“And pretty flowers,” the queen added. “White and blue flowers in the knot garden.”

John bowed his assent, keeping his face hidden. White and blue were the flowers of the Virgin Mary. The queen was asking for a Papist knot garden on the very edge of a London on the brink of revolt.

“We need somewhere to retire in these troubled times,” the king said. “A little hidden garden, Tradescant. Somewhere that we can b-be ourselves.”

The queen stepped to one side to look at a neglected watercourse, lifting her silk dress carefully away from the wet ground.

“I understand,” John said. “Will you be here only in summer, Your Majesty? It helps me if I know. If you are not to be here in autumn then I do not need to plant for that season.”

“Yes,” the king said. “A summertime p-place.”

John nodded and waited for further orders.

“It pleases me to give her a p-pretty little h-house of her own,” the king said, watching the queen at the end of the little terrace. “I have great work to do – I have to d-d-defend my crown against wild and wicked men who w-would pull me down, I have to d-defend the church against Levelers and s… and s… and sectaries and Independents who would unstitch the very fabric of the country. It is all for m-me to do. Only I can preserve the country from the m-madness of a few wicked men. Whatever it costs me, I have t-to do it.”

John knew he should say nothing; but there was such a strange mixture of certainty and self-dramatization in the king’s voice that he could not remain silent. “Are you sure that you have to do it all?” he asked quietly. “I know some sectaries, and they are quiet men, content to leave the Church alone, provided that they can pray their own way. And surely, no one in the country wants to harm you or the queen, or the princes.”

Charles looked tragic. “They d-do,” he said simply. “They drive themselves on and on, c-caring nothing for my good, c-caring nothing for the country. They want to see me cut down, cut down to the size of a little p-prince, like the d-doge of Venice or some cat’s-paw of Parliament. They want to see the p-power my father gave me, which his aunt g-gave him, cut down to n-nothing. When was this country t-truly great? Under King Henry, Queen Elizabeth and my f-father, King James. But they do not remember this. They don’t w-want to. I shall have to fight them as traitors. It is a b-battle to the death.”

The queen had heard the king’s raised voice and came over. “Husband?” she inquired.

He turned at once, and Tradescant was relieved that she had come to soothe the king.

“I was saying how these m-madmen in Parliament will not be finished until they have destroyed my ch-church and destroyed my power,” he said.

John waited for the queen to reassure him that nothing so bad was being plotted. He hoped that she would remind him that the king and queen he most admired – his father, James, and his great-aunt Elizabeth, had spent all their lives weaving compromises and twisting out agreements. Both of them had been faced with argumentative parliaments and both of them had put all their power and all their charm into turning agreements to their own desire, dividing the opposition, seducing their enemies. Neither of them would ever have been at loggerheads with a force that commanded any power in the country. Both of them would have waited and undermined an enemy.

“We must destroy them,” the queen said flatly. “Before they destroy us and destroy the country. We must gain and then keep control of the Parliament, of the army and of the Church. There can be no agreement until they acknowledge that Church, army, and Parliament is all ours. And we will never compromise on that, will we, my love? You will never concede anything!”

He took her hand and kissed it as if she had given him the most sage and levelheaded counsel. “You see how I am advised?” he asked with a smile to Tradescant. “You see how w-wise and stern she is? This is a worthy successor to Queen Elizabeth, is sh-she not? A woman who could defeat the Sp-Spanish Armada again.”

“But these are not the Spanish,” John pointed out. He could almost hear Hester ordering him to be silent while he took the risk and spoke. “These are Englishmen, following their consciences. These are your own people – not a foreign enemy.”

“They are traitors!” the queen snapped. “And thus they are worse than the Spanish, who might be our enemies but at least are faithful to their king. A man who is a traitor is like a dog who is mad. He should be struck down and killed without a second’s thought.”

The king nodded. “And I am s-sorry, Gardener Tradescant, to hear you sympathize with them.” There was a world of warning despite the slight stammer.

“I just hope for peace and that all good men can find a way to peace,” John muttered.

The queen stared at him, affronted by a sudden doubt. “You are my servant,” she said flatly. “There can be no question which side you are on.”

John tried to smile. “I didn’t know we were taking sides.”

“Oh yes,” the king said bitterly. “We are certainly t-taking sides. And I have paid you a w-wage for years, and you have worked in my h-household, or in the household of my dear D-Duke since you were a boy – have you not? And your f-father worked all his life for my advisers and servants, and my f-father’s advisers and servants. You have eaten our b-bread since you were weaned. Which side are you on?”

John swallowed to ease the tightness in his throat. “I am for the good of the country, and for peace, and for you to enjoy what is your own, Your Majesty,” he said.

“What has always b-been mine own,” the king prompted.

“Of course,” John agreed.

The queen suddenly smiled. “But this is my dear Gardener Tradescant!” she said lightly. “Of course he is for us. You would be first into battle with your little hoe, wouldn’t you?”

John tried to smile and bowed rather than reply.

The queen put her hand on his arm. “And we never betray those who follow us,” she said sweetly. “We are bound to you as you are bound to us and we would never betray a faithful servant.” She nodded at the king as if inviting him to learn a lesson. “When a man is ready to promise himself to us he finds in us a loyal master.”

The king smiled at his wife and the gardener. “Of course,” he said. “From the highest servant to the l-lowest, I do not forget either loyalty or treachery. And I reward b-both.”

Summer 1641

John remembered that promise on the day that the Earl of Strafford was taken to the Tower of London and thrown into the traitors’ prison to be executed when the king signed the Act of Attainder – his death warrant.

The king had sworn to Strafford that he would never betray him. He had written him a note and gave him the word of a king that Strafford would never suffer “in life, honor or fortune” for his service – those were his exact words. The most cautious and wily members of the Privy Council fled the country when they recognized that Parliament was attacking the Privy Council rather than attacking the king. Most of them were quick to realize too that whatever the king might promise, he would not raise one hand to save a trusted servant from dying for his cause. But the Bishop of Ely and Archbishop William Laud were too slow, or too trusting. They too were imprisoned for plotting against the safety of the kingdom, alongside their ally Strafford in the Tower.

For all of the long spring months, Parliament had met on Strafford’s case and heard that he had recommended bringing in an army of Irish Papist troops to reduce “this kingdom.” If the king had interrupted the trial to insist that Strafford was referring to the kingdom of Scotland he might have saved him then from the executioner. But he did not. The king stayed silent in the little anteroom where he sat and listened to the trial. He did not insist. He offered, rather feebly, to never take Strafford’s advice again as long as the old man lived if they would but spare his life. The Houses of Parliament said they could not spare his life. The king struggled with his conscience for a short, painful time, and then signed the warrant for Strafford’s execution.

“He sent little Prince Charles to ask them for mercy,” Hester said in blank astonishment to John as she came back from Lambeth in May with a wagon full of shopping and a head full of news. “That poor little boy, only ten years old, and the king sent him down to Westminster to go before the whole Parliament and plead for the Earl’s life. And then they refused him! What a thing to do to a child! He’s going to think all his life that it was his fault that the Earl went to his death!”

“Whereas it is the king’s,” John said simply. “He could have denied that Strafford had ever advised him. He could have borne witness for him. He could have taken the decision on his own shoulders. But he let Strafford take the blame for him. And now he will let Strafford die for him.”

“He’s to be executed on Tuesday,” Hester said. “The market women are closing their stalls for the day and going up to Tower Hill to see his head taken off. And the apprentices are taking a free day, an extra May Day.”

John shook his head. “So much for the king’s loyalty. These are bad days for his servants. What’s the word on Archbishop Laud?”

“Still in the Tower,” Hester said. She rose to her feet and took hold of the side of the wagon to clamber down but John reached out his arms and lifted her down. She hesitated for a moment at the strangeness of his touch. It was nearly an embrace, his hands on her waist, their heads close together. Then he released her and moved to the back of the wagon.

“You’ve bought enough for a siege!” he exclaimed, and then, as his own words sunk in, he turned to her. “Why have you bought so much?”

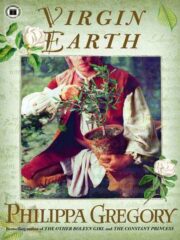

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.