“She wants me to take Hull,” the king said stubbornly. “And it is mine own. I am claiming nothing but what is mine by right.”

Tradescant bowed. When the king started speaking of his rights it was difficult to make any headway. By right everything in the four kingdoms was his; but in practice the countries were ruled by all sorts of compromises. Once the king assumed the voice he used in his masques and spoke grandly of his rights nothing could be agreed.

“When do we go to Hull?” John asked resignedly.

The king smiled at him, a flash of the old merriment in his eyes. “I shall send the P-prince James in to Hull on a visit,” he said. “They cannot refuse a visit from the prince. He shall g-go with his cousin, the Elector Palatine. And then I shall f… follow him. They cannot separate father and son. And once he is inside he will open the gates to me. And once I am there” – he snapped his fingers – “it is mine! As easily and peacefully as that.”

“But what if…”

The king shook his head. “No. N-no carping, Tradescant,” he said. “The city of Hull is all for me, they will throw open the gates at the sight of Prince James, and then, when we are installed, we can make what terms we wish with Parliament.”

“But Your Majesty…”

“You may go now,” the king said pleasantly. “Ride with me at n-noon tomorrow to Hull.”

They left late, of course, and idled along the road. By the time they finally arrived on a little rise before the town it was getting cold with the sharp coldness of a northern spring afternoon, and growing dark, getting on for dinner time. The king had brought thirty cavalrymen, carrying his standards and pennants, and there were ten young gentlemen riding with him as well as Tradescant and a dozen servants.

As they came toward the city Tradescant saw the great gates swing closed, and his heart sank.

“What’s this?” the king demanded.

“A damned insult!” one of the young men cried out. “Let’s ride at the gates and order them open.”

“Your Majesty…” Tradescant said, bringing his horse a little closer. The young courtiers scowled at the gardener riding among them. Tradescant pressed on. “Perhaps we should ride by, as if we never intended coming in at all.”

“What use would that be?” the king demanded.

“That way, no one could ever say that an English town closed its gates to you. It did not close its gates because we were not trying to enter.”

“Nonsense!” the king said easily. One or two of the young men laughed aloud. “That’s the way to teach them b-boldness. Prince James’s party will open the gates to us if the governor of Hull does not.”

The king took off his hat and rode down toward the town. The sentries on the wall looked down on him and John saw, with a sense of leaden nausea, that they were casually pointing their crossbows toward him, their monarch, as if he were an ordinary highwayman coming toward the city walls.

“Please, God, no fool fires by accident,” John said as he followed.

“Open the gates to the king of England!” one of the courtiers shouted up at the sentries.

There was a short undignified scuffle and the governor of Hull, Sir John Hotham himself, appeared on the walls.

“Your Majesty!” he exclaimed. “I wish we had known of your coming.”

Charles smiled up at him. “It does not m-matter, Sir John,” he said. “Open the gates and let us in.”

“I cannot, Your Majesty,” Sir John said apologetically. “You are too many for my little town to house.”

“We don’t m-mind,” the king said. “Open the gates, I would see my son.”

“There are too many of you, it is too large and too warlike a party for me to let in at this late hour,” Sir John said.

“We are not warlike!” Charles exclaimed. “Just a small party of pleasure-seekers.”

“You are armed,” the governor pointed out.

“Only my usual g-guards,” the king said. He was still smiling but John could see the whiteness around his mouth and his hand trembling slightly on the reins. His horse shifted uneasily. The royal guards stared, stony-faced, at the sentries on the towers of Hull.

“Please, Your Majesty,” Sir John Hotham pleaded. “Enter as a friend if you must enter. Bring in just a few of your men if you come peacefully.”

“This is my t-town!” the king shouted. “Do you… do you… do you deny your king the right to enter his own town?”

Sir John closed his eyes. Even from the road before the gate the king’s party could see his grimace. John felt a deep sense of sympathy for the man, torn between loyalties just like himself, just like every man in the kingdom.

“I do not deny Your Majesty the right to enter into your town,” the governor said carefully. “But I do deny these men the right to enter.” His gesture took in the thirty guards. “Bring in a dozen to guard Your Majesty and you shall dine with the prince in the great chamber this night! I shall be proud to welcome you.”

