Lambert scowled for a moment at John, hardly seeing him. “I am much at home,” he agreed. “As it turns out, I have little choice. There’s no place for me at Westminster, it seems. And no place for me with my regiment. It’s been given to Lord Fauconberg.”

“Your regiment?” John asked.

Lambert nodded, scowling.

“Who is Lord Fauconberg? I’ve never heard of him.”

“A noble lord. A royalist who has become Cromwell’s man. I think my regiment is his dowry,” Lambert said wryly. “He’s to marry Oliver’s daughter Mary. Quite a little dynasty that Cromwell is making, isn’t it? And with a man who was a royalist, and would be a royalist again, especially if his father-in-law was to be king.”

“I never thought he could govern without you,” John volunteered. “I never thought he would turn against the army.”

“He’s become nervous,” Lambert explained. “He doesn’t want a parliament full of new ideas, he doesn’t want an army that might argue with him. So he dissolved Parliament and took my regiment away from me.”

“Could you not have objected?” John asked. “Surely you command more influence than him, especially in the army.”

Lambert gave a rueful smile. “And do what?” he asked. “Lead them out to fight him? Another war fought over the same ground with the same men? Another half-dozen years of heartbreak? I’m not a man for faction, or division. My task has been to pull the country together, I wouldn’t tear it apart for my own ambitions. I promised that I wouldn’t raise a storm against him if he left my regiment alone, in one piece. I traded: my work and reputation for the integrity of my men. Cromwell agreed. They’re under another man’s command but no good men have been thrown out in the street for thinking for themselves. It was a fair deal, and I have to stick to my side of the contract.”

“I couldn’t believe they were talking of Cromwell for king,” John said. “I thought that we were building a new country here, and now it seems that we were just exchanging one king for another. The family of Stuart for the family of Cromwell.”

“The person doesn’t matter,” Lambert said staunchly. “Nor the name. What matters is the balance. The will of the people in Parliament, the reform of the law so that everyone can get justice, and the limitation of the king – or Lord Protector – or Council of State. It doesn’t matter what the third power is called, but everything has to work in balance. The one with the other. A three-legged stool.”

“But what will you do if the Lord Protector doesn’t want to be in balance?” John asked. “What if he wants the balance tipped all his way? What if the milkmaid on your three-legged stool is thrown down and all the milk spilled?”

Lambert looked at the orange trees in their carrying tubs without really seeing them. “I don’t know,” he said. “We shall have to pray that he has not forgotten so much of what we all once wanted.” His mood suddenly changed and he grinned at John. “But I’m damned if I call him Your Majesty though,” he said cheerfully. “I swear to you, Tradescant, I just couldn’t do it. It would choke me.”

Frances and Alexander stayed at the Ark for the spring. Alexander’s cough was no better and Frances wanted him away from the smell and noise of the city streets.

John woke one night to hear him coughing in their room and heard Frances go quietly down the stairs. He slipped from his own bed, threw his cape around his shoulders over his nightshirt and went downstairs to the kitchen.

Frances was stirring a saucepan over the embers of the fire.

“I’m making a drink of mead and honey for Alexander,” she said. “His cough is so troublesome.”

“I’ll put a drop of rum in it,” John said, and went to fetch the bottle from the cupboard in the dining room. When he came back he saw that Frances had sunk into one of the kitchen chairs with the saucepan left on the hob. He took it off and poured a hearty slug of rum on the mix, and then poured it into a cup.

“Taste it,” he said.

She would have refused but he insisted.

“Very sweet,” she said.

“Take another gulp,” he said. “It’ll put some spirit in you.”

She did as she was ordered and he saw the color come into her cheeks.

“I am sorry,” he said.

She met his eyes frankly. “He’s sixty-seven,” she said bluntly. “We’ve had twelve good years. We never counted on this many.”

John put his hand over hers.

“And you never wanted me to marry him at all,” she said with a flash of residual resentment.

John smiled wryly. “Only to spare you this night,” he said. “And the other nights ahead, while you nurse him.”

She shook her head. “I don’t mind,” she said. “I’m caring for him now, but he has cared for me for as long as I can remember. I quite like being the one in charge for a change. I like repaying the debt of love. He’s always petted me, you know. Petted me so tenderly. I rather like nursing him now.”

