easily spread, knew of the king’s evasions and lies before the demands of Parliament. Those who prized their freedom of conscience, or those who were prosperous, free-thinking men, said that they would leave their work and their homes and take up the sword and fight against papacy, superstition and a king who was driven to sin by his bad advisers. Those whose habits of loyalty had gone deep with Elizabeth and deeper with James, and were far from the news of London, would turn out for the king.

In early July, as the court at York started to complain of the smell of drains and to fear the plague in the overcrowded town, the king announced that they were to march to Hull once again. This time the plan was better laid. The royalist George Digby was inside the garrison and he had forged a plan with Hotham the governor that the town would open its gates to a besieging force from the king, as long as the force was sufficiently impressive to justify a surrender.

Charles himself, dressed in green as for a picnic, rode out at the head of a handsome army on a warm summer day in early July. Tradescant rode at the tail end of the courtiers, and felt that he was the only man in the chattering, singing, lighthearted band who wished that he was elsewhere, and who doubted what they were about to do.

The city’s defenders were bolstered by soldiers sent by the Scots. “It makes no difference, we have an agreement,” Charles said contentedly.

The foot soldiers laid aside their pikes and got out spades. The royal army started to dig a ring of trenches around the city. “They will surrender before we are more than a foot deep,” Charles assured his commanders. “No need to dig the lines t-too straight or too well. If they do not surrender t-tonight, we will attack at dawn tomorrow. As long as we make a sh-show.”

As the soldiers dug their trenches, and as Charles broke his fast with some red wine and bread and cheese, a simple meal, as if he were out on a hunting trip, the great gates of Hull slowly opened.

“Already?” Charles laughed. “Well, this is gracious!” He shaded his eyes with his hand, and then shook his head and stared harder. The bread fell from his hand, unregarded. Slowly, his laughter died.

A regular well-drilled army marched steadily out from the gates of the town toward them. The front flank kneeled down and the musketmen, steadying their weapons on the shoulders of the front rank, took aim and fired straight at the royalist army.

“Good G-God! What are they doing?” Charles cried.

“To horse!” one of the quicker courtiers shouted. “Get the men saddled up! We’ve been betrayed!”

“It can’t b-be…”

“Save the king!” Tradescant shouted. The royal guard, recalled to their duties, dropped their dinner in the dust and threw themselves on their horses.

“Mount! Your Highness!”

There was a dreadful scream as another volley of shots pocked the dry ground around them, and some of the musket balls found a target.

“Retreat! Retreat!” someone yelled.

All the orders of command were broken, as the men scattered, running like panicked sheep across the stubbly hayfields, pushing through hedges and trampling down the ripening corn. Still the defenders of Hull came forward, the first rank dropping to their knees and reloading as the second rank fired over their shoulders and then marched on. Then they too dropped down and reloaded as the men behind them fired.

It was an unstoppable progress, John thought. The king’s soldiers did not even have fire lit ready for their muskets. They had no cannon ready, they did not even have their pikes. All they had were their trenching spades, and the men who had been digging had been the first to fall, toppling down into their shallow ditches, and screaming and crawling in the dirt.

At last someone found a trumpeter and ordered him to sound the retreat, but the foot soldiers were already up and running, running from the well-disciplined lethal ranks that were pouring, like little toy soldiers, out of the gates of Hull, firing and reloading, firing and reloading, like a monstrous toy which could not be stopped or escaped.

The king’s guards surrounded his horse and galloped him away from the battle. Tradescant, his own horse snorting and pulling, looked wildly around him and then followed the king. His last view of the battlefield was a horse, its stomach blown open by a cannon shot from the walls of the city, and a lad, not much more than fourteen, trying to shelter behind the body.

“This is the end,” John found he was saying as his horse wearily found the road to York and followed in the train of the ragged retreat. “This is the end. This is the end. This is the end.”

August 1642

For the king it was the beginning. The second humiliation outside the walls of Hull had decided him. The queen’s continual demands that he confront and defeat his parliament drove him on. He issued a proclamation that every able-bodied man in the country should rally to his army, and on Eastcroft Common outside Nottingham he paraded three cavalry troops and a battalion of infantry while the herald read the proclamation of war. John, standing behind his master in the pouring rain, thought that never in the history of warfare did any campaign look less promising.

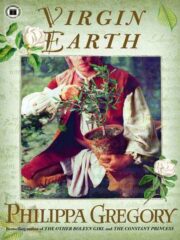

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.