“I have a right to speak to my God in my own way!” John insisted stubbornly. “I don’t need to recite by rote, I am not a child. I don’t need a priest to dictate my prayers. I certainly don’t need a bishop puffed up with pride and wealth to tell me what I think. I can speak to God direct when I am planting His seeds in the garden and picking His fruit from His trees. And He speaks to me then. And I honor Him then.

“I use the prayer book well enough – but I don’t believe that those are the only words that God hears. And I don’t believe that the only men God attends are bishops wrapped up in surplices, and I don’t believe that God made Charles king, and that service to the king is one and the same as service to God. And Jane-” He broke off, suddenly aware that he should not speak to his new wife of his constant continuing love for her predecessor.

“Go on,” Hester said.

“Jane’s faith never wavered, not even when she was dying in pain,” John said. “She would never have denied her belief that God spoke simple and clear to her and she could speak to Him. She would have died for that belief, if she had been called to do so. And for her sake, if for nothing else, I will not deny my faith.”

“And what about her children?” Hester asked. “D’you think she would want you to die for her faith and leave her children orphans?”

John checked. “It won’t come to that.”

“When I was at Oatlands only six months ago, the talk was all about each man’s faith and how far each man would go. If the king insists on the Scots following the prayer book he is bound to insist on it in England too. If he goes to war with the Scots to make them do as he bids, and some say he might do that, who can doubt that he will do the same in England?”

John shook his head. “This is nothing,” he said. “Nonsense and heartache about nothing.”

“It is not nothing. I am warning you,” Hester said steadily. “No one knows how far the king will go when he has to protect the queen and her faith, and to conceal his own backsliding toward popery. No one knows how far he will go to make everyone conform to the same church. He has taken it into his head that one church will make one nation, and that he can hold one nation in the palm of his hand and govern without a word to anyone. If you insist on your faith at the same time as the king is insisting on his, you cannot say what trouble you might be running toward.”

John thought for a moment and then he nodded. “You may be right,” he said reluctantly. “You are a powerfully cautious woman, Hester.”

“You have given me a task and I shall do it,” she said, unsmiling. “You have given me the task of bringing up your children and being a wife to you. I have no wish to be a widow. I have no wish to bring up orphans.”

“But I will not compromise my faith,” he warned her.

“Just don’t flaunt it.”

The horse was ready. John tied his cape tightly at the neck and set his hat on his head. He paused; he did not know how he should say farewell to this new, common sense wife of his. To his surprise she put out her hand, as a man would do, and shook his hand as if she were his friend.

John felt oddly warmed by the frankness of the gesture. He smiled at her, led the horse over to the mounting block and got up into the saddle.

“I don’t know what state the gardens will be in,” he remarked.

“For sure, they will appoint you in your father’s place when you are back at court,” Hester said. “It was only your absence which made them delay. It is out of sight, at once forgotten with them. When you return they will insist on your service again.”

He nodded. “I hope they have not mistook my orders while I was gone. If you leave a garden for a season it slips back a year.”

Hester stepped forward and patted the horse’s neck. “The children will miss you,” she said. “May I tell them when you will be home?”

“By November,” he promised.

She stepped back from the horse’s head and let him go. He smiled at her as he passed out of the stable yard and ’round the path which led to the gate. As he rode out he had a sudden sense of joyful freedom – that he could ride away from his home or ride back to it and that everything would be managed without him. This was his father’s last gift to him – his father who had also married a woman who could manage well in his absence. John turned in his saddle and waved at Hester who was still standing at the corner of the yard where she could look after him.

John waved his whip and turned the horse toward Lambeth and the ferry. Hester watched him go and then turned back to the house.

The court was due at Oatlands in late October, so John was busy as soon as he arrived planting and preparing the courts that were enclosed by the royal apartments. The knot gardens always looked well in winter, the sharp geometric shapes of the low box hedging looked wonderful thinned and whitened by frost. In the fountain court John kept the water flowing at the slowest speed so that there would be a chance for it to make icicles and ice cascades in the colder nights. The herbs still looked well, the angelica and sage went into white lace when the frost touched their feathery fronds behind the severe hedging. Against the walls of the king’s court John was training one of his new plants introduced from the Ark: his Virginian winter-flowering jasmine. On warm days its scent drifted up to the open windows above, and its color made a splash of rich pink light in the gray and white and black garden.

The queen’s orangery was like a jungle, packed tight with the tender plants which would not survive an English winter. Some of the more handsome shrubs and small trees were planted in containers with loops for carrying poles, and John’s men lifted them out to the queen’s garden at first light, and brought them in again at dusk so that even in winter she would always have something pretty to see from her windows. John placed a lemon and an orange tree, both trained into handsome balls, on either side of the door to her apartments, like aromatic sentries.

“These are pretty,” she said to him from her window one day as he was supervising the careful placing of some little trees in the garden below.

“I beg your pardon, Your Majesty,” John said, pulling off his hat, recognizing the heavily accented voice of Queen Henrietta Maria at once. “They should have been in their places before you looked out.”

“I woke very early, I could not sleep,” she said. “My husband is worried and so I am sleepless too.”

John bowed.

“People do not understand how hard it is sometimes for us. They see the palaces and the carriages and they think that our lives are given up to pleasure. But it is all worry.”

John bowed again.

“You understand, don’t you?” she asked, leaning out and speaking clearly so that he could hear her in the garden below. “When you make my gardens so beautiful for me, you know that they are a respite for me and the king when we are exhausted by our anxieties and by our struggle to bring this country to be a great kingdom.”

John hesitated. Obviously it would be impolite to say that his interest in the beauty of the gardens would have been the same whether she was an idle vain Papist – as he believed – or whether she was a woman devoted to her husband and her duty. He remembered Hester’s advice and bowed once more.

“I so want to be a good queen,” she said.

“No one prays for anything else,” John said cautiously.

“Do you think they pray for me?”

“They have to, it’s in the prayer book. They are ordered to pray for you twice every Sunday.”

“But in their hearts?”

John dipped his head. “How could I say, Your Majesty? All I know are plants and trees. I can’t see inside men’s hearts.”

“I like to think that you can give me a glimpse of what common men are thinking. I am surrounded by people who tell me what they think I would like to hear. But you would not lie to me, would you, Gardener Tradescant?”

John shook his head. “I would not lie,” he said.

“So tell me, is everyone against the Scots? Does everyone see that the Scots must do what the king wishes and sign the king’s covenant, and use the prayer book that we give them?”

John, on one knee, on cold ground, cursed the day that the queen had taken a fancy to him, and reflected on the wisdom of his wife who had warned him to avoid this conversation at all costs.

“They know that it is the king’s wish,” he said tactfully. “There is not a man or woman or child in the country who does not know that it is the king’s wish.”

“Then it should need nothing more!” she exclaimed. “Is he the king or not?”

“Of course he is.”

“Then his wish should be a command to everyone. If they think any different from him they are traitors.”

John thought intently of Hester and said nothing. “I pray for peace, God knows,” he said honestly enough.

“And so do I,” said the queen. “Would you like to pray with me, Gardener Tradescant? I allow my favorite servants to use my chapel. I am going to Mass now.”

John forced himself not to fling away from her and from her dangerous ungodly Papistry. To invite an Englishman to attend Mass was a crime punishable by death. The laws against Roman Catholics were very clear and very brutal, and clearly, visibly, flouted by the king and queen in their own court.

“I am all dirty, Your Majesty.” John showed her his earth-stained hands and kept his voice level though he was filled with rage at her casual flouting of the law, and deeply shocked that she should think he would accept such an invitation to idolatory and hell. “I could not come to your chapel.”

“Another time, then.” She smiled at him, pleased with his humility, and with her own graciousness. She had no idea that he was within an inch of storming from the garden in a blaze of righteous rage. To John, a Roman Catholic chapel was akin to the doors of hell, and a Papist queen was one step to damnation. She had tried to tempt him to deny his faith. She had tried to tempt him to the worst sin in the world – idolatory, worshipping graven images, denying the word of God. She was a woman steeped in sin and she had tried to drag him down.

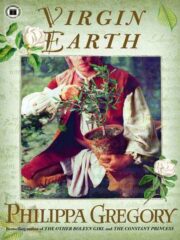

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.