One of the courtiers edged his horse up to the king. “Where is the prince’s party?” he said. “They should have thrown open the gates to us by now.”

Charles shot him an angry look. “Where indeed?” He turned back to the governor of Hull. “Where is m-my son? Where is Prince James?”

“He is at his dinner,” the governor said.

“Send for him!”

“Your Majesty, I cannot. I have been told he is not to be disturbed.”

Charles spurred his horse abruptly forward. “Have d-d-done with this!” he shouted up at the governor. “Open the gates! That is an order from your k-king!”

The man looked down. His white face had gone paler still. “I may not open the gates to thirty armed men,” he said steadily. “I have my orders. As my king you are always welcome. But I do not open the gates of my town to any army.”

One of the king’s courtiers rode forward and shouted at the people whose curious faces were peering over the tops of the defensive walls. “This is the king of England! Throw your governor down! He is a traitor! You must obey the king of England!”

No one moved, then a surly voice shouted, “Aye, and he’s the king of Scotland and Ireland too and what justice do they have there?”

The king’s great horse reared and shied as he pulled it back. “Then b-be damned to you!” the king shouted. “I shall not forget this, John Hotham! I shall n-not forget that you locked me out of my own town!”

He wheeled the horse around and flung it into a gallop down the road, the guards thundering behind him, the courtiers, servants and John with them. He did not pull up till his horse was blown and then they turned and looked back down the road. In the distance they could see the gates finally open, the drawbridge come down, and a small party of horsemen ride out, following in their tracks.

“Prince James,” the king said. “Ten minutes too l-late.”

The king’s party waited while the horsemen rode nearer and nearer and then pulled up.

“Where the devil were you, sir?” the king demanded of his nephew, the Elector Palatine, who had led the party.

“I am sorry, Your Majesty,” the young man replied stolidly. “We were at our dinner and did not know you were outside the gates until Sir John came to us just now and said you had ridden away.”

“You were supposed to open the g-gates to me! Not idle with your no-noses in the trough!”

“We were not sure you were coming. You were due before dinner. You said you would come in the afternoon. We gave up waiting for you. I thought the governor would have opened the gates to you himself.”

“But he refused! And there was no one to force him, b-b-because you were at your dinner, as usual!”

“I’m sorry, Uncle,” the young man replied.

“You will be sorrier yet!” the king said. “For now I have been refused admittance to one of my t-t-towns as well as being banned from my City! You have done evil, evil work this day!” He turned on his son. “And you, J-James! Did you not know that your father was outside the gates?”

The prince was only eight years old. “No, sire,” he said. His little voice was scarcely more than a thread in the cold evening air.

“You have disappointed your f-father very much this day,” Charles said gloomily. “Pray to G-God that we have not taught disloyal and wicked men the lesson that they can defy me and travel in their w… wicked ways and fear nothing.”

The prince’s lower lip trembled slightly. “I didn’t know. I am sorry, sir. I didn’t understand.”

“It was a harebrained plan from first to last,” the Elector said dourly. “Whose was it? Any fool could see that it would not work.”

“It was m-my plan,” the king said. “But it required speed and decisiveness and c-courage, and so it failed. How am I to succeed with such servants?” He surveyed them as if they were all equally to blame, then he turned his horse’s head toward York and led them back to the city through the darkening twilight.

April 1642

When they got back to York John found a letter waiting for him from Hester. It had taken nearly a month to reach him instead of the usual few days. John, looking at the dirt-stained paper, realized that, along with loyalty and peace, everything else was breaking down too: the passage of letters, the enforcement of laws, the safety of the roads. He went to his pallet bed in the hayloft and sat where a crack in the shingles of the roof let in the cold spring light and he could see to read.

Dear Husband,

I am sorry that you have gone away with the court and I understand that it was not possible for you to come and say farewell before you rode away. I have hidden the finest of the rarities where we agreed, and sent others into store at the Hurtes’ warehouse where they have armed guards.

The city is much disturbed. Every day there is drilling and marching and preparations for war. All the apprentice boys in Lambeth have given up their rioting around the streets and are now formed into trained bands and drilled every evening.

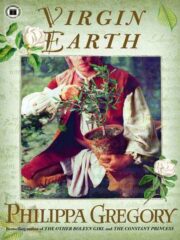

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.