Mary Ashmole, a paying guest for the season, helped herself to a slice of ham. “Young men,” she remarked indulgently.

They could hear Cook laboring up the stairs and then the creak of the floorboards over their heads as she opened Johnnie’s door, and then her coming down the stairs again. Her face when she came into the dining room was bright with mischief. “He’s not there!” she announced, smiling. “And his bed’s not been slept in.”

Hester’s first thought was not of the ale houses of Lambeth, but that he had run away to join Charles Stuart’s court, ridden to the docks and taken a ship to Europe to be with the prince. “Is his horse in the stable?” she asked urgently.

John took one look at her white face and went quickly from the room. Mary Ashmole rose, hesitated.

“Please don’t disturb yourself, Mrs. Ashmole,” Hester said, recovering. “Do finish your breakfast. I expect my son stayed with friends and forgot to send a message.”

She followed John to the stable yard. Caesar’s head was nodding over the stable door. John was questioning the stable lad.

“He didn’t take his horse out last night,” he said to Hester. “No one has seen him since yesterday.”

“Send the boy down to Lambeth and see if he went there,” Hester said.

“This could be much ado for nothing,” John warned her. “If he is drunk under an ale-house table he won’t thank us for sending a search party out.”

She hesitated.

“If he’s not back by midday I’ll go down to Lambeth myself,” John decided.

At midday John took Caesar and rode down to the village but soon came home again. Johnnie had not been in the ale house, and was not staying with any of his friends in the village.

“Perhaps he was walking to Lambeth and had some accident on the road,” Hester suggested.

“He’s not a baby,” John said. “He knows how to fight. And run. Besides, you know Johnnie: he’d always ride rather than walk. If he was going any distance he’d take his horse.”

“If there was a gang of thieves?” Hester suggested. “Or a press gang?”

“The press gang wouldn’t take him, he’s obviously a gentleman,” John said.

“Then where can he be?” Hester demanded.

“You saw him after dinner,” John said. “Did he say anything?”

“He was in his boat,” she said. “He always goes there when he wants to be alone and to think. He knew he was wrong to speak out to Lord Lambert, he promised he would apologize to you and to his lordship. I asked him if he wanted me to stay with him and he said he would come home later.”

She paused. “He said he would come home,” she said. Her voice sounded less and less certain. “He said he would come home when he was merry again.”

John suddenly scowled as if he had been struck by a pang of pain. He crossed the yard and took her hand. “Go and sit with Mary Ashmole,” he ordered.

“Why?”

“I’m just going to have a look round, that’s all.”

“You’re going to the lake,” she said flatly.

“Yes, I am. I’m going to check that the boat is tied up and the oars stowed and then we will know that he rowed ashore and met with some mischance, or changed his mind about coming home.”

“I’ll come too,” she said.

John recognized the impossibility of ordering Hester indoors, started to walk toward the avenue, Hester at his side.

Even in autumn the orchard was too lush for the lake to be seen from the main avenue. Hester and John had to turn away from the chestnut trees to the path that ran westward before they could see the unruffled pewter surface of the water.

It was very quiet. The birds were singing. At the sound of their footsteps a heron rose up from the water’s edge and flapped away with its ungainly legs trailing and its long neck working like a pump handle with each arduous wingbeat. The surface was like a mirror, reflecting the blue sky, untroubled by any movement except the speckling of flies and the occasional plop of a rising fish. The boat floated in the middle of the lake, the oars shipped, its painter trailing in the water tying it to the reflected boat bobbing below.

For a moment Hester thought that Johnnie had fallen asleep in the bottom of the boat, had curled his long legs up inside the little rowing boat and that when they called out his name he would sit up, rub his eyes, and laugh at his folly. But the boat was empty.

John paused for a moment and walked out along the little landing stage and looked down into the water. He could see green weed and the gleam of a brown trout but nothing else. He turned and walked steadily back to the house.

“What are you thinking? What are you doing?” Hester tore her gaze away from the still boat and the peaceful water and went after him. “Where are you going, John?”

“I’m going to get a boat hook and pull the boat in,” he said, without slackening his trudge. “Then I’m going to get a pole and feel for the bottom of the lake. Then I may have to get a net, and then I may have to drain the lake.”

“But why?” she exclaimed. “Why? What are you saying?”

He did not slow, nor turn his head. “Hester, you know why.”

“I don’t,” she insisted.

“Wait for me at the house,” he said. “Go and sit with Mary Ashmole. I will come and tell you as soon as I know.”

“Know what?” she insisted. “Tell me what?”

They had reached the terrace. Mary Ashmole was waiting for them. John looked up at her and she recoiled from the grimness of his face. “Take Hester indoors,” he said firmly. “I will come to her as soon as we know where Johnnie is.”

“You are never going to look for him in the lake,” Hester said. She laughed, an odd, mirthless noise. “You cannot think he fell out of his boat!”

He did not answer her but walked with that same bent-headed trudge round to the stable yard. Hester and Mary heard him shout for the lad and they waited in absolute silence as the two of them walked back down the avenue. John was carrying a long pole, his pruning hook. The lad was carrying a net which they usually used for securing pots in the cart, and a coil of rope.

Mary Ashmole reached out and took Hester’s icy hand. “Be brave, my dear,” she said inadequately.

John marched to the lake as if he were about to undertake a disagreeable but essential garden chore, like hedging or ditching. The garden lad stole one swift glance at his stern profile and said nothing.

John walked to the edge of the landing stage and stretched out with the pruning hook. The blade just reached the painter as it trailed in the water and on the second try he could draw it in toward him.

“Wait here,” he said to the lad, and stepped into the boat. He rowed out toward the middle of the lake and then shipped the oars and peered downward. Gently, with meticulous care, he reversed the pruning hook and lowered it into the water, probing with the handle. When he found nothing he rowed one stroke to the side and repeated the whole process in a widening circle.

The lad, who had been gripped by the horror of this task, found that he was getting bored and started to fidget, but nothing could break John’s intense concentration. He was not thinking of what he might find. He was not even thinking of what he was doing. He just completed each circle and then went a little wider as if it were some kind of spiritual exercise, like a Papist telling her beads, as if it had to be done to ward off some evil. As if it were meaningless in itself, but should be done as a prevention.

Again and again he rowed another stroke and then probed gently into the dark water. In the back of his mind was a thought of how Johnnie was probably already home after a night’s roistering in the City, or a message would soon come from his sister’s house saying that he had decided to make a sudden visit, or he would reappear with an old comrade from the defeated Worcester army. There were so many other explanations more likely than this one that John worked the water of the lake without allowing himself to think what he was doing, divorced from worry, almost enjoying the paddle with the oars and the movement of the wet-handled pole in the water.

When he felt something under the gentle probe of the pole he had a moment of mild regret that now he had to interrupt himself, that now he had a different task to do. Gently, with infinite care, he probed again and felt the object roll and move.

“Bundle of rags,” he whispered to himself, trying to guess at the dimension and weight. “Hidden household goods,” he assured himself.

He turned to look for the stable lad. “Throw me the rope,” he said, his voice steady and unshaken.

The lad, who had slumped on the landing stage, got to his feet and inexpertly tried to throw the rope to John. The first attempt fell in the water and splashed John, and the second attempt slapped him with a wet coil.

“Dolt,” John said and enjoyed the normality of the incompetence of the lad. “Fool.”

He fastened the rope to the ring at the front of the boat. “When I give the word, you gently pull me in,” he ordered.

The lad nodded, and took a grip on the line.

John pulled the pole out of the water and brought up the pruning hook. He took his leather gauntlet from the big pocket of his coat and pulled it over the sharp blade. Then he plunged the pole back into the water with the shielded hook first. It snagged against the object, lost its grip, and then caught.

“Now,” John called to the lad. “But steady.”

The lad was so afraid of doing wrong that he started to pull too lightly. For a moment nothing happened at all, then the little boat started to glide back to the landing stage and John felt the weight of the drowned object on the end of his pole. Gently, smoothly, the boat bobbed toward the landing stage, John gripping the pole and waiting to see the object revealed in the shallow water.

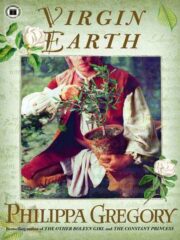

"Virgin Earth" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Virgin Earth". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Virgin Earth" друзьям в соцсетях.