“I’m sorry,” J said. “I didn’t know.”

“I thought you would bring us one home from Virginia, with other things in the cart,” she said childishly.

J thought for a moment of the girl, only a few years older than this one, thanked his luck that he had not been so misled as to bring her back here and burden himself with her care as well as that of his children. “There’s no one in that country who could be a mother to you,” he said shortly. “No one who could be a wife to me here.”

Frances blinked back her tears and looked up at him. “But we need one. A mother who knows what to do when Baby John is naughty, and teaches him his letters.”

“Yes,” J said. “I see we do.”

“Hester says breakfast is ready,” she said.

“Is Baby John at breakfast?”

“Yes,” she answered. “Come.”

J took her hand and led her from the room. Her hand was cool and soft, her fingers were long and her palm had lost its baby fatness. It was the hand of an adult in miniature, not the soft plumpness of a little child.

“You’ve grown,” he observed.

She peeped up a little smile at him. “My uncle Alexander Norman says that I will soon be a proper young lady,” she said with satisfaction. “But I tell him that I shall be the king’s gardener.”

“You still want that?” J asked. She nodded and opened the door to the kitchen.

They were all waiting for him at their places around the dark wooden table: the gardener and the two lads, the cook and the maid and the boy who worked in the house and the stables. Hester was at the foot of the table with Baby John beside her, still half asleep, his drowsy eyes barely showing above the table top. J drank in the sight of him: the beloved boy, the Tradescant heir.

“Oh, Father!” Baby John said, mildly surprised.

J lifted him up, held him close, inhaled the sweet warm smell of sleepy child, hugged him tight and felt his heart turn over with tenderness for his boy, for Jane’s boy.

They waited for him to sit before they took their own places on the benches around the table and then Hester bowed her head and said grace in the simple words approved by the church of Archbishop Laud. For a moment it struck a discord with J – who had spent his married life in the fierce independent certainties of his wife and listening to her powerful extempore prayers – but then he bowed his head and heard the rhythm and the simple comfort of the language.

He looked up before Hester said “Amen.” The household was around the table in neat order, his two children were either side of Hester, their faces washed, their clothes tidy. A solid meal was laid on the table but there was nothing rich or ostentatious or wasteful. And – it was this which decided him – on the windowsill there was a bowl of indigo and white bluebells which someone had taken the trouble to uproot and transplant from the orchard for the pleasure of their bright color and their sweet, light smell.

No one but J’s father, John Tradescant, had ever brought flowers into the kitchen or the house for pleasure. Flowers were part of the work of the house: reared in the orangery, blooming in the garden, shown in the rarities room, preserved in sugar or painted and sketched. But Hester had a love of flowers that reminded him of his father, and made him think, as he saw her seated between his children, and with flowers on the windowsill, that the great aching gaps in his life where his wife and his father had once been might be resolved if this woman would live here and work alongside him.

J could not take his young children from their home to Virginia, he could not imagine that he might be able to go back there himself. His time in the forest seemed like a dream, like something which had happened to another man, a free man, a new man in the new land. In the months that followed, busy anxious months, in which John the Younger had to become John Tradescant, the only John Tradescant, he hardly thought of Suckahanna and his promise to return. It seemed like a game he had played, a fancy, not a real plan at all. Back in Lambeth, in the old world, the old life closed around him and he thought that his father was probably right – as he generally was – and that he would need Hester to run the business and the house.

He decided that he would ask her to stay. He knew that he would never ask her to love him.

J did not formally propose marriage to Hester until the end of the summer. For the first months he could think of nothing but clearing the debts caused by the crash of the tulip market. The Tradescants, father and son, had invested the family fortune in buying rare tulip bulbs, certain that the market was on the rise. But by the time the tulips had flowered and spawned more bulbs under their perfect soil in their porcelain pots the market had crashed. J and his father were left with nearly a thousand pounds owed to their shareholders, and bound by their sense of honor to repay. By selling the new Virginia plants at a handsome profit and by ensuring that everyone knew of his new maidenhair fern, an exquisite variety which everyone desired on sight, J doubled and redoubled the business for the nursery garden, and started to drag the family back into profit.

The maidenhair fern was not the only booty that visitors to the garden sought. John offered them new jasmine, the like of which no one had ever seen before, which would climb and twist itself ’round a pole as rampant as a honeysuckle, smelling as sweet, but flowering in a bright primrose yellow. A new columbine, an American columbine, and best of all of the surviving saplings: a plane tree, an American plane tree, which John thought might grow as big as an oak in the temperate climate of England. He had no more than half a dozen of each, he would sell nothing. He took orders with cash deposits and promised to deliver seedlings as soon as they were propagated. The American maple which he brought back with such care did not thrive in the Lambeth garden though John hung over it like a new mother; and he lost also the only specimen he had of a tulip tree, and nearly came to blows with his father’s friend the famous plantsman, John Parkinson, when he tried to describe the glory of the tree growing in the American wood, which was nothing but a drying stick in the garden in Lambeth.

“I tell you it is as big as an oak with great greasy green leaves and a flower as big as your head!” John swore.

“Aye,” Parkinson retorted. “The fish that get away are always the biggest.”

Alexander Norman, John’s brother-in-law and an executor of John Tradescant’s will, took over some of the Tradescant debts on easy terms as a favor to the young family. “For Frances’s dowry,” he said. “She’s such a pretty maid.”

J sold some fields that his father had owned in Kent and cleared most of the rest of the debts. Those still outstanding came to two hundred pounds – the very sum of Hester’s dowry. With his account books before him one day, he found he was thinking that Hester’s dowry could be his for the asking, and the Tradescant accounts could show a clear profit once more. On that unromantic thought he put down his pen and went to find her.

He had watched her throughout the summer, when she knew she was doubly on trial: tested whether she was good enough for the Tradescant name, and how she matched up to Jane. She never showed a flicker of nervousness. He observed her dealing with the visitors to the rarities. She showed the exhibits with a quiet pride; as if she were glad to be part of a house that contained such marvels, but without boastfulness. She had learned her way around the busy room quicker than anyone could have expected, and she could move from cabinet to wall hanging, ordering, showing, discussing, with fluid confidence. Her training at court meant that she could be on easy terms with all sorts of people. Her artistic background made her confident around objects of beauty.

She was good with the visitors. She asked them for their money at the door without embarrassment, and then showed them into the room. She did not force herself on them as a guide; she always waited until they explained if they had a special interest. If they wanted to draw or paint an exhibit she was quick to provide a table close to the grand Venetian windows in the best light, and then she had the tact to leave them alone. If they were merely the very many curious visitors who wanted to spend the morning at the museum and afterward boast to their friends that they had seen everything there was to see in London – the lions at the Tower, the king’s own rooms at Whitehall, the exhibits at Tradescant’s Ark – she made a point of showing them the extraordinary things, the mermaid, the flightless bird, the whale’s mouth, the unicorn’s skeleton, which they would describe all the way home – and everyone who heard them talk became a potential customer.

She guided them smoothly to the gardens when they had finished in the rarities room, and took care that she knew the names of the plants. She always started at the avenue of chestnut trees, and there she always said the same thing:

“And these trees, every single one of them, come from cuttings and nuts taken from Mr. Tradescant’s first ever six trees. He had them first in 1607, thirty-one years ago, and he lived long enough to see them flourish in this beautiful avenue.” The visitors would stand back and look at the slim, strong trees, now green and rich with the summer growth of their spread palmate leaves.

“They are beautiful in leaf with those deep arching branches, but the flowers are as beautiful as a bouquet of apple blossom. I saw them forced to flower in early spring and they scented the room like a light daffodil scent, a delicious scent as sweet as lilies.”

“Who forced the chestnuts for you? My father?” J asked her when some visitors had spent a small fortune on seedlings and departed, their wagon loaded with little pots.

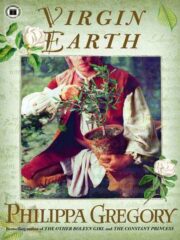

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.