John poured a little thimbleful of mead and rum for her. “You sit by the fire for a while and drink this,” he ordered. “I’ll take this up to him.”

Frances nodded and let him go. John took one of the kitchen candles, lit it at the embers of the fire and went quietly up the stairs to Alexander’s bedroom.

Alexander was propped up against the pillow, his breathing hoarse. When he saw John come in he managed a smile of greeting.

“Is Frances all right? I didn’t want her running after me.”

“She’s having a drop of mead and rum at the fireside,” John said. “I thought I’d sit with you for a while, if you wish.”

Alexander nodded. “I brought you this,” John said. “If it doesn’t help you sleep then you have a head stronger than my narwhal tusk.”

Alexander gave a choking little laugh and took a sip of the hot drink. “By God, John, that’s good. What’s in it?”

“Herbs of my own brewing,” John said innocently. “Actually, my Jamaican rum.”

“She’ll have a good settlement,” Alexander said suddenly. “When I go. She’s well provided for.”

“Oh yes?”

“The cooperage will go to my manager, but he’s agreed a price to pay her, and signed a deed. It’s all agreed. She can keep the house if she likes but I thought she’d rather live somewhere else than at the Minories.”

“I’ll look after her,” John said. “It’ll be as she wants.”

“She should marry again,” Alexander said. “A younger man. These are better days now, at last. She can take her pick. She’ll be a wealthy young widow.”

John looked cautiously at him, but Alexander spoke without bitterness.

“I’ll take care of her,” John repeated. “She won’t make a mistake with her choice.” He paused for a moment. “She didn’t make a mistake last time. Though I disagreed at the time. She made no mistake when she chose you.”

Alexander gave a little laugh which turned into a cough. John held his cup till the paroxysm passed and then gave him another sip of the drink. “Kind of you,” he said. “I knew it wasn’t your choice. But it seemed like the best life she could have at the time.”

“I know it,” John admitted. “I know it now.”

The two men sat in companionable silence for a moment.

“All square then?” Alexander asked.

John proffered his hand and gripped Alexander’s own. “All square,” he said fairly.

Summer 1657

Elias Ashmole and the physicians, mathematicians, astronomers, chemists, geographers, herbalists and engineers returned to the Ark to argue, discuss and exchange ideas, on the first Sunday of every summer month. By common accord they avoided the subject of politics. It looked to most men as if Cromwell meant to make himself king. Most of the opposition to him had been dispersed, paid or bullied into silence. General George Monck, another turncoat royalist, held down Scotland for the Lord Protector with a heavy hand and the dour efficiency of the professional soldier. Cromwell’s own son Henry held down Ireland. The Cromwells were becoming a mighty dynasty, and the old idealism was lost in the difficulties of ruling a country where any freedom for the many was feared by the powerful few.

The great fear was not political opposition but religious madness. The men and women who would give their form of worship no name because they wanted it to be everywhere, to be the nature of life itself, were growing in numbers. Their opponents called them Quakers because they shook and trembled in religious ecstasy. Their enemies called them blasphemers, especially after one of their number, James Nayler, entered the city of Bristol like Jesus on a donkey with women throwing down palms before him. The House of Commons had him arraigned for blasphemy and savagely punished; but the mutilating of one individual could not stop a movement which threw up adherents everywhere like poppies in a wheatfield. Very soon John’s visitors banned the discussion of religion too, as overly distracting from the work in hand.

A couple of times Lord Lambert came from his house at Wimbledon to see any new additions to the garden or the rarities room and sometimes stayed for dinner to talk with the other guests. Sometimes men brought curiosities, or things that they had designed or built. Often at these talks Ashmole would lead the discussion, his classical education and his acute mind prompting him to take the part of host in John’s house.

“I don’t like how Mr. Ashmole puts himself forward,” Hester remarked to John as she carried another couple of bottles of wine into the dining room.

“No more than any other man,” he answered.

“He does,” she insisted. “Ever since he catalogued the collection you would think that it was his own. I wish you would remind him that he was nothing more than your assistant. Frances knows her way ’round the collection better than he does. Even I do. And Frances and I kept it safe through three wars, while he was at Oxford living off the richness of the court.”

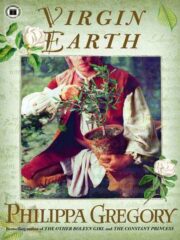

